Budd Slumbercoaches were born of a desire to serve budget-conscious leisure travelers in the mid-20th century.

As economic conditions improved during the 1920s and more people could afford to travel, there was demand for a less costly but more comfortable means of travel, particularly for the long-haul routes between Midwest and West Coast points, which generally required two nights enroute. Thus, a “tourist” class product emerged, via the use of older sleeping cars, with fewer of the expected Pullman amenities. This type of service persisted in Canada into the 1960s, after heavyweight Pullmans in 1955 were added to the consists of Canadian Pacific’s new streamlined Canadian.

During the pre-World War II years, there were experiments with various kinds of “coach-sleeper” accommodations, but none really caught on. The reclining-seat coach had helped to some extent, and this was improved further in postwar equipment by the “leg-rest” seat, which, while not a bed, did allow a somewhat more comfortable overnight travel experience.

By the late 1950s intercity rail passenger service had entered a severe decline. This, of course, also impacted the builders of railroad cars, which were now essentially in the doldrums. To address this situation, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy in 1956 ordered a new type of car from Budd, designated as a “Slumbercoach” for use on the Denver Zephyr.

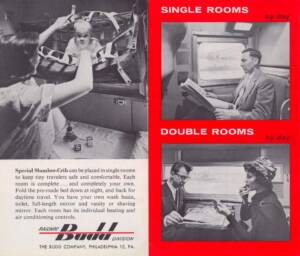

A typical postwar lightweight sleeping car included 20-24 beds; the new Budd Slumbercoaches had 40, with 8 double rooms and 24 singles, the latter arranged in a staggered “duplex” arrangement. They were less luxurious than regular sleepers, but their economy-version beds still were better than even a leg-rest coach seat as far as passengers were concerned.

A contemporaneous foldout brochure issued by Budd boldly called out the essential value proposition for this equipment on its cover: “Travel in privacy in a room of your own at low coach fares,” plus, of course, a modest accommodation charge. In a nod to travelers with small children there was even a “Special Slumber Crib” that could “be placed in single rooms to keep tiny travelers safe and comfortable.”

Additional cars for the Baltimore & Ohio, Missouri Pacific, Northern Pacific, and New York Central came in 1958 and 1959. This included a through car running between Washington, D.C. and Texas via the B&O’s National Limited as far as St. Louis, and then on the MP’s Texas Eagle for the rest of its journey. On the NYC, the new Budd equipment operated on the road’s premier train, the 20th Century Limited between New York and Chicago, while the NP added the new equipment to its flagship North Coast Limited.

The Union Pacific took note of the new budget-priced accommodations for the Denver Zephyr and leased a pair of Budd-built 21-roomette sleepers from the Pennsylvania to compete with the new cars on the Burlington from October 1956 until April 1957, including painting them in UP colors and charging economy prices; one wonders how travelers that purchased conventional roomettes on the City of Denver during this time period felt about this.

In 1961, the NYC converted 10 of its postwar Budd 22 roomette sleepers into “Sleepercoaches,” with 16 single and 10 double rooms and then returned the original Slumbercoaches to Budd. To accommodate this configuration change, six of the single rooms on each side of the aisle were arranged in the same duplex/staggered arrangement as the original 24-8 Slumbercoaches, while the remaining four single rooms were on the main level (two on each side of the aisle) along with the doubles.

In fact, the double rooms occupied the same space as the roomettes they replaced, albeit with an upper berth added; the four main-level singles had the space of a roomette, but with a narrower bed. As a result, savvy frequent NYC passengers traveling alone quickly learned to request singles 2, 4, 6 and 8.

In 1964-65, the NP acquired both the original four NYC Slumbercoaches and those from the B&O and MP, adding this type of equipment to its secondary train, the Mainstreeter. Interestingly, the joint B&O/MP service operated the last example of early postwar “through-service” sleeping cars between the East Coast and points in California and Texas.

By this time, with passengers deserting the rails in droves and, in particular, sleeping cars, a number of railroads elected either to price their remaining sleeper services using the coach railroad fare with an added space charge, or, in the case of the Seaboard Coast Line, offer space in the 16-duplex roomette, 4-double-bedroom cars (named in the “bird” series) acquired from the B&O as “Budget Room Coaches” on the Silver Star and Champion Florida services.

Presaging a practice that would be utilized by Amtrak, both the C&O/B&O, on the George Washington and the Capitol Limited, and the N&W’s Pocahontas (the railroad’s sole remaining sleeping car service by 1969) not only charged only the coach fare/space charge but also included dining car meals in the price.

Both the remaining factory-new Budd Slumbercoaches and the converted NYC Sleepercoaches were acquired by Amtrak after its formation in 1971, and these cars were later upgraded to be used with head-end electrical power as part of what Amtrak termed its Heritage Fleet of equipment predating the railroad’s formation.

On balance, while they couldn’t save the U.S. intercity passenger train, Slumber/Sleepercoaches probably helped slow the decline in a modest way, and since they were either relatively new when Amtrak began (or, in the case of the ex-NYC conversions, had been substantially rebuilt only a decade before), they had relatively long lives. As a result, several of the “24 and 8” Slumbercoaches have been preserved at a variety of museums, including one at the B&O Museum in Baltimore, originally assigned to the Columbian.

Would also point out that “Tourist Class,” a development of the 1880’s, was the primary mode of travel that made for the great California migration of 1890-1920. Santa Fe’s “Scout” and Union Pacific’s “Challenger” were composed largely of tourist sleepers.

… [Just perhaps the “Challenger” name that present day folk so associate with the big steam locomotive was sourced from somewhere else? And then there’s the UP’s “Challenger Inn” at Sun Valley ca. 1936.

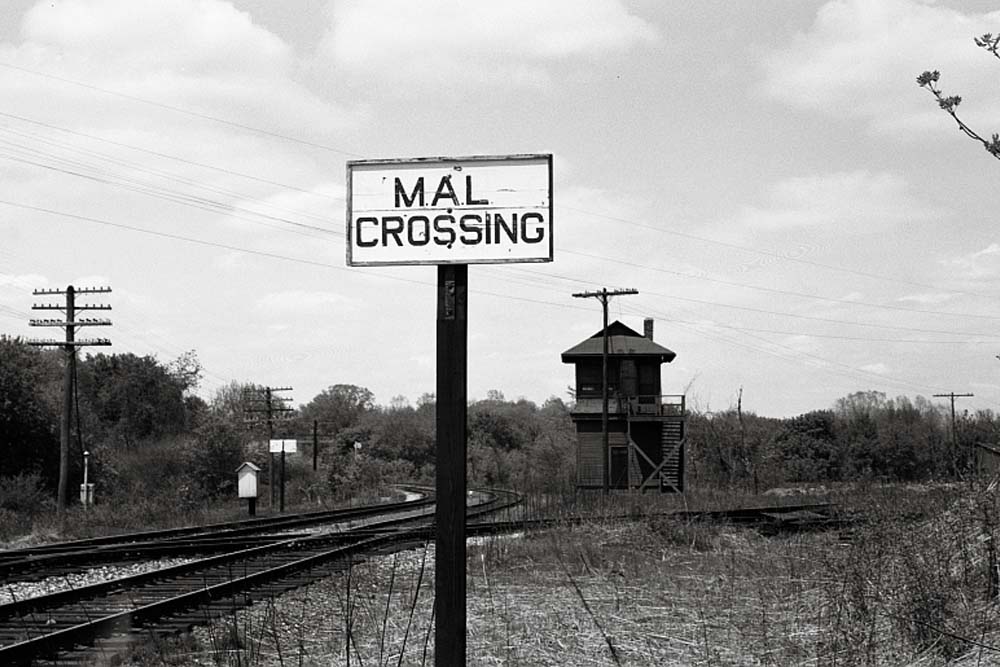

Your 1969 George Hamlin photo is NOT of a Slumbercoach! That’s a Budd built Pullman, 1954, with 16 duplex roomettes and 4 double bedrooms. Please do your research … The B&O was indeed an early operator of Budd’s 8 double room, 24 single room cars. M. Zega