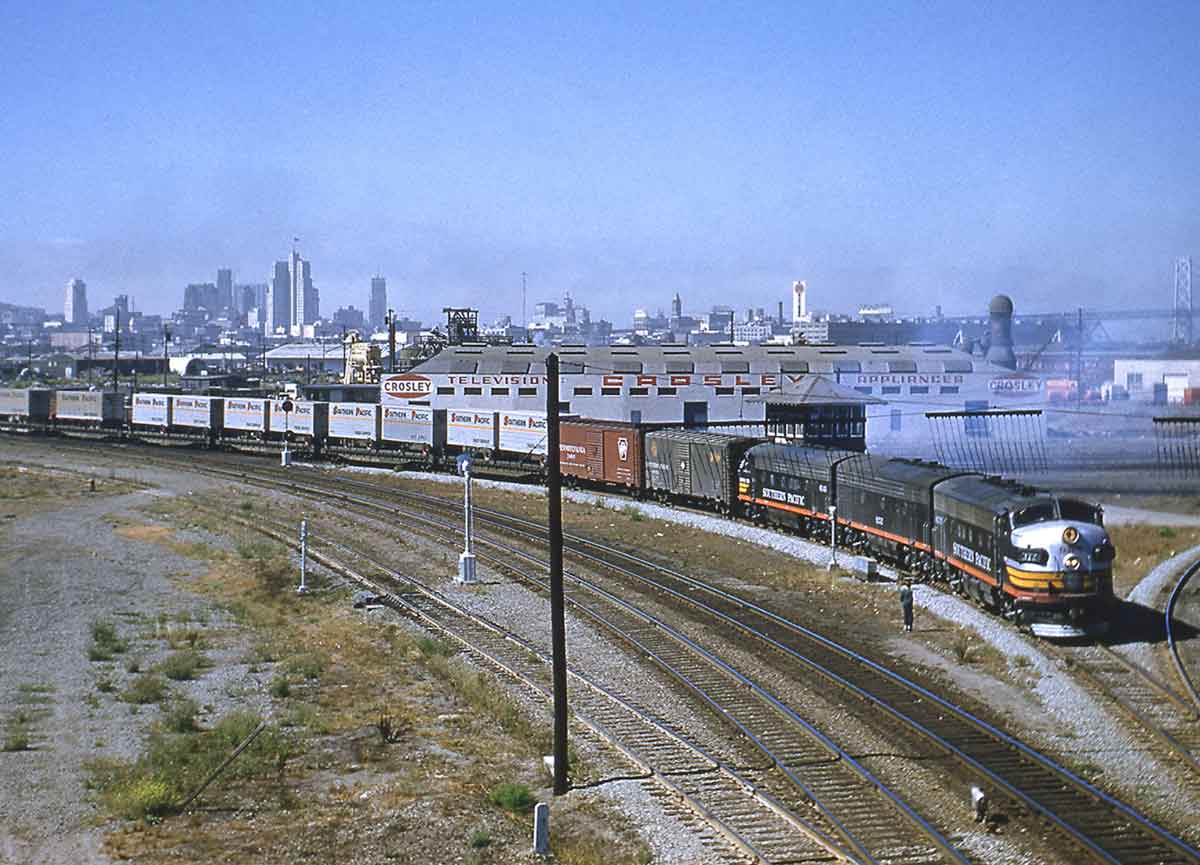

The Southern Pacific locomotive roster was expansive. A headlight breaking the horizon in the 1960s meant one thing; you never were sure what the motive power would be. In its latter years, despite having hundreds of Electro-Motive Division Geeps and SDs and General Electric U-Boats of all models, SP would assemble whatever was available on the ready tracks to power the next train out. But what was an operating department’s nightmare was almost always a railfan’s delight.

At its most complex, Southern Pacific rostered locomotives from a half-dozen builders, including EMD, Alco, GE, Fairbanks-Morse, Baldwin, and Krauss-Maffei.

At this point, the question that bubbles up to the surface is: why would a company do that to itself? The complicated parts supplies, filters, gaskets, tooling, and idiosyncrasies of such a collection is not only inefficient but time consuming. Not to mention the training of everyone who worked on them.

All true. But during the early days of railroad dieselization, railroads were pounding down the doors for diesels and not every company could or would wait their turn. Besides, different builders offered unique choices. If a company wanted road-switchers it would have to look at Alco, Baldwin, or FM as EMD was yet to offer such a model. Financing was another consideration. Reputation another.

To prove my point, look at the Southern Pacific locomotive roster mishmash through the eyes of the lineside hobbyist watching that headlight that broke the horizon now close enough to be a recognizable train.

Road units were predominantly EMD, GE, and Alco hood units in that numerical order. With SP any model could eventually be found everywhere but mostly, GEs worked California east to Houston and up the Coast Line, with Alcos corralled in Texas until they were rebuilt as heavy switchers and assigned to major yards throughout the system. EMD products could be found everywhere. Oddballs, such as the three EMD DD35s and three GE U50s, were usually at home on the Sunset Route.

The Krauss-Maffei units, a small fleet of 4,000 hp, six-axle German-built road locomotives in both cab and hood design wound up in California’s San Joaquin Valley service after failing in their original Donner Pass assignment. Oh, yes, you can add three Alco DH643s, an American builder’s version of the KMs, to the mix.

The remnants of SP’s passenger diesel fleet – the Alco PAs and PBs were gone – included EMD E7s, a lone E8, and E9s, a small squad of EMD FP7s, and a handful of F units equipped with boiler controls. San Francisco Bay area commuter locomotives were a combination of EMD SDs, Geeps, a single FP7 inherited from the Cotton Belt, and, of course, a roster of crowd-pleasing FM H24-66 “Train Masters” exiled from their original freight assignments out of El Paso, Texas.

The switcher roster was even more complicated.

For many years Baldwin and Alco end-cab switchers were the backbone of the fleet, with a lesser quantity of EMDs. As the other builders left the business and their products were wearing out, more and more end-cab EMD models replaced them, culminating in a massive order of 1,500 hp SW1500s in the 1960s and a smaller quantity of both MP15DC and MP15AC models in the 1970s.

As if the roster needed to be more convoluted, 21 GE 70-tonners, and a handful of 44 tonners filled in on lightly railed branch lines and industrial backwaters. Heavy switching, hump assignments, branches, and even secondary mainline duties were entrusted to a fleet of Baldwin road-switchers — both 1,500 and 1,600 hp designs — encompassing C-C and A1A-A1A configuration.

To be fair, there were many assignments where SP tried to keep specific units working specific jobs — 10 GE U28Cs were purchased for Kaiser Steel ore trains from the company’s Eagle Mountain Mine in the California desert to its plant in Fontana to the west and the L.A.-Bakersfield route over the Tehachapi Mountains was usually the domain of EMD SD9s and SD35s, plus 21 Alco RSD12s – but seemingly forever power short ready tracks assembled whatever was available with little regard for builder, model, or horsepower.

The biggest alphabet soup of locomotive consists could usually be found on secondary and local trains throughout the system.

Examples abound: Transfer jobs from Los Angeles to the Harbor to the south and to the newer major yard in Colton, about 80 miles east would require four or more units to move them over the road, resulting in power that was soon in need of servicing being kept close to home. More than once a trio of four- and six-axle road-switchers would be trailing an FP7A unit. Combinations of Alco RSD12s and EMD SD7s, all yard power by this time, would be called on to work the cuts as well. And long after they were banished from the high iron, a pair of back-to-back Baldwin S12 switchers would work a local to an outlying local yard. Similar situations could be found almost everywhere else on the system.

By 1996, when the Southern Pacific locomotive roster was absorbed into the Union Pacific, the Southern Pacific locomotive roster was far less complicated, but even then, for every unit that had a counterpart on UP, there were many that the latter just had to sideline instead of making their roster more complex.

Thank you, John!

Great article David, brings back memories of 1957-1963 watching and hearing the westbound trains coming off Beaumont Pass with dynamics on–what a show—Thanks for the memories!!