W. C. Janssen, Krambles-Peterson Archive

By G. Mac Sebree

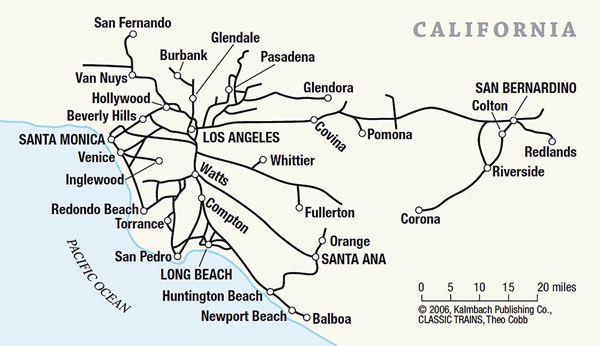

History of the Pacific Electric Railway

By any standard, the Pacific Electric was the largest interurban electric railway in the United States. It boasted more than 1,000 miles of track and had 1,000-plus cars. It played a major role in building up the vast open areas surrounding Los Angeles. The cities and towns that Pacific Electric created, however, became populated with an ever-increasing tide of automobiles, sowing the seeds of PE’s demise as a passenger carrier.

By any standard, the Pacific Electric was the largest interurban electric railway in the United States. It boasted more than 1,000 miles of track and had 1,000-plus cars. It played a major role in building up the vast open areas surrounding Los Angeles. The cities and towns that Pacific Electric created, however, became populated with an ever-increasing tide of automobiles, sowing the seeds of PE’s demise as a passenger carrier.

The story begins in 1895, when a line was completed from Los Angeles to Pasadena; a mere 10 years later, the system was virtually complete. To a great degree, PE was the brainchild of Henry Huntington, nephew of one of the Central Pacific’s “Big Four,” Collis P. Huntington. An active real-estate promoter, Henry needed the Big Red Cars and the transportation they provided to help sell lots and homes in the hinterlands.

His uncle’s Southern Pacific took control of the PE in 1911 in a deal that left the Los Angeles Railway, the narrow-gauge intracity system, in the nephew’s hands. The PE was built to standard gauge, and SP saw a brilliant future in freight for the interurban.

Big player, but not a Class I

Interurbans were not considered Class I railroads (or any other class — they were not “steam railroads”), but from the very start, PE was big business. The California Railroad Commission said the property was worth $100 million in Depression dollars. Atypically for an interurban, the system served as a gathering network for carload freight shipments from citrus groves, manufacturing plants, oil refineries, warehouses, and the harbor at San Pedro. The three line-haul railroads serving southern California — Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and especially SP — depended on the Pacific Electric to some degree.

Yet in its heyday, PE carried huge numbers of passengers. As late as 1953, 50 percent of its revenue came from riders — but absolutely none of its profit. An all-time list shows that PE operated 143 distinct passenger routes. Despite the so-called “Great Merger of 1911,” in which local and interurban services were supposedly separated, the heaviest PE passenger lines largely served the L.A. urban area. An example was the street-running L.A.–Hollywood–Beverly Hills line, in which two-car trains rumbled down Hollywood Boulevard at 10-minute intervals.

At one time or another, PE single-truck Birney cars plied local lines in Pasadena, Long Beach, Santa Monica, Redlands, Santa Ana, and San Pedro, although the 1920s were not far along before management sought to sell off or abandon these albatrosses.

George Krambles, Krambles-Peterson Archive

Boyhood interurban adventures

As a youngster living in the south coastal town of Laguna Beach during World War II, I was drawn to the PE. Monthly I would take a Greyhound bus to Long Beach, where I could get the Big Red Cars to downtown L.A. The usual drill was to get an early start, spend all day in the city, and as the shadows lengthened, board a speedy Santa Ana train, at whose terminal I could get a connecting local bus home.

Much as I thrilled to the big interurbans, it was to the Subway Terminal on Hill Street that I proceeded. Passing through an arcade, I would drop a dime into a farebox and head down a U-shaped ramp to the five-track subterranean terminal. Halfway down I would experience the acrid, ozone smells of traction, the rumble of cars entering and leaving, and growing anticipation.

As I faced the tunnel mouth, the first two tracks to the right were for Glendale–Burbank trains, formed mostly of PCC cars. The third and fourth tracks held cars to Beverly Hills via Hollywood Boulevard and the West Hollywood cars via Santa Monica Boulevard. The final track was reserved for trains to the “Valley” — North Hollywood and Van Nuys via Hollywood.

On the platforms I beheld a sea of PE’s famed “Hollywood Cars”: 52-foot, center-entrance, two-man vehicles of revered design. PE had 160 of these, and although the first of them dated to 1922, they had been modernized and, in fact, served until the mid-1950s alongside the PCCs.

The game was to beat the other passengers into the car so I could sit to the left of, and right beside, the motorman. Armed with a sack of donuts from one of the shops in the arcade, I would chomp my way through the day and across the miles. Any time left over would be spent on the yellow PCC and Birney streetcars of the Los Angeles Railway, Huntington’s old company.

Glamorous high-speed interurbans

More glamorous than the local lines were the high-speed interurbans to Long Beach, San Bernardino, Riverside, Santa Ana, Redondo Beach, Venice, and Newport Beach, most of which I rode — San Bernardino–Riverside and Redondo were already gone.

Hundreds of trains left downtown L.A. every day for every point of the compass. The Long Beach run from PE’s elevated 6th and Main Street station in downtown L.A. was said to be among the busiest, in 1925 boarding 25,000 people a day. (To show you how the world has grown, today’s light-rail Blue Line, laid precisely on the old PE for most of its length, amazingly has weekday boardings of up to 80,000!)

Overcoming growing misgivings at parent SP’s headquarters in San Francisco, PE in 1924 budgeted $1 million to build a 1,100-room office building and station near 5th and Hill in downtown L.A. and the aforementioned mile-long, double-track subway to the northwest, heading toward Hollywood, the San Fernando Valley, and Glendale-Burbank. Service started on February 7, 1926. It would be the last major expansion of the Pacific Electric.

The railway’s physical plant was impressive. Almost every line was double-track, at least along the inner portion. Two major routes enjoyed four-track sections, the inner tracks being for express trains. Most of the system was electrified at 600 volts D.C., but the long line to San Bernardino (the last built, opening in 1914) was pressurized at 1,200 volts, permitting fast running through some wide-open spaces.

Wide range of car types

Only superlatives can describe Pacific Electric’s wide range of passenger-car types, from a large fleet of wooden California-type cars (with both open and closed sections) in varied lengths and mechanical specifications, many inherited from predecessor companies, to longer and heavier steel cars ordered after the tragic Vineyard wreck of 1913, in which splintered wooden cars killed 16 people. The 1920s saw the arrival of whole fleets of both city and interurban cars, all steel, and all, of course, painted in PE’s signature medium red.

Inevitably, the Great Depression of the 1930s decimated PE’s ridership, and with prodding from SP headquarters, the interurban began to substitute buses, at first on the minor lines. Then, later in the decade, some major pruning began. There was only one hiccup. In 1936, PE shocked the public by substituting buses for electric cars on the second-busiest line out of the Subway Terminal, that to Glendale-Burbank. A few wooden cars continued to operate in the rush hours.

It didn’t work. The buses were smaller and slower, and the riders revolted. In 1939, the California State Railroad Commission ordered PE to not only restore rail service full-time, but to buy 30 PCC cars to replace the wooden rattletraps. The new cars, the first double-end, multiple-unit PCCs built, entered service in 1940.

During the war, PE suddenly needed more cars, and found them in the idled ranks of the discontinued San Francisco–Oakland East Bay “Red Electrics” and the Northwestern Pacific up in Marin County. PE used these cars, so big they were nicknamed “Blimps,” mostly on the heavy lines to Long Beach, San Pedro, and Santa Ana.

The Blimps were slow, but they worked out so well that PE modernized many for continued service after the war. All previous interurban records for crowd-swallowing were eclipsed in these cars. With their distinctive round front windows, the 72-foot monsters seated 111 passengers, plus standees beyond counting.

Post-WWII decline

After the war, though, things went downhill rapidly. As soon as buses were available, Pacific Electric began wholesale rail passenger-service abandonments. The new freeways were regarded as the rapid transit of the future. PE President Oscar Smith saw one possibility for saving rail service — if the state would pay. Just before the war, a short section of freeway between Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley had been built, with the PE tracks relocated to the center of the new highway.

Why not replicate this all over the basin? The PE would cooperate, but public officials turned a deaf ear, and that was that. Freight service, meanwhile, prospered, but by the mid-1950s, PE began replacing its electric locomotives and box motors with diesels (a few steam locomotives also had been used during the war). Over the years, PE rostered about 100 electric locomotives and at least 75 box motors — big business, indeed.

In 1953, PE sold its passenger service (four rail lines out of the 6th and Main station, two out of Subway Terminal, and many bus lines) to Metropolitan Coach Lines. The Metropolitan Transit Authority, first formed in 1951, bought MCL on March 3, 1958, and the end for electric passenger service came in 1961. SP continued the freight work with diesels, and merged PE away on August 13, 1965. Today under the Union Pacific shield, a good bit of the old PE freight lines remain in service, unique survivors, busier than ever.

General Motors introduced diesel buses in Lexington, Ky., to conduct a study on the cost-effectiveness of buses vs. trolleys, which was used to convince cities across the country to do so.