The New York Central 4-8-2 Mohawks were the ultimate dual-service steam locomotives.

For some railroads in the steam era, it wasn’t enough to have success with a single example of a standard wheel arrangement. Instead, new competitive challenges and evolving technology often caused railroads to rethink a given locomotive class and turn it almost entirely upside down.

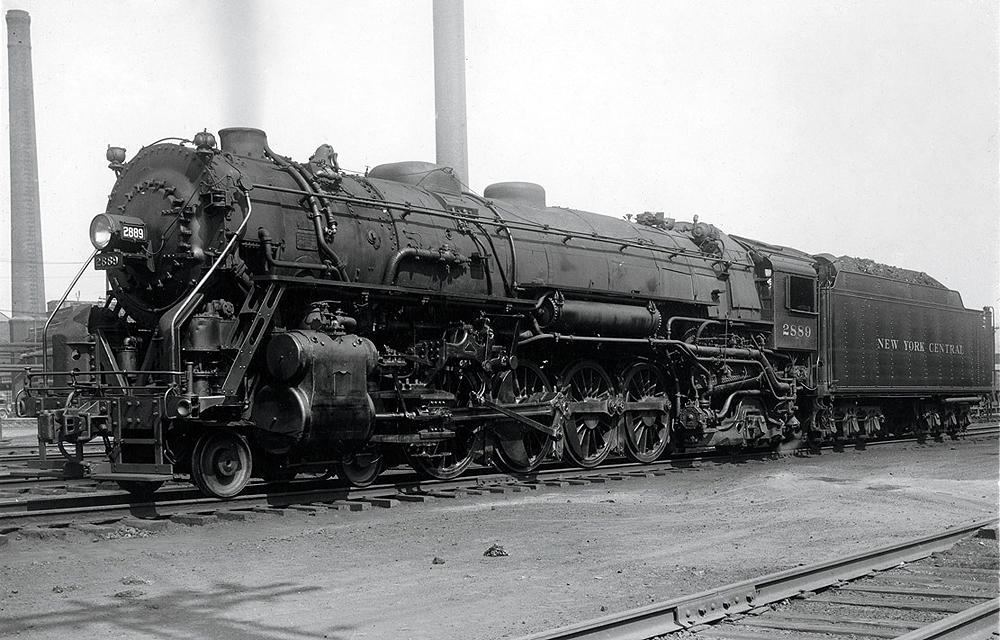

One of the best examples is New York Central, which went whole hog on the 4-8-2 between 1916 and 1930, buying 485 copies of a rather conventional freight engine in the L-1 and L-2 class, only to turn around a decade later and come up with a new, much more impressive 4-8-2 in the 115 examples of the L-3 and L-4 classes. The latter engines truly were dual-service machines, handsomely designed and capable of handling heavy freight as well as fast passenger trains. For all of them, Central chose the name “Mohawk”; the 4-8-2’s usual “Mountain” moniker just wouldn’t do on the Water Level Route. In the end, NYC employed 600 Mohawks in various classes, by far the most of any U.S. railroad. The closest competitor was the Pennsylvania, with 224 engines in the M1a and M1b classes.

The 4-8-2 wheel arrangement was already popular around the world when Chesapeake & Ohio became the first to employ the type in the U.S. in 1911. The NYC, eager to improve upon the performance of its huge fleet of H-class 2-8-2s, quickly followed suit with an order to American Locomotive and Lima for 185 L-1 engines delivered from 1916 through 1918. The Central was impressed enough with the Mohawk’s performance that it ordered 300 more from Alco, delivered from 1925 to 1930 in various iterations of the L-2 class. The latter engines were a significant improvement over the earlier Mohawks, with larger boilers, larger tenders, and generally equipped with Elesco feedwater heaters installed either in front of the smokestack in a “beetle-browed” fashion, or countersunk into the contour of the smokebox.

It’s a measure of the long tenure of the Mohawk that the first engines were designed to be hand-fired, as they were delivered before the large-scale use of mechanical stokers. Given the size and fuel appetite of the L-1, this situation soon proved untenable and by the early 1920s older engines were refitted with duplex stokers, a practice made permanent in future orders.

The Mohawk reached its fullest potential with the 115 engines in the L-3 and L4 classes, which arrived in two orders of 50 each in 1940-42 and 1942-44. Designed as true dual-service engines, they boasted 72-inch drivers to sustain 80-mph speeds on passenger trains. Other refinements included roller bearings on most axles (and on driving axles on those designed for passenger service), lightweight rods and reciprocating parts, disc drivers, and much larger tenders. There were 25 passenger engines in the L-3 order specifically outfitted with cast-steel pilots with drop couplers, giving the engines a close resemblance to New York Central’s famous 4-6-4 J-class Hudsons; freight-only models kept the older footboard-style pilot.

The subsequent order of L-4 engines saw minor refinements. Interestingly, in order to reduce weight on the trailing axle, late-model L-class engines were designed with a substantial use of aluminum in the cabs, as well as placement of the stoker engines within the tender instead of under the cab. All of these improvements helped the later Mohawks reliably deliver about 60,000 pounds of tractive force, as well as deliver those much-desired passenger-train speeds.

The Mohawk’s value to New York Central was unmistakable, as outlined by author Thomas H. Gerbracht in his two-volume history of the entire class of NYC 4-8-2s, published by the New York Central System Historical Society. “There was a time in the railroad’s history when a roundhouse foreman was delighted if he had a few modern Mohawks that he could assign to any type of train,” writes Gerbracht. “There was more than one chief dispatcher who would be amazed at the ability of a late Mohawk to get over the road with any tonnage assigned. And there was probably more than one finance guy at HQ who would truly recognize the economic impact that the late Mohawks delivered to the railroad’s bottom line.”

Despite their high performance, the New York Central 4-8-2 Mohawks suffered the same fate as nearly all of NYC steam: completely dieselization by mid-1957. Fortunately, two of the 4-8-2s escaped the torch. The National Museum of Transportation in St. Louis displays one of the older Mohawks, L-2d No. 2933, built in 1929, while the National New York Central Museum in Elkhart, Ind., preserves L-3a No. 3001, delivered in 1940.

Dear Mr. O’Keefe,

Thank you for bringing among the most significant steam locomotives in american practice to your readers attention.

However, please advise your readers on bibliographic sources – – – for some of the things that you bring up need better clarification.

1) The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive (VOL I) F.M. Swengel (Midwest Rail Publications 1967) – – – pp147 feature a 69″ drivered Pacific K11 (1910) was a freight locomotive.

Books by Arnold Haas (Memories of NYC Steam) and NYC Steam Power by Alvin Staufer seem to indicate that only L3A was fitted with 72-inch drivers as an experiment before ordering L4s from Lima

Regards – Charles Gasper

Santa Ana, CA

A fine article with a few corrections needed. Only the 50 L-4s were built with 72″ drivers, although the first L-3a, no. 3000, later had its original 69″ drivers replaced with 72″. This proved the merit of the larger driving wheels, which were then applied to the L-4s. All 550 L-1s, L-2s, and L-3s were built with 69″ drivers. And the PRR had 300 Mountains, 200 M1s and 100 M1as, not 224.