Without an ampersand, directional vector, or superlative in its title, the Lehigh Valley Railroad was of understated geographical reach. Its 440-mile New York-Buffalo line was slightly longer than competing routes of the Erie, New York Central, and Lackawanna, but shorter than the Pennsylvania’s. LV’s earliest component dated to 1836, but “the Valley” owed its existence to Asa Packer, a Connecticut Yankee who’d done well with canals and coal land investments. He got control of the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill & Susquehanna Railroad and renamed it Lehigh Valley in 1851.

Expanding east to compete with Lehigh Coal & Navigation Co.’s canal in hauling anthracite east, LV by 1855 went down its namesake river course from Mauch Chunk (present-day Jim Thorpe) to Easton, Pa. LV also built westward, paralleling LC&N’s Lehigh & Susquehanna Railroad. New coalfield branches assured future business.

LV and L&S both continued north over Penobscot Mountain and into the Susquehanna River valley. The 1.8% descent brought rails into Wilkes-Barre and the northern anthracite region, and LV’s 1865 acquisition of the North Branch Canal provided a water grade northward. Track was laid on the towpath, aiming for the broad-gauge Erie Railroad at Waverly, N.Y.

From Waverly, LV partnered with Erie, opening an extension in 1869 to Elmira employing trackage rights and utilizing a third rail inside Erie’s gauge. Erie hauled LV’s trains to Buffalo until LV extended the third rail there in 1876. Cooperative connections from Philadelphia permitted through passenger service to Buffalo and Niagara Falls.

The Valley is credited with the first 2-8-0 and 2-10-0 locomotives, heavy power for the day necessitated by LV’s grades and growing general freight traffic. LV next built into New York’s Finger Lakes region and connected to the NYC at Geneva. Acquisition of the Southern Central gave entry to Auburn and Fair Haven, N.Y., a Lake Ontario port for Canada-bound coal. The farms and towns of these feeder lines would absorb thousands of carloads of coal and other necessities as agricultural and manufactured products moved in the opposite direction. Prior to all-weather roads and motor vehicles, local rail service was essential for commercial, social, and political intercourse and national cohesion.

Lehigh Valley Railroad had relied on friendly connections east of the Delaware River until the Lackawanna shifted its coal traffic from the Jersey Central to the Morris & Essex, which had also forwarded LV traffic to tidewater. CNJ responded by leasing the L&S, gaining a through route to Wilkes-Barre, so it too, no longer needed the LV. The Valley in turn leased New Jersey’s Morris Canal, primarily for 60 harborside acres in Jersey City. The canal’s circuitous, hilly cross-Jersey route was no railroad right of way, yet it did carry some LV coal east while the railroad wove together its own rails to the Atlantic.

Initially, LV’s New Jersey Division was a linear patchwork of constructed and rented lines and trackage rights, but by 1900 they were amalgamated into a first-rate main line with several terminals. Perth Amboy, on Raritan Bay, became a major coal transshipping facility, and an arrangement with PRR provided entry to Exchange Place Station in Jersey City. LV’s acquisition of National Docks Railway gave access to Constable Hook oil refineries and additional steamship business.

Anticipating its own route to Buffalo, LV acquired property there on Lake Erie. Packer’s goal of an “Ocean to Lakes” railroad became a reality in 1892 when LV finished its own line to Buffalo, but its financial strength was sapped. The imperious Archibald A. McLeod’s Philadelphia & Reading leased the LV that year in an effort to control anthracite mining and transportation. The 1893 financial panic ended McLeod’s scheme, so LV, though still weak financially, was again its own master. Nonetheless, in 1896 the Valley inaugurated the Black Diamond Express, a luxury day train advertised as “The Handsomest Train in the World.”

New leadership, diversification for Lehigh Valley Railroad

In 1897, dissatisfied with LV’s management, the Packer estate turned to J. P. Morgan to protect its investment. Infusing new capital and leadership, Morgan rebuilt the railroad. Scattered facilities were consolidated, and modern locomotives and cars arrived. Increasingly, cement and steel from the Lehigh region, and manufactures and imports from New York and New England were rolling westward as grain, lumber, merchandise, flour, meat, and produce moved east. Anthracite continued to move in both directions, but was no longer LV’s major business.

In 1903, construction began on Sayre Shops, a modern facility named to honor Chief Engineer Robert H. Sayre. LV engines were characterized by the wide Wootten firebox along with the Camelback design, inside-frame trailing trucks, overhanging ash hoppers, and twin sand domes. Wheel arrangements of 0-8-0, 4-6-0, 4-6-2, and 2-8-2 filled the roster; 2-10-2s came later. The early 1900s saw multiple-tracking, stronger bridges, grade realignments, stone ballasting, improved signaling, and increased yard capacity. LV remained competitive as trains became heavier, faster, safer, and more comfortable for the public.

That the Lehigh Valley Railroad was always foremost a freight carrier, though, is reflected in many instances. Lacking its own New York station, LV used PRR’s Jersey City terminal until 1913, then moved to Jersey Central’s down the Hudson at Communipaw. In 1918, by U.S. Railroad Administration edict, LV’s through trains were rerouted to PRR’s Penn Station in New York, although some locals remained on CNJ.

Harbor freight facilities included piers at the former Morris Canal Basin in Jersey City and the National Docks Terminal and Constable Hook pier. A fleet of tugs, barges, carfloats, and lighters moved up and down the Hudson, East, and Harlem rivers, reaching freight houses and connections beyond direct rail service. The early 1900s saw facilities again expanded, a mechanical coal dumper installed, and the new 500-acre Claremont Terminal.

LV was in good condition to meet the crushing requirements of World War I, and soon, freight for the Allies flowed into ports faster than ships could load it. Yards were choked, many holding munitions awaiting transshipment at LV’s Black Tom Island facility. In July 1916, fire and explosions there resulted in $20 million damage extending well beyond the railroad, which alleged German sabotage. The traffic congestion led to creation of the USRA to oversee virtually all U.S. rail operations until 1920.

In 1916, LV built a new Buffalo passenger terminal and acquired property to build Tifft Yard. Federal rulings circa 1920 forced divestiture of LV’s Great Lakes steamship line and coal holdings, though.

The postwar period required another rehabilitation of LV’s plant, rolling stock, and 1,000 locomotives. Included was a new tunnel through Musconetcong Mountain in New Jersey. The Claremont Terminal project cost $26 million, including a 3,500-foot pier that employed narrow-gauge electric shunters. A bridge over Newark Bay, shared with PRR, provided access. Government insistence on greater navigational clearance, however, forced the roads to build a higher span, which required the raising of Oak Island, LV’s main area yard. Despite these expenditures, the Valley was a coveted stock investment, grossing $80 million in 1926.

Familiar ups and downs on the Lehigh Valley Railroad

Internal combustion power came to the Valley in the 1920s with diesel-electric switchers and self-propelled rail cars to meet anti-smoke ordinances. The road studied electrifying over Penobscot Mountain, but the Depression interfered. Although hard hit, LV was in better physical shape than many roads owing to its rebuilding programs.

The horizon was dark, though, as coal earnings continued to fall and highways drained passengers and freight. Trains were discontinued and lines abandoned, but federal aid was needed. These measures, plus stringent economy, reduced bond interest, while extended maturity dates kept bankruptcy at bay. To hold customers, LV improved schedules with new 4-8-2s and 4-8-4s, and its Asa Packer, John Wilkes, and Black Diamond were modernized with upgraded equipment.

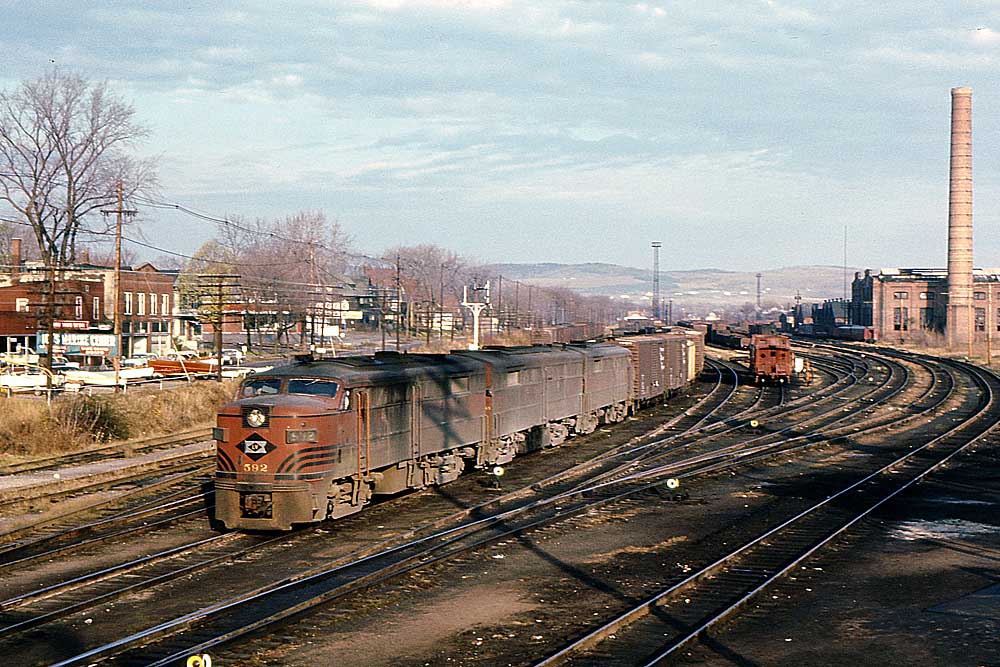

LV’s ocean terminals and proximity to defense facilities made for big demands during World War II. Coordinated, secret movements from bases to seaports ran daily. Enemy submarines forced petroleum shipments to rail, helping boost traffic to a peak 43 million tons in 1944. The next year, LV acquired four FT A-B road diesels, and by fall 1951 it was dieselized, mostly with Alcos and EMD’s, plus some Baldwins. All wore an attractive dark “Cornell” red (for the university in on-line Ithaca) and black scheme.

Two 1951 Budd RDC’s for branchline trains were LV’s only lightweight streamlined passenger equipment. From the 1950s on, LV continually reduced facilities, branches, local service, and mainline trains. Construction of the New York Thruway took down its Buffalo passenger station.

Lehigh Valley last showed a profit in 1956. Industrial development, piggyback and auto-racks, plus run-through service at Buffalo with Nickel Plate, were positive efforts, but insufficient to regain profitability. When LV ended passenger service on Feb. 4, 1961 [see “Mr. Fogg, No. 603, and the Inextinguishable Lehigh Valley,” Winter 2008 Classic Trains], dropping the New York-Toronto (with CN) Maple Leaf, the New York-Lehighton John Wilkes, and its connecting Lehighton-Hazleton RDC, it became only the third Class I railroad (after M&StL and Maine Central) to go freight-only. High terminal costs, confiscatory taxes, wage increases, and higher maintenance expense tightened the downward spiral.

The PRR held nearly one-third of LV stock. Fearing further depreciation of its LV investment, Pennsy got ICC approval for control and by 1962 owned almost 90% of Valley stock, hoping shared terminals would cut expenses. Some PRR diesels were transferred to LV, but no substantive improvement resulted. Additional branchline mileage was cut, and much of the main line was singled-tracked with CTC signaling. More trackage was trimmed in 1965 by instituting a shared arrangement with equally distressed CNJ east of Wilkes-Barre to Allentown.

Lehigh Valley Railroad’s last years featured an odd panoply of diesel color schemes. A “new image” contest resulted in gray-and-yellow Alco C420s, then black-and-white C628s representing the choice of President John Nash. Tuscan red with thin yellow stripes showed PRR’s influence, and a Geep and an Alco RS got wide yellow bands that weren’t repeated. Leased power from Bangor & Aroostook, B&O, Lehigh & Hudson River, and Pittsburg & Shawmut widened the spectrum. The Valley’s last new power, EMD GP38s plus GE U23Bs via federal money, were a delightful surprise in a shiny medium red with a single yellow stripe plus black-and-white safety stripes.

A linchpin for friendships

Beginning about 1960, I would attend meetings of the Lehigh Valley Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society in Allentown, Pa., with friends Richard Taylor and the late George Berisso. We’d leave our New Jersey homes, meet retired railroader John P. Scharle in Allentown, and make a day’s outing along the Valley. Sometimes we’d get to Sayre before heading back for the evening meeting. There might be a stop to visit the Bednars — “Pop,” Mike, Keith, and Danny — in Hokendauqua, just north of Allentown. Their backyard bordered the LV main, and they were the most dedicated of LV’s fans. We often would run into Dave Augsburger and other chapter members along the line. For me, the Lehigh Valley was a catalyst, bringing friends together and creating memories lasting well beyond the railroad’s demise.

In the late 1960s, talks of merger or sale to N&W, C&O, or a Canadian road, or of the Valley becoming part of the pending Penn Central, resulted in nothing of substance. When PC declared bankruptcy June 21, 1970, LV followed three days later and would struggle along while Washington formulated plans to untangle the Northeast rail quagmire. Meantime, Lehigh Valley took over Jersey Central’s operations in Pennsylvania, and joined in a through-freight service between Potomac Yard in northern Virginia and Portland, Maine, with B&O, Reading, Delaware & Hudson, and Boston & Maine. The end was in sight, though, as the trustees set a date for termination of operations. Several infusions of emergency federal money maintained service on LV and five other bankrupts while plans for Conrail were finalized.

On April 1, 1976, just short of its 130th anniversary, Lehigh Valley Railroad’s flag fell, but today, key segments of its main line, especially on the east end, remain vital and busy.

Growing up in Central Jersey, all the anthracite roads were not far away. The Jersey Central was always close and convenient, and was our mode of choice to visit family in Bayonne or travel to New York. But the Lehigh Valley always held a mystique for me. In the evenings or when the wind was right, one could hear their melodious chime horns blow for crossings as the relatively few freights hustled through Piscataway and Middlesex. When my friends and I would ride our bikes to the landmark Model Railroad Shop in Dunellen, the New Market Road crossing was right down the street, and we always hoped to catch something going by while we were there. Not far from there, I saw my first low-nose diesels (the 400-series Alcos) through the woods as they headed westbound along New Market Pond.

The upshot of all the rationalization in the 1970s is that the former LV main is now THE main freight route through New Jersey. Norfolk Southern freights headed to the New York/New Jersey port from anywhere all merge onto the old Lehigh Valley in Allentown, PA to travel through Jersey until they reach Oak Island Yard. As well, most CSX freights heading up the east coast to the Port, but also beyond to New England, ride the old Reading New York Branch as far as Port Reading Junction in Manville, NJ, and then move onto the old LV main for the trip up to Oak Island Yard and the port. Some CSX trains diverge in Jersey City and move onto the old NYC West Shore line to continue to Selkirk Yard (near Albany) and beyond.

The end result is that the old Lehigh Valley between Manville and Newark is probably busier than it’s been sine WW II, to the delight of us Jersey railfans.

Brazil has some dual wide gauge with more standard being built.

Good article–well organized and well written. I never knew much about the LV, but now I feel a little better acquainted. The dual-gauge arrangement with the Erie was interesting–can’t have been very many dual standard-wide gauge installations anywhere!