Penn Central history began existence on Feb. 1, 1968. More accurately, it was incorporated in 1846 as the Pennsylvania Railroad; changed its name to Pennsylvania New York Central Transportation Co. on Feb. 1, 1968, when it merged the New York Central; and adopted the name Penn Central Co. on May 8, 1968. On Oct. 1, 1969, it again changed its name, to Penn Central Transportation Co., and became a wholly owned subsidiary of a new Penn Central Co., a holding company.

The stockholders of the Pennsylvania and the New York Central approved merger of the two roads on May 8, 1962; nearly four years later the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the merger on the following conditions:

- The new company (“Penn Central” for convenience) had to take over the freight and passenger operations of the New York, New Haven & Hartford. That happened on Dec. 31, 1968.

- Penn Central had to absorb the New York, Susquehanna & Western. PC and the Susquehanna could not agree on price, and NYS&W became part of the Delaware Otsego System.

- Penn Central had to make the Lehigh Valley available for merger by either Norfolk & Western or Chesapeake & Ohio or, if neither of those roads wanted it, merge it into PC. Lehigh Valley struggled along on its own and entered bankruptcy only three days after Penn Central did.

The beginnings of failure

The merger was not a success. Little thought had been given to unifying the two railroads, which had long been intense rivals with different styles of operation. In the previous decade New York Central had trimmed its physical plant and assembled a young, eager management group under the leadership of Alfred E. Perlman. The Pennsy was a more conservative and traditional operation. Many of NYC’s management people (the “green team”) saw that Pennsy (the “red team”) was dominant in Penn Central management and soon left for other jobs.

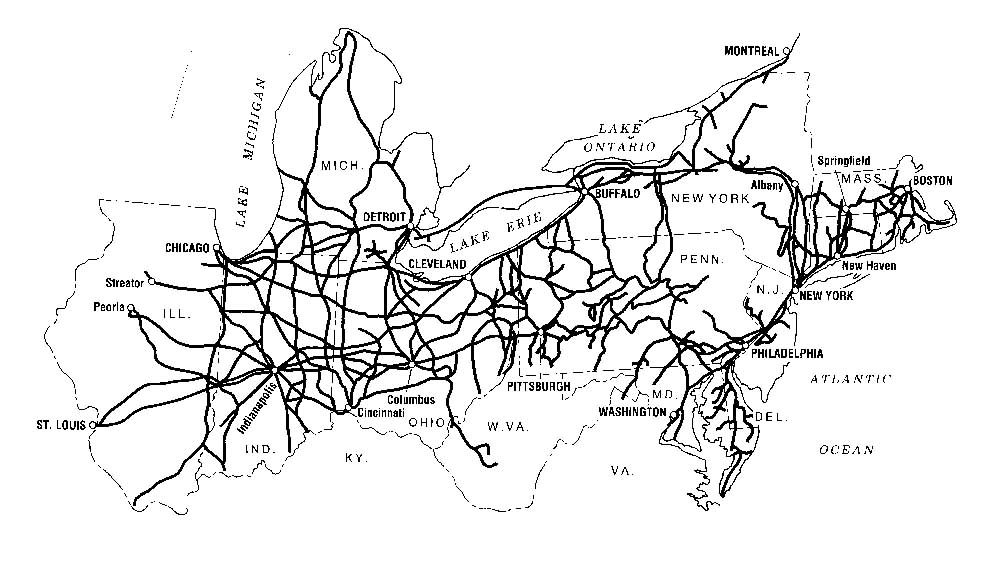

In addition to the problems of unification, the industrial states of the Northeast and Midwest were fast becoming the “Rust Bowl.” As industries shut down and moved away, railroads found themselves with excess capacity. The Pennsylvania was worse than practically anyone else in having four or six tracks where one or two would do — tracks that were no longer needed but were still on the tax rolls. West of the Alleghenies, Pennsy and Central duplicated each other’s track nearly everywhere. The PC merger was like a late-in-life marriage to which each partner brings a house, a summer cottage, two cars, and several complete sets of china and glassware — plus car payments and mortgages on the houses.

Bankruptcy and reorganization in Penn Central history

Pennsy and New York Central came into the merger in the black, but Penn Central’s first year of operation yielded a deficit of $2.8 million. In 1969 the deficit was nearly $83 million. PC’s net income for 1970 was a deficit of $325.8 million. By then the railroad had entered bankruptcy proceedings—specifically on June 21, 1970. The nation’s sixth largest corporation had become the nation’s largest bankruptcy.

The reorganization court decided in May 1974 that PC was not reorganizable on the basis of income. A U. S. government corporation, the United States Railway Association, was formed under the provisions of the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 to develop a plan to save Penn Central. The outcome was that Consolidated Rail Corporation, owned by the U. S. government, took over the railroad properties and operations of Penn Central and six other railroads — Central of New Jersey, Erie Lackawanna, Lehigh Valley, Reading, Lehigh & Hudson River, and Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines — on April 1, 1976.

It was a major step toward nationalization of the railroads of the U. S. They had been nationalized briefly during World War I(through the agency of another USRA, the United States Railroad Administration), but the U. S. had held out against a world-wide trend toward nationalization of railroads until the creation of Amtrak, which nationalized the country’s passenger trains, on May 1, 1971.

Metroliner and TurboTrain

PC participated in two passenger service experiments in cooperation with the U. S. Department of Transportation. Both were aimed at upgrading passenger service in the Northeast Corridor. Between New York and Washington PC inherited the Metroliner experiment that the Pennsy had begun—fast electric trains that were intended for a maximum speed of 160 mph. The inauguration of service was delayed several times, and when it did begin, it was not shown in The Official Guide. While not an absolute success, the Metroliners reversed a long decline in ridership on the New York–Washington run.

On the Boston–New York run PC operated a United Aircraft TurboTrain in an effort to beat the 3-hour, 55-minute running time of the New Haven’s expresses of the early 1950s. Information about TurboTrain schedules was even more difficult for the public to obtain than Metroliner timetables.

The combination of untested equipment, track that had been allowed to deteriorate, and the general incongruity of space-age technology and traditional railroad thinking made the services the butt of considerable satire.

Amtrak took over PC’s intercity passenger service on May 1, 1971. The Metroliners were soon stored, and their schedules taken by Amfleet trains with accelerated timings. The TurboTrains were scrapped. The commuter service, already subsidized by local authorities, passed first to Conrail and then to other operating authorities.

Penn Central history aftermath

Penn Central history ended with bankruptcy. That was a cataclysmic event, both to the railroad industry and to the nation’s business community. The PC and its problems were the subject of more words than almost anything else in the railroad industry, everything from diatribes on the passenger business to analyses of the reason for PC’s collapse.

Few undertakings have had less auspicious beginnings than Conrail — and Conrail surprised everyone with its success.

The 1999 Conrail split between NS and CSX essentially accomplished what should have happened decades ago, thus sparing us the debacle which was Penn-Central.

WOuld the outcome have been different if the PRR and NYC had instead merged with a healthy coal hauler? Say, PRR with N&W and the NYC as a part of the Chessie System?