Although the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway employed several nicknames — “Dixie Line,” “Nashville Road,” and “Lookout Mountain Route” among them — to former employees and their families, it will always be “Grandpa’s Road.”

James A. Skelton was one of those Grandpas. He was 14 in April 1862, and although the War Between the States was still far from Big Shanty, Ga., times were hard for young Jim and his family. He was the oldest of four and doing what he could to help their widowed mother.

A train crew told the youth the railroad was looking to hire a water boy and a yard engine fireman in Cartersville, so about 6 a.m. on April 12, he bought a ticket and boarded the passenger car of a northbound mixed train that had stopped in Big Shanty.

“He saw a passel of strangers walk by,” says Joe Bozeman, 72, Jim’s great-grandson whose family still lives in Big Shanty (now Kennesaw). “He opened a window and watched; it wasn’t uncommon for the fireman and brakeman to do some switching while the rest of the crew was having breakfast in the Lacy Hotel.”

“I heard them uncouple the car, and then they disappeared around the curve,” Skelton later recalled. The locomotive General and three boxcars were gone. People poured out of the hotel, hollering, “They’ve stolen the train!” He was the last living witness of that famous Andrews Raid when he died in 1940.

Young Jim never got a railroad job in Cartersville on what was then the Western & Atlantic. He enlisted in the Georgia militia and was a guard at the POW camp in Andersonville, but he hired on the W&A after the war, retiring in 1903 as a section foreman. Skelton’s father had been a section hand on the railroad, and all but one of Jim’s sons, and many of their sons, worked for the W&A and/or its successor, the NC&StL.

“The thing I always heard was that if you wanted to work for the NC&StL (usually spoken as “N-C-and Saint-L,” or just “NC”), you were either born into it or married into it,” Bozeman says. “Every railroader I ever knew who worked for the road had a relative there — father, grandfather, great-grandfather. I’m not saying that’s always good, but that’s the way it was. There was a lot of dedication to the road; they took care of you, and you were supposed to take care of them.”

Author and historian Mark S. Womack, 93, of Chattanooga, concurs. He signed on as an operator in 1941. “The NC was known as Grandpa’s Road because so many kinfolk worked for it,” says Womack, who was an officer for L&N after the 1957 merger and retired in 1983 as superintendent of rules for L&N’s Family Lines sibling Seaboard Coast Line.

Womack says one of his former bosses, S. P. Strickland, started as an operator on NC’s Atlanta Division and rose to assistant vice president of transportation for L&N. Yet at the NC, even after he’d become an officer, “it wasn’t unusual for a conductor or engineer to call him ‘Strick,’ and he never objected to it. I never heard anything like that on the L&N. There, it was “Mister So-and-So.’ ”

The NC&StL story is of two railroads that came together: the Nashville & Chattanooga, chartered by Tennessee in 1845 to connect its namesake cities, and the Western & Atlantic, created in 1836 and owned to this day by the State of Georgia. J. Edgar Thomson, chief engineer of the Georgia Railroad & Banking Co. and later president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, laid out the N&C main line southeast from Nashville, crossing the Cumberland range, the Tennessee River, Raccoon Mountain, and circling Lookout Mountain into Chattanooga. With a tunnel through Cumberland Mountain and bridges over the Tennessee, the first train went the entire 152 miles on Feb. 11, 1854. Another early line, Southern Railway predecessor Memphis & Charleston, building up the river valley, met N&C at Stevenson, Ala., and used it to enter Chattanooga. To this day CSX and Norfolk Southern share that line from Stevenson to Wauhatchie, Tenn.

W&A built north from an arbitrary spot that one day would be Atlanta. Given the primitive locomotive technology, U.S. Army Lt. Col. Stephen H. Long laid out a line without heavy grades. This meant curves, 10,000 degrees’ worth, the equivalent of 28 circles in 138 miles. After a 1,447-foot tunnel through Chetoogeta Mountain was bored, the first train ran through on May 9, 1850; the tunnel was replaced by a larger one in the 1920s.

Connected, the N&C and W&A comprised an arrow pointing to the heart of the South, which Union forces quickly recognized in 1861 when hostilities with the Confederacy broke out. Union troops captured Nashville in February 1962, and future offensives would be staged there.

“Andrews’ Raiders,” Union soldiers in civilian clothing led by undercover agent James J. Andrews, infiltrated Georgia and stole the General at Big Shanty. Their objective was to lift rails and burn bridges to cut off Chattanooga. Their mission failed, the raiders were captured, and Andrews and seven of his men were hanged as spies; the others escaped or were exchanged. Chattanooga held out until September 1863. (The raiders were the first recipients of the U.S. Medal of Honor for military valor, and their story inspired the 1956 Walt Disney movie, The Great Locomotive Chase.) The Union Army drove down the N&C to Chattanooga and the W&A to Atlanta, which fell in September 1864.

Enter the L&N

In 1870 N&C leased the Nashville & Northwestern, extending it 168 miles to the Mississippi River at Hickman, Ky., and two years later bought it, soon renaming the combined lines Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis. President Edmund W. Cole sought an extension to St. Louis, but that did not happen.

Cole also hoped to assume the W&A lease held by his friend, former Georgia Gov. Joseph E. Brown, allowing him to reach Atlanta. Archrival Louisville & Nashville, though, had seen enough. In 1880 it got stock control of the NC and ousted Cole, so it would be the Louisville-based “Old Reliable,” not the Nashville Road, doing the empire-building. L&N allowed NC to operate separately, but Louisville would call the shots.

NC&StL did get to the Ohio River, at Paducah, Ky., mouth of the Tennessee River, when L&N bought the Paducah, Tennessee & Alabama and the Tennessee Midland from foreclosure and in 1896 directed subsidiary NC to lease them. The two formed a 254-mile semicircle from Memphis east and north, crossing NC’s Nashville Division at Bruceton, Tenn. On the south end, the new Paducah & Memphis Division gave NC direct access to Memphis, and at Paducah, a connection with the Burlington Route. NC and the Burlington built a bridge over the Ohio at nearby Metropolis, Ill., which opened on Jan. 1, 1918. Six years later Illinois Central bought in to extend its Edgewood Cutoff freight line.

Atlanta was attained by NC&StL in 1890 when the W&A lease came up for renewal and, with some bid-rigging, NC was the winning suitor. The original N&C became the Chattanooga Division and W&A the Atlanta Division.

Historian Richard E. Prince cites the Tennessee Centennial Exposition of 1897 in Nashville as a logical dividing point in NC&StL history. From its founding before the Civil War, it was building, expanding, and acquiring, achieving a peak of 1,259 route-miles. Afterward came 60 years of better locomotives and rolling stock, and capital improvements.

NC’s main lines connected Memphis, Nashville, and Atlanta. Secondary lines reached Paducah and Hickman, Ky., plus Huntsville and Gadsden, Ala. A half dozen branches into the Tennessee hills brought out timber, phosphate, limestone, coal, and iron, and farther south, cotton. NC developed traffic and industries, modernized its fleet of steam locomotives, and with L&N and other roads, helped tap the booming Florida tourist trade with the Midwest-Florida “Dixie” trains Dixie Flyer, Dixie Limited, and Dixie Flagler, plus the 1946 St. Louis- (later Chicago-) Atlanta streamliner Georgian.

The road had its share of unique items and was a pioneer. Historian Dain L. Schult says NC was the only southern road to try a Camelback and a duplex; neither type worked out. It tried radio dispatching in the 1920s, and in 1930 was the first Southeast road to acquire 4-8-4s, which it called the Dixie type. In 1947, it outshopped its own streamliner, the City of Memphis, a handsome train of updated heavyweights led by a shrouded 4-6-2.

The NC had a pusher base in Cowan, Tenn., for Cumberland Mountain’s 2.5 percent ruling grade and curves of 5 to 6½ degrees. The summit is inside a 2,228-foot tunnel. At the north portal, the branch to Tracy City and Palmer crossed over the main on a stone arch bridge, the site of many publicity photos. The branch was abandoned in the 1980s, but the bridge remains, although it’s on private property that is patrolled.

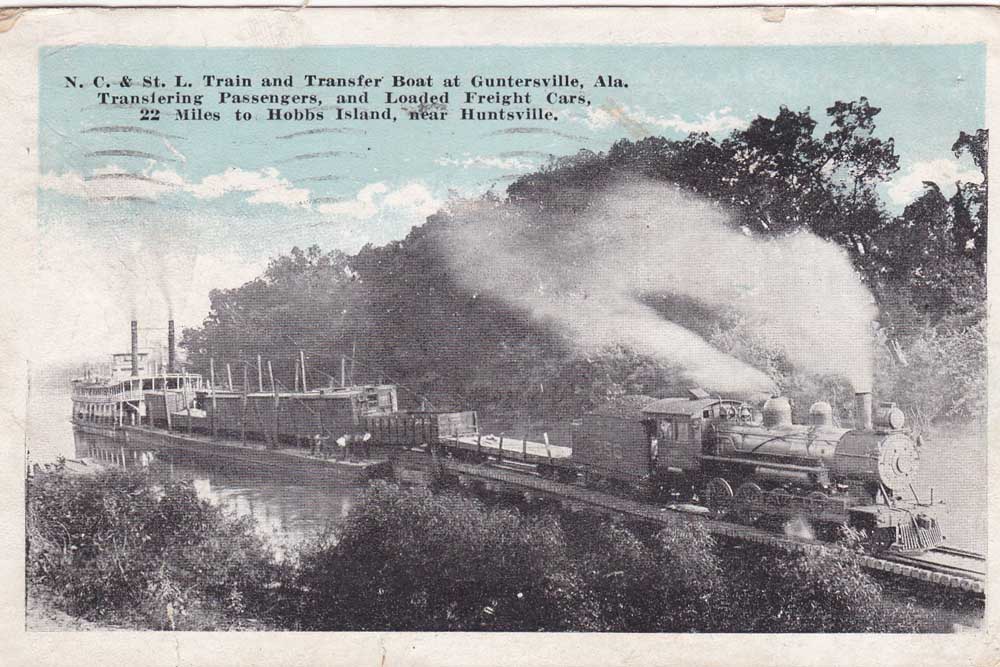

Although NC&StL was far from an ocean or a big lake, it maintained a long water transfer. In 1893 NC found itself with a segment, Guntersville to Gadsden, Ala., “orphaned” from the rest of the system so it figured a tow boat and carfloat moving 22 miles on the Tennessee River between Hobbs Island, south of Huntsville, and Guntersville would be cheaper than building a bridge and more railroad. This “NC&StL Navy” shuttled cars up and down the river until 1960.

“It was a wonderful little family railroad,” confirms Mary Elizabeth Chambliss, 86, of Jackson, Tenn. She joined NC&StL as a 17-year-old operator in 1948 and retired from CSX in 1988. “Everybody was related; it was a small railroad, and everyone wanted it to be the best.” On the other hand, she says, “You’d have to be careful what you said about someone, because he’d be related to someone else on the railroad.”

Chambliss, naturally, is family. She learned the craft from her father Robert Bracken, an operator in Jackson.

Prosperity, decline, merger

Coal mined on-line was an important commodity, and assorted industries had arisen: cement-making in Cowan; steam boiler fabrication in Chattanooga; and steel pipe production in Gadsden. Few knew it then, but owing to resource depletion, environmental regulation, advancing technology, and overseas competition, this traffic became endangered and, in a generation, or so was gone. Ditto passenger traffic, as on most railroads.

By the mid-1950s, an era of railroad mergers was at hand, and after four late-1940s absorptions (Alton, Moffat Road, Pere Marquette, Wheeling & Lake Erie), NC&StL was the next to go. On Aug. 30, 1957, after 77 years of tolerating it as a semi-autonomous entity, L&N merged the NC out of existence. The former NC branches would go, some abandoned, and some sold to short lines. The Paducah Gateway is history, but the Memphis-Nashville-Chattanooga-Atlanta trunk remains, though part of the west end is on ex-L&N trackage.

L&N not only adopted “The Dixie Line” as its own slogan, but it also thoroughly purged the NC&StL from corporate memory. NC being “family,” though, is why the return to steam of No. 576, a 1942 class J3 “Yellow Jacket” 4-8-4 previously on display in Nashville’s Centennial Park since 1953, generates excitement in NC territory. It acknowledges the memory of something long gone, but cherished.

“Connected, the N&C and W&A comprised an arrow pointing to the heart of the South, which Union forces quickly recognized in 1861 when hostilities with the Confederacy broke out. Union troops captured Nashville in February 1962, and future offensives would be staged there.”

I always knew those Yankees were lousy fightin’ soldiers. But I sure never realized it took them a full 100 years to capture Nashville!

Rosemary Entringer would have caught that date trouble, your comment is great nonetheless!!

The late Col. Bogle was also an NC&St L historian and Locomotive chase expert. His father had been a dispatcher in Cowan. Col. Bogle rescued several of the marble mile markers from Dalton GA, including one near where the chase ended, I believe. . The Family Lines had pulled them up and piled them in Dalton when they replaced them. Which was better than knocking them over, I guess. Wonder what happened to that pile of markers.

COL. Bogle was a fine southern gentleman and historian it was always enligthing to hear him talk, He is missed!