One of the fascinating aspects of being actively involved in firing and running steam locomotives was discovering that each one had its own personality. In the case of a class of engines, sometimes the entire group would demonstrate similar characteristics, but seemingly there would always be one or more in the class that were superior to their stablemates. Occasionally, though, a manufacturer would produce a class of “lemons,” for which any reasonable explanation for the deficiency is elusive.

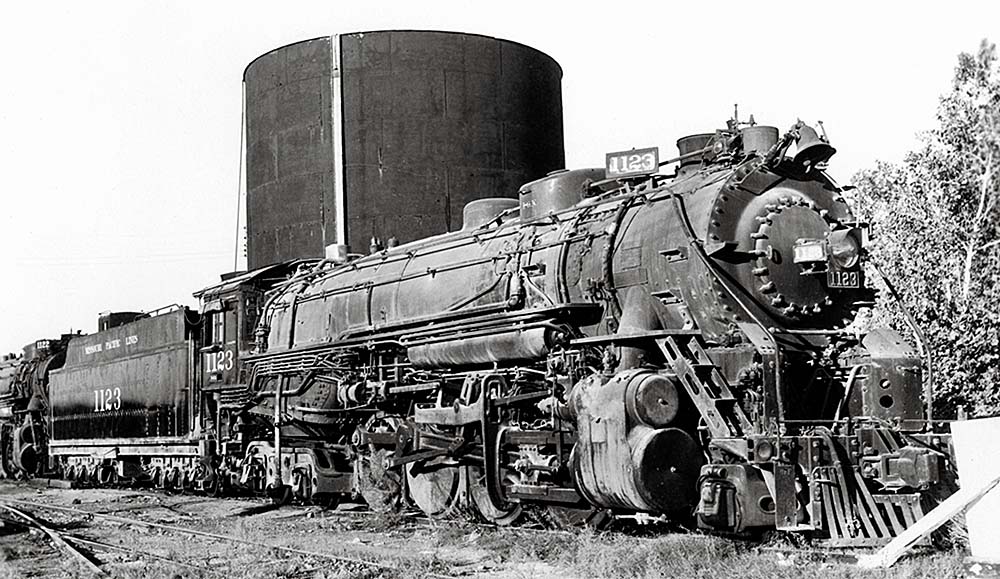

This was the case, in my opinion, with Missouri Pacific’s obscure group of five 1121-series 2-8-4 Berkshires, built by American Locomotive Co. in November 1928 for MP’s International-Great Northern subsidiary. I observed these engines for several years running into Houston before I was hired out there with the I-GN as a student fireman in March 1942. At that time, I was looking forward to working on the 2-8-4s because I considered them to be state-of-the-art Super Power. The reality turned out to be somewhat disappointing.

The I-GN, known to many as “the Jenny,” totaled 1,159 miles, all in the Lone Star State, with main lines extending from Longview (on the main line of Texas & Pacific, also an MP property) southwest through Palestine (PAL-uh-steen) and San Antonio to Laredo; from Palestine south to Houston; and from Houston north to Fort Worth. Dating from an 1873 merger that created the International & Great Northern, the road emerged from a second receivership in 1914 as the I-GN (with a hyphen); it became part of the MoPac family in 1924.

By 1928, the I-GN was working with a reliable group of 4-6-0s and classes of 22 Consolidations, 10 light Mikados from the early 1920s, and 10 somewhat larger Mikes from 1926. The latter were part of a push for new power by parent MP, which for I-GN included five big 4-6-2s and five modern 0-8-0s.

The five 2-8-4s were part of this push, being patterned after Lima’s A-1 prototype, which MoPac had tested in 1926. The 1121-1125 series shared basic specs with 55 Boston & Albany, 25 Boston & Maine, and 50 Illinois Central 2-8-4s, all built by Lima during 1926-1930, and 12 Alco 2-8-4s for Chicago & North Western in August and September 1927.

Neil Carlson’s authoritative article, “The Berkshire Story,” in Steam Glory 2 of 2006, documented a generally efficient and successful wheel arrangement. The article’s accompanying chart, which compared the variations in 2-8-4 design, was interesting. It seems that these all were an effort to produce a “universal freight locomotive,” and most of the engines constructed from these plans, regardless of their builder, met the expectations of their owners as well as doing everything that Super Power proponent Lima had envisioned. The I-GN’s perhaps were an exception.

Oddly enough, these five engines were built as coal burners, strange because I-GN locomotives for decades all had been oil-burners except for four light 2-8-2’s leased from MP for a lignite-burning experiment. According to the late steam authority Lloyd E. Stagner, in his “Lonesome Lone Star Berkshires” about these same engines in November 1988 Trains, the 1121 series debuted on MP’s Omaha Division, and I long surmised that they were built as coal burners so MoPac could test them before ordering its own Berks. The latter, 25 in the 1901 series, were Lima-built; both groups were class BK-63. (Interestingly, the 1901-series 2-8-4’s were rebuilt into 4-8-4s during 1940-42 at the Sedalia, Mo., shops, with their 63-inch drivers replaced by 75-inch ones.)

Needless to say, the 1121 series — which arrived on I-GN in May 1930 coincident with the arrival up north of the first of the Limas — worked on the I-GN as oil burners. Records indicate the coal-to-oil conversion was done that June.

My first trip as a student fireman was on 1117, a heavy Mike in the 1111-1120 series. She rode and steamed beautifully, and even though I was a rookie, the engineer gave me an “OK” on my student letter after I’d fired for about 40 miles. I next worked several shifts in the yard, then made an unofficial trip to Galveston on a passenger train before finally climbing onto a 2-8-4, the 1124, to make a night run to Palestine, 154 miles north. I was with an excellent crew who put me to work on the left side as soon as we started. I soon found, though, that the 1124 was not the engine 1117 was; the 2-8-4’s fire was harder to regulate, and she was a surprisingly rough rider. I made another trip on 1124, but it was no better than the first.

Students had to pay their own way in those days, and I was short on money, so I kept moving and got my final OK in 10 days. In the following few months I worked a variety of jobs off the Houston extra board, then got cut off in July, after which I had a brief period of employment on the Santa Fe in Winslow, Ariz. Eventually, after being called back to the I-GN, I worked steadily through winter and spring. In August 1943 I got married, after which we moved to Palestine, where I worked on a through freight turn until spring 1944, when my U.S. Army draft number came up.

My freight run was mainly on the Taylor Subdivision, part of the 340-mile Longview-San Antonio line on which through freights changed engine crews at Palestine, 81 miles out, and Taylor, 64 miles farther south. Most of our power was 2-8-2s in the 1111 series plus a few 1200s from “the Mop” proper.

Early in 1944, I was called for Second 7, a 16-car troop extra from Palestine to Taylor, with the 1125, which steamed as poorly as the 1124. In the same winter, with snow and ice on the ground, I caught hot train 66, carrying mostly perishables, north out of Taylor with the 1122. I had an extra board engineer, “Hop” Green, with whom I’d worked a number of times, and we’d always gotten along well. On the first hard climb out of Taylor, the 1122 steamed fairly well. From there north it was an 8-mile descent, upon which Hop eased off to just over a half throttle. That’s where the rough ride began.

The slack between the engine and tender was excessive—I had no idea an engine with a four-wheel Delta trailing truck could ride so rough. She would steady out to some extent when working hard, but on this roller-coaster section of line, the beating and pounding was unbelievable. Starting down Gause Hill, a sort of “race track,” Hop reduced the throttle opening again, at which time something happened to cause the color of the fire to turn a reddish hue instead of bright yellow … and the steam pressure began dropping.

We rolled into Valley Junction, crossing the Fort Worth-Houston line, and stopped at the water plug. After taking water, I returned to the cab to find Hop peering into the firebox. What a mess! All the brickwork had collapsed, blocking the path of the flame from the burner. We poked around with the carbon bar but could not move any of the tightly wedged bricks. No other engine was in the vicinity, so we decided to proceed and see if we could somehow finish the trip. It was a matter of swapping steam and water, rolling downgrade with the blower on hard while trying to get extra water in the boiler, then struggling upgrade. We made it to the terminal at Palestine with difficulty, hoping we’d never have another such trip. Before leaving for the service, though, in March 1944, I did have a better trip, with the 1121, running 50 to 55 mph with a 36-car stock extra from Taylor to Valley Junction.

Fast forward to 1946. I had returned to Palestine from my service in the Army’s 749th Railway Operating Battalion, in which I’d been promoted to engineer. I’d bid in a freight turn on I-GN’s Gulf Division, working to either Houston or Longview. One evening I was called for the night freight to Houston with an extra-board engineer known as “Smoky.” He was a grumpy, irritable sort, and to make things worse, our engine was the 1122. We had less than full tonnage, so perhaps the run might not be too bad. The 1122 bucked and slammed around as usual, but she was steaming pretty well until we were downgrade leaving Latexo, when the smoke from the stack became black, the fire turned red, and I thought of the trip I’d made on her earlier.

Smoky stopped at Crockett to take water, and upon checking the firebox I found the brickwork to be intact. When we pulled out, though, the smoking began again, and Smoky started raving, wondering what was the matter. I told him my guess was the brackets holding the petticoat pipe had been broken by the severe shaking of the engine, allowing the petticoat pipe to drop down around the exhaust nozzle, which would effectively kill the draft. Smoky continued his tirade about smart-aleck Army men who had run engines for a few months and then came home to tell experienced men a dumb story about petticoat pipes. I kept quiet, since I had my hands full trying to keep water up and a little steam.

We finally reached Houston, looking like fugitives from a coal mine. Smoky made out the work report with the notation “engine not steaming.” As luck would have it, that night we were called to go north with the same engine, on train 64. The roundhouse foreman came out, and Smoky asked him what problem he had discovered. The foreman answered that the brackets holding the petticoat had broken, letting the pipe cover the exhaust nozzle, which killed the draft. I’ll have to give Smoky credit; he did apologize to me for his unkind remarks earlier, and we had a fair return trip.

In April 1947, I’d gone north to Longview, and for my southbound return, I drew the 1124 on a 40-car oil train to Palestine. The Berk rode surprisingly well and steamed fine, hitting 55 mph through the bottoms at Reeves, but then she “laid down” on the 1.17% grade and we had to double the train to Overton. As often happened, the booster was out of order. If the booster was operable, it could be a great help, but the MoPac theory seemed to be that a booster was intended to pull tonnage rather than to give an extra boost when in danger of stalling on a grade. This resulted in the boosters being inoperative or in the shop for repairs much of the time.

Not every I-GN Berkshire trip gave me problems. That same spring, I had the 1123 on first 66 from Palestine north to Longview, and the Berk rode better than usual and steamed well. I was amazed, since I’d come into Palestine from Houston 8 hours earlier with her, and she’d steamed poorly all the way, even though my fireman was experienced. Moreover, no work had been done on her during the layover at Palestine.

I studied the specifications of the various Berkshires in Carlson’s 2006 story, and learned that the 1121-1125 group was practically identical to the rest of the A-1s. Our five I-GN 2-8-4s were not without their good points. Their big tenders allowed fewer water stops, and twin air pumps allowed long trains to be pumped up quickly. Further, many enginemen admired their good looks. However, the engines were weak at low speeds — they simply would not lug below about 15 mph. It was mandatory that the boiler pressure be maintained as near 240 PSI as possible, with the water carried at not over half the glass. I’ve always felt those Berkshires might have been better engines with full cut-off.

My experience with the I-GN 2-8-4s stands in contrast to another group of Super Power engines I knew well, Texas & Pacific’s 2-10-4s. I worked many trips on T&P’s Texas types and found them to be superb-riding engines. They would pull hard at low speeds and were good steamers. Our five Berks were no faster than our big Mikes, while the big T&P engines, after new rods were installed, were listed as 60-mph engines.

During the latter years of World War II, the Sunshine Specials, the MoPac system’s premier passenger trains in Texas, were running quite heavy, often with 20 to 22 heavyweight cars. The T&P assigned two of its Texas types to passenger service to handle these long trains from Longview east to Texarkana, 90 miles. At the same time on these trains, the I-GN was doubleheading heavy Pacifics between Palestine and Longview. Then the powers-that-be tried to assign one 2-8-4 to the train; I suppose they thought this could be accomplished, saving the wages of an engine crew. The I-GN Berkshire experiment proved to be a fast failure, though, for after only a month or so, the doubleheading of 4-6-2s resumed and continued into 1946. I was still serving in the Army at that time, but upon returning home I found two Pacifics still on that job.

In 1947, what would total 16 MoPac F3 diesel freight units began to arrive from Electro-Motive Division, and then 16 F7s in 1949, but for two or three years there was still plenty of work on the I-GN lines for heavy steam freight engines. All 20 of our own Mikados were kept busy, and we still had two MoPac Mikes in the 1401 series leased, plus one of the 1201 series. Some 2-8-2s remained in service right up to the end of steam on the I-GN, which occurred in June 1954, according to Lloyd Stagner. I’d been an engineer in the Army, but after my return and promotion to the right-hand side, my very first trip as engineer on the I-GN was on the 1248, which later, ironically, pulled our last steam-powered freight, a day after I had fired her.

To me, it was significant that the 2-8-2s remained in service for so long, while the five Berkshires were the first large freight engines I-GN took out of service and placed in serviceable storage, in 1948 as I recall. Three were stored in Palestine and two in San Antonio. The 1125, and possibly others in the class, were sent north to help out on MoPac’s North Little Rock, Ark.-Dupo, Ill., main line during a coal strike in early 1950, but they saw little if any use when they returned to the I-GN. They were retired in spring 1952 and later scrapped. I suppose the reason for the 1121 series’ relatively poor performance will forever be a mystery that motive-power enthusiasts may ponder.

Who is the author of this piece? I find no reference to him.

Looks like Brian Schmidt owns the by-line so I assume he was the author and the protagonist in this article…