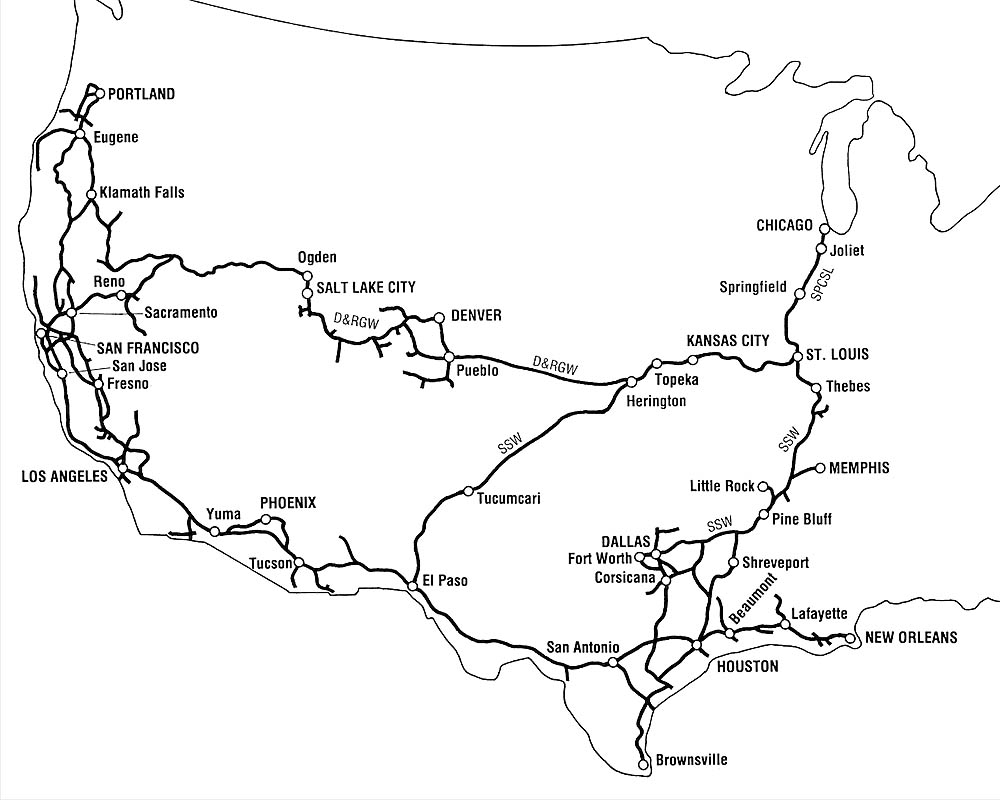

Southern Pacific history is made up of many little stories. Each for one of its many distinct mainline routes. Until the supermergers of recent decades, Southern Pacific was one of the largest railroads in the U. S., ranking third behind Pennsylvania and New York Central in operating revenue and second behind Santa Fe in route mileage. SP’s lines stretched over a greater distance than any other railroad—from New Orleans west to Los Angeles, then north to Portland, Ore., east from Sacramento to Ogden, Utah, and before 1951 down the west coast of Mexico to Guadalajara. It dominated transportation in California and was the only large railroad headquartered on the West Coast. Explaining Southern Pacific history route by route, much as its passenger timetables were arranged years ago, makes it easier to understand.

Overland Route history

California became a state in 1850. It would need a railroad to connect it to the rest of the country. The route that railroad should take posed a question: south toward the slave states or north toward the free states? The question was answered a decade later by the outbreak of the Civil War.

In 1852 the Sacramento Valley Rail Road engaged Theodore D. Judah to lay out its line from Sacramento east a few miles to Folsom and Placerville. The line was opened in 1856, but Judah had higher goals—a railroad over the Sierra Nevada to Virginia City, Nev. He scouted the mountains for a route and sought financial backing in San Francisco. That city considered itself a seaport, not the terminal of a railroad, but in Sacramento he obtained the backing of four merchants: Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker, and Leland Stanford—collectively, the Big Four. They incorporated the Central Pacific Railroad in June 1861.

In 1862 Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act. It provided for the incorporation of the Union Pacific Railroad to build westward (its eastern terminal, Omaha, was decided later), empowered the Central Pacific to build east, and provided loans and land for both efforts.

Construction of the CP began at Sacramento in January 1863. Its first train operated 18 miles east to what is now Roseville in November of that year. By 1867 CP had crossed the state line into Nevada, and on May 10, 1869, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific met at Promontory, Utah, creating the first transcontinental railroad.

California Lines history

After meeting the UP at Promontory, the Central Pacific was extended west from Sacramento to San Francisco Bay, first by construction of the Western Pacific Railroad to Oakland over Altamont Pass (don’t confuse this Western Pacific with the twentieth century railroad of the same name over the same pass, now part of Union Pacific), then by acquisition in 1876 of the California Pacific Railroad (“Cal-P”) from Sacramento to Vallejo.

In 1879 Central Pacific completed a line from Port Costa, across the Carquinez Strait from Vallejo, along the shore of San Francisco Bay to Oakland. Train ferries made the connection between Port Costa and Benicia (just east of Vallejo) until the construction of the bridge across Carquinez Strait in 1929.

The San Francisco & San Jose Railroad opened between the cities of its title in 1864, and in 1865, its owners incorporated the Southern Pacific Railroad to build south and east to New Orleans. History is unclear as to the next few years—who acquired whom, what was incorporated when—but by 1870 the Southern Pacific (possibly a new Southern Pacific) and the San Francisco & San Jose were in the hands of the Big Four. Construction started southeast from San Jose, and by 1871, the line had reached Tres Pinos, in the mountains east of Salinas and west—a long way west—of Fresno.

There was almost no population to support a railroad beyond Tres Pinos, so Southern Pacific changed its plans and started construction southeast through the San Joaquin Valley from Lathrop, 9 miles south of Stockton. The rails reached Fresno in 1872 and Sumner, across the Kern River from Bakersfield, at the end of 1874. The line was built by the Central Pacific as far south as Goshen Junction, 53 miles south of Fresno, where it intersected the original Southern Pacific survey. Beyond Goshen Junction, it was built by Southern Pacific.

The Tehachapi Mountains form the south end of the San Joaquin valley. To keep the grade over the mountains within limits, William Hood laid out a tortuous line that twists back and forth and at one point crosses over itself. The line reached a summit at Tehachapi, then descended directly to the northwest corner of the Mojave Desert. SP had intended to build southeast across the Mojave Desert to the Colorado River but it was induced to detour through Los Angeles (then barely more than a mission settlement).

The Coast Line, which was (and is) primarily a passenger route between San Francisco and Los Angeles, opened in 1901.

SP’s line from Mojave to Los Angeles was a detour. SP returned to Mojave and built east across the Mojave Desert to the Colorado River at Needles, Calif., not with the intention of continuing eastward but to connect with the Atlantic & Pacific—meeting it at the state line and saying, “Welcome to Southern Pacific country.” The eventual result of the line across the Mojave Desert was the Southern Pacific of Mexico.

History of the Sunset, Golden State Routes

SP built east from Los Angeles, reaching the Colorado River at Yuma, Ariz., in 1877. Further construction, as the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway, put the line through Deming, N. M., and a Santa Fe connection in 1881. Later that same year, SP reached El Paso, Texas, and then, 90 miles farther east, Sierra Blanca, a connection with Texas & Pacific Railway. These connections created two more transcontinental U. S. railroad routes.

SP pushed on east, meeting the line from San Antonio at the banks of the Pecos River in 1883. The railroad there was later relocated, crossing the Pecos on the highest bridge on a U. S. common carrier (320 feet).

In the mid-1880s the Rock Island planned a line southwest from Kansas to El Paso, and in 1902, it met the El Paso & Rock Island Railway at Santa Rosa, N. M. The El Paso–Santa Rosa line was the Eastern Division of the El Paso & Southwestern System. EP&SW’s Western Division consisted of a line from El Paso to Tucson, Ariz., parallel to SP but for much of the distance, 30 to 70 miles south of it. SP purchased the EP&SW in 1924.

Texas and Louisiana Lines Southern Pacific history

The Southern Pacific history east of El Paso grew from the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos & Colorado Railroad and the New Orleans, Opelousas & Great Western Railroad, both chartered in 1850. The BBB&C was reorganized as the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway in 1870. It reached San Antonio in 1877, engaged in some machinations with and against Jay Gould’s Missouri Pacific system, and continued building west. The Opelousas, sold in 1869 to steamship magnate Charles Morgan and later resold and reorganized as Morgan’s Louisiana & Texas Railroad, built across the bayou country west of New Orleans to form a New Orleans–Houston route in conjunction with the Louisiana Western and the Texas & New Orleans.

In 1934 all these railroads were consolidated as the Texas & New Orleans Railroad. Even after the repeal in 1967 of the article in the Texas constitution requiring railroads operating in Texas to be headquartered there, the T&NO lines were operated as a separate entity.

Shasta and Cascade Routes history

In 1870 Central Pacific acquired the California & Oregon Railroad, which had built north from Marysville. It pushed north through Redding, Calif., up the Sacramento River canyon, and over the Siskiyou Range to connect with the Oregon & California Railroad at Ashland, Ore., in 1887. SP acquired the O&C at that time, extending its system north to Portland. In 1909 SP opened a line from Black Butte, Calif., at the foot of Mount Shasta, northeast across the state line to Klamath Falls, Ore.

In 1926 SP opened the Natron Cutoff between Klamath Falls and Eugene, Ore. It had been conceived as a line southeast from Eugene to meet a proposed Union Pacific line west from the Idaho-Oregon border. That linkup never happened, but SP saw that extending this line south through the Klamath Basin might head off the Great Northern, which was constructing a line south from the Columbia River to connect with a Western Pacific line being pushed north from Keddie, Calif. As it turned out, GN wound up on SP rails between Chemult, Ore., and Klamath Falls. The new route had much easier grades and curves than the original route through Ashland, and it became SP’s main route in Oregon.

About the same time, SP opened a line from Klamath Falls southeast to the Overland Route at Fernley, Nev. Some of the Modoc Line, as it is called, was new construction; for other portions of it, SP purchased and standard-gauged the 3-foot gauge Nevada-California-Oregon Railway.

Construction of Shasta Dam between 1938 and 1942 required relocation of much of SP’s line in the lower Sacramento River canyon. The Pit River bridge, which carries both railroad and highway traffic, was at the time of its construction the highest in the U. S. (433 feet). Subsequent filling of Shasta Lake brought the water level up to just below the girders.

Southern Pacific history, Central Pacific, and Mr. Harriman

The four men who controlled the Central Pacific also controlled the Southern Pacific, and the two roads were operated as a unified system. By 1884 it was clear that corporate simplification was necessary. The most logical proposal, consolidating the two companies, was rejected. A new Southern Pacific Company was formed to replace the Southern Pacific Railroad. The Central Pacific Railroad leased its properties to the SP and was reorganized as the Central Pacific Railway.

As the 19th century closed, control of SP rested with C. P. Huntington, last survivor of the Big Four. Huntington died in 1900, and his SP stock was purchased by the Union Pacific, which had recently come under the control of E. H. Harriman.

Harriman had acquired a UP that had fallen on hard times. It consisted essentially of lines from Omaha and Kansas City west through Cheyenne to Ogden. Harriman immediately undertook a complete rebuilding of the UP and reacquired the route northwest through Idaho to Portland, Ore., that UP had lost a few years before. Without ownership or control of the Central Pacific from Ogden to California, though, UP’s line to Ogden was worthless.

The Southern Pacific was in good condition, but Harriman soon undertook three major improvements on SP’s Overland Route: the Lucin Cutoff across the Great Salt Lake, shortening the Oakland–Ogden distance by 44 miles (and bypassing Promontory); a second track over the Sierra, in many places with an easier grade; and automatic block signaling. One of Harriman’s improvements in California was the Bayshore Cutoff south of San Francisco, which replaced a steep inland route with a water-level route along the shore of San Francisco Bay.

Meanwhile President Theodore Roosevelt had begun to consider the problems that big business posed for the free enterprise system. He focused his attention on Harriman, the Union Pacific, and the Southern Pacific.

The upshot was that UP had to sell its SP stock, and SP had to justify its retention of Central Pacific. Divestiture of Central Pacific would have ripped the heart out of Southern Pacific’s network of lines in California and Oregon. Central Pacific’s principal routes were from Oakland through Sacramento and Reno to Ogden; from Fernley, Nev., northwest to Susanville, Calif.; from Hazen, Nev., down to Mojave (mostly narrow gauge); from Roseville north to Hornbrook, Calif., on the Siskiyou Route and to Kirk, Ore., north of Klamath Falls; and from Stockton through Fresno to Goshen Junction. The Natron Cutoff and the Modoc line, both built in the late 1920s, were also Central Pacific routes. The process of justifying SP’s ownership of Central Pacific to government agencies continued for years, consuming management time and creating an atmosphere of uncertainty. Central Pacific’s corporate existence continued until 1959.

Southern Pacific mergers history

Southern Pacific and Santa Fe announced their merger proposal in May 1980, called it off later that year, and revived it in 1983. On Dec. 23, 1983, Santa Fe Industries and Southern Pacific Company, the parent companies of the two railroads, were absorbed by the new Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corporation. The two railroads remained separate but went so far as to paint and partly letter several locomotives for the Southern Pacific & Santa Fe Railway.

The Interstate Commerce Commission turned down the request for merger, rejected the subsequent appeal, and ordered SFSP Corp. to divest itself of one railroad. Offers to buy SP came from Kansas City Southern, Guilford Transportation Industries, SP management, and Rio Grande Industries, parent of the Denver & Rio Grande Western. On Aug. 9, 1988, the ICC approved sale of the SP to Rio Grande Industries. The sale was completed on Oct. 13, 1988.

The name of the new system was Southern Pacific Lines. The identity and image of the Denver & Rio Grande Western were replaced by those of SP—much like Cotton Belt came to look like its parent, SP.

In 1991 SP sold its San Francisco–San Jose line and the commuter business it operated for the California Department of Transportation to San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties (retaining freight rights). The Peninsula Corridor Joint Powers Board assumed responsibility for funding and operating the service. Amtrak took over actual operation of the Peninsula commuter trains on July 1, 1992.

Union Pacific purchased the Southern Pacific on Sept. 12, 1996. SP enthusiasts can take pleasure in knowing that technically SP merged UP, not the other way around. On Feb. 1, 1998, the Southern Pacific Transportation Company (a Delaware corporation) merged the Union Pacific Railroad and was then renamed the Union Pacific Railroad Company. Thus ended more than a century of Southern Pacific history.

Denver’s Phillip Anschutz (who earned his money in oil and gas) first bought the D&RGW on the cheap. Then ,when the SP came up for sale, he also bough that RR (again on the cheap) and made the merger of all of his rail lines into the new SP. He held this rail system long enough to get the UP to buy him out at a much higher price than he had paid for any of the lines he had bought out. Check out this smart oil man on the net. (He started with Anschutz Ranch East Crude Oil, if I am not mistaken — where I first ran into him).