Prior to the Hudsons, Mountains, and Northerns, the 4-6-2 Pacific-type was celebrated as THE passenger locomotive at the turn of the 20th century. Outperformed in later years by their bigger, faster, and stronger successors, the smaller racehorses continued to hold their own until the end of steam along North America’s railroads. Though, it can be said that operating opportunities in the preservation era have been few and far between.

Like past designs, the origin of the Pacific came from the tried-and-true method: Make it bigger. The template was from the previous 4-4-2 and 4-6-0 wheel arrangements with a focus on passenger service. The earliest 4-6-2s were built by the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1901 for 3-foot, 6-inch-gauge rail lines in New Zealand. However, according to former Trains’ Editor David P. Morgan in the September 1988 issue, the world’s first was reported to have been built in 1886 in the form of a twin-firebox Camelback named Duplex — in service until 1898, but before being converted into a 4-6-0.

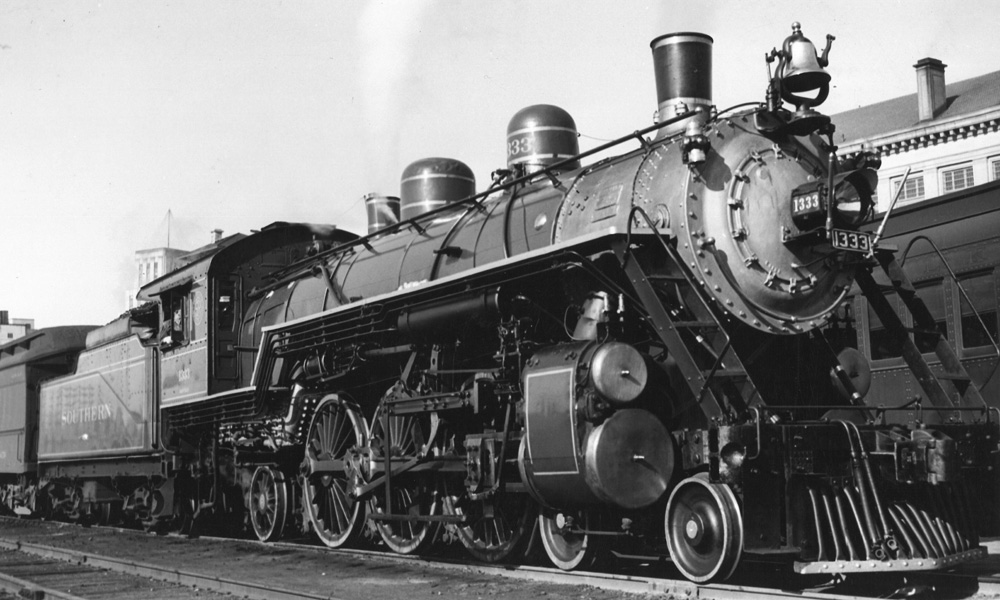

It wasn’t until 1902 when the first 4-6-2s for U.S. railroads were delivered to the Missouri Pacific. From the nicknamed MoPac came the nickname that would be synonymous with the upstart wheel arrangement, “Pacific.” The timing for the introduction couldn’t have been better with the increase in passenger demand and heavier coaches in the early 1900s. The deeper firebox, longer boiler, and high-profiled drivers of the 4-6-2 resulted in high-speed capabilities many railroads strived for. Advancements in steam technology at the time — such as superheaters and Walschaerts and Baker-style valve gear — boosted the Pacifics’ value.

How valued were these locomotives? It’s estimated in Alfred W. Bruce’s The Steam Locomotive in America that 6,800 Pacifics were produced in the U.S. with 800 being exports. During World War I, the United States Railroad Administration rolled out their own fleet of standardized, light- and heavy-type 4-6-2s to handle the wartime traffic while being adaptive to any rail line throughout the country. If a railroad was offering passenger service, whether be a local or limited, chances are they rostered a Pacific. On an international scale, two of arguably the most famous steam locomotives in the world are part of the 4-6-2 family: A3-class No. 4472 Flying Scotsman and A4-class No. 4468 Mallard, both from the United Kingdom’s London and North Eastern Railway.

At the peak of North American passenger rail by the 1920s, the Pacifics, too, became a victim of continual progress. Longer, heavier, premier trains with many traversing rugged terrains were becoming too much for a single locomotive to handle. The tried-and-true method of “make it bigger” returned with the introduction of the 4-6-4s, 4-8-2s, and 4-8-4s.

The Reading Co. became the last U.S. railroad to receive a fleet of Pacifics in 1948. While the demoted speedsters continued to hold up on less-glamourous passenger and commuter trains, the secondhand market for other work such as freight didn’t bode well. The 4-6-2’s greatest strength, primarily as a racehorse, became the ultimate weakness due to limitations as a workhorse.

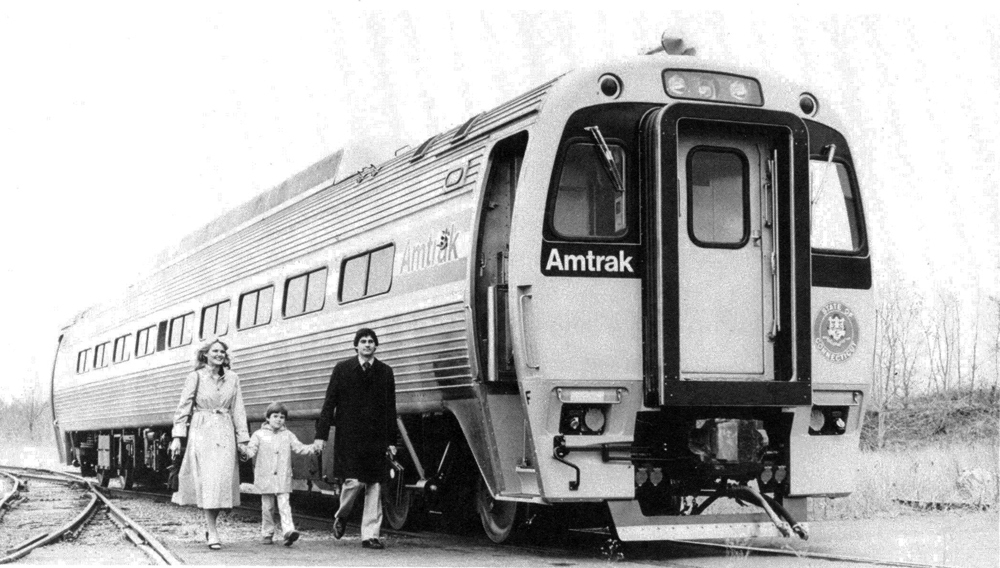

When ultimately retired in favor of diesel-electric locomotives by the railroads, a healthy amount of Pacifics were saved from scrappage. The number of survivors may be considered miniscule compared to other locomotive types that saw sanctuary during the preservation movement. Despite not always being ideal for tourist railroads and mainline excursions — too big and fast for the former and too small and underpowered for the latter — the 4-6-4 Pacific-type has found operational opportunities in the modern era with a few locomotives still in service today.

Check your last paragraph, and correct the wheel arrangement. “4-6-4”