Kansas City Southern history is now appropriate to talk about since the seventh of seven Class I railroads in North America has been approved to merge with Canadian Pacific to make a larger No. 6 Class I railroad.

Kansas City Southern history

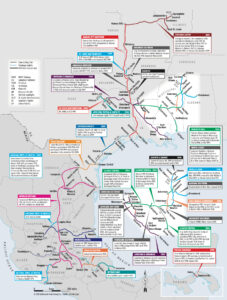

In 1889 Arthur Stilwell began building the Kansas City, Nevada & Fort Smith Railroad (the Nevada being Nevada, Mo.), the earliest antecedent of a trunk line that would one day extend from Kansas City to the Gulf of Mexico. (The railroad’s name was changed to Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gulf in 1892.) Intended to facilitate the export of Midwestern grain, the railroad was built directly south from Kansas City, Mo., creating the shortest route from Kansas City to tidewater. In 1897 its rails reached the Gulf of Mexico at the new city of Port Arthur, Texas—which Stilwell built and named for himself.

The KCP&G fulfilled its purpose. Midwestern farmers saw immediate additional profits, the Kansas City Board of Trade thrived, and new timber stands in Louisiana and East Texas were tapped. But Stilwell was a promoter, not an operating man, and he was unable to cope with the resulting traffic on his lightly-built line. In 1899 the railroad was forced into receivership. Stilwell was ousted (he turned his hand to building the Kansas City, Mexico & Orient Railway) and the KCP&G was reorganized as the Kansas City Southern Railway in 1900. Discovery of the Spindletop oil field in eastern Texas the following year brought more northbound traffic. To build up the railroad, Leonor F. Loree was brought in, and he served as board chairman from 1906 to 1936. (For most of that period he was also president of Delaware & Hudson, explaining, perhaps, the similarity of the steam locomotive rosters of the two railroads. Both railroads were dominated by improbably large Alco-built 2-8-0s, all of them hand-fired, with a sprinkling of Mallet locomotives to assist drag freights over the mountains.)

Modern Kansas City Southern

Today’s KCS also includes two railroads with Louisiana roots. Between 1896 and 1907 William Edenborn built a railroad between New Orleans and Shreveport, La.—the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. In 1923 he extended the line west to McKinney, Texas, within hailing distance of Dallas, by purchasing a Missouri-Kansas-Texas branch. Separately, William Buchanan started a logging railroad in southwestern Arkansas in 1896. By 1906 it was a common carrier: the Louisiana & Arkansas Railway, with a main line from Hope, Ark., south to Alexandria, La., and a short branch from Minden, La., to Shreveport.

Louisiana utility entrepreneur Harvey Couch became interested in railroads in the 1920s, acquiring the L&A and LR&N and consolidating them under the L&A banner. He then turned his attention to Kansas City Southern, acquiring a controlling interest in 1939, and merging L&A into it. For the first time, there was direct, single-line service from Kansas City to New Orleans, and KCS celebrated by christening a new daily streamliner, the Southern Belle. The marketing blitz associated with the train was a powerful statement of brand identity for the reborn KCS, serving notice to shippers and the traveling public that a new option was available. Couch died in 1941, and leadership passed to William N. Deramus Jr., who had risen through the ranks at KCS since hiring on in 1909. Faced immediately with the demands of heavy World War II traffic (Texas crude was still a significant revenue generator, and the KCS service area was replete with military bases), Deramus rebuilt the railroad with heavier rail, new ties, Centralized Traffic Control, and diesel locomotives. He was succeeded in 1961 by his son, William N. Deramus III.

The post-war years were a dark period for much of the industry and for KCS. Over-regulation and publicly subsidized competition were eroding revenue, and with no end in sight, cost containment seemed to be the order of the day. The younger Deramus had previously kept M-K-T and Chicago Great Western afloat with aggressive economy measures, and he did the same at KCS.

Eventually, however, deferred maintenance began to take its toll, and by the late 1960s, KCS was in poor condition. It didn’t help that the railroad’s first-generation diesels were wearing out at the same time, foreshadowing a significant capital spending need for motive power and track maintenance alike. Worse, management’s attention was diverted during this time by a diversification scheme that was intended to cushion the losses from the railroad. Holding company Kansas City Southern Industries eventually owned more than 100 non-rail subsidiaries, while the railroad that had started it all languished.

In late 1972 KCS experienced a rash of derailments and a traffic surge at the same time. Deramus was still focused largely on KCSI, but he tapped Thomas S. Carter, a civil engineer who had served under him at M-K-T, to address the problems at the railroad. Carter was named president in 1973, and he recognized that KCS had two major problems: undermaintained track and midtrain helper locomotives positioned so they were pushing more than pulling. The helper problem was easy to solve; the track required (and got) a $75 million rebuilding program. While the rebuilding was in process, the road landed a contract to move coal to power plants in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas, further justifying reconstruction. Besides an improved physical plant, Carter is also credited with a change in operating philosophy—away from the lengthy, once-daily trains of the Deramus III era, and embracing scheduled operations with shorter trains and more efficient car handling.

In late 1972 KCS experienced a rash of derailments and a traffic surge at the same time. Deramus was still focused largely on KCSI, but he tapped Thomas S. Carter, a civil engineer who had served under him at M-K-T, to address the problems at the railroad. Carter was named president in 1973, and he recognized that KCS had two major problems: undermaintained track and midtrain helper locomotives positioned so they were pushing more than pulling. The helper problem was easy to solve; the track required (and got) a $75 million rebuilding program. While the rebuilding was in process, the road landed a contract to move coal to power plants in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas, further justifying reconstruction. Besides an improved physical plant, Carter is also credited with a change in operating philosophy—away from the lengthy, once-daily trains of the Deramus III era, and embracing scheduled operations with shorter trains and more efficient car handling.

The KCS renaissance of the past 30 years is often reckoned to have started with the 1994 acquisition of MidSouth Rail Corp. This former Illinois Central property provided KCS with a link between its legacy lines at Shreveport and a connection with Norfolk Southern at Meridian, Miss. (MidSouth also had branches to Birmingham, Ala. and central Tennessee.) Ironically, MidSouth was acquired to make KCS more attractive as a takeover candidate.

Haverty years at KCS

Mike Haverty thought he could make a going concern of KCS, however. He was named CEO of the railroad in 1995, following successful stints at the Santa Fe, where he had served as president, and Missouri Pacific. In the mid-1990s, Western railroads were consolidating into two mega-systems, BNSF and Union Pacific, and few believed that KCS could remain independent. But Haverty was an avid student of railroad history, and he understood that KCS had always been a north-south railroad in an east-west world: The way to remain independent was to double-down on that heritage.

Shortly after arriving at KCS, Haverty began discussions that would result in the acquisition of the Northeast rail franchise in Mexico, which had become available for privatization. (Haverty was also aware of Arthur Stilwell’s dream of a railroad to Mexico’s West Coast.) By 2005, KCS and the newly renamed Kansas City Southern de México were a single, integrated railroad, connecting the second-biggest rail center in the U. S. (Kansas City) with Mexico’s principal industrial centers and ports on both of Mexico’s coasts. Cross-border container and automotive traffic represent a significant share of the company’s revenue base.

Also acquired on Haverty’s watch were the Texas Mexican Railway and a former Southern Pacific line in Texas, which together closed the gap between KCS’s legacy U. S. lines and KCSM. KCS also acquired the former Alton Route lines from Kansas City to East St. Louis, Ill. and Springfield, Ill., thus gaining new connections to the east. In addition, KCS holds a 50 percent interest in the Panama Canal Railway, which provides a faster and often less expensive alternative to the Canal for container traffic.

Kansas City Southern, left for dead more than once, is a modern railroad renaissance story.

I wonder with the new merger, how will it affect the KCS line through Oklahoma?