U.S. railroads introduced long-haul luxury coach trains in the 20th century to attract a more budget-conscious traveler.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the worst of the Great Depression in the U.S. was over, and railroads began to invest in new passenger equipment; both new diesel motive power, and a radical new format for passenger cars, in the form of “streamliners.”

Initially, this effort focused on short-haul/regional day trains. By the latter years of the 1930s, the trend began to include long-haul, all-Pullman flyers, including the Santa Fe’s initial single-trainset Super Chief, as well as the Pennsy’s Broadway Limited.

In 1938, the Santa Fe brought forth a Budd-built coach streamliner as a companion on the Chicago-Los Angeles run and named it the El Capitan. In terms of equipment and service, this was both a revolution and a revelation for coach service passengers; the Santa Fe proudly announced this as “America’s Only All-Chair Car Transcontinental Streamliner,” and at its inception, it had no competition.

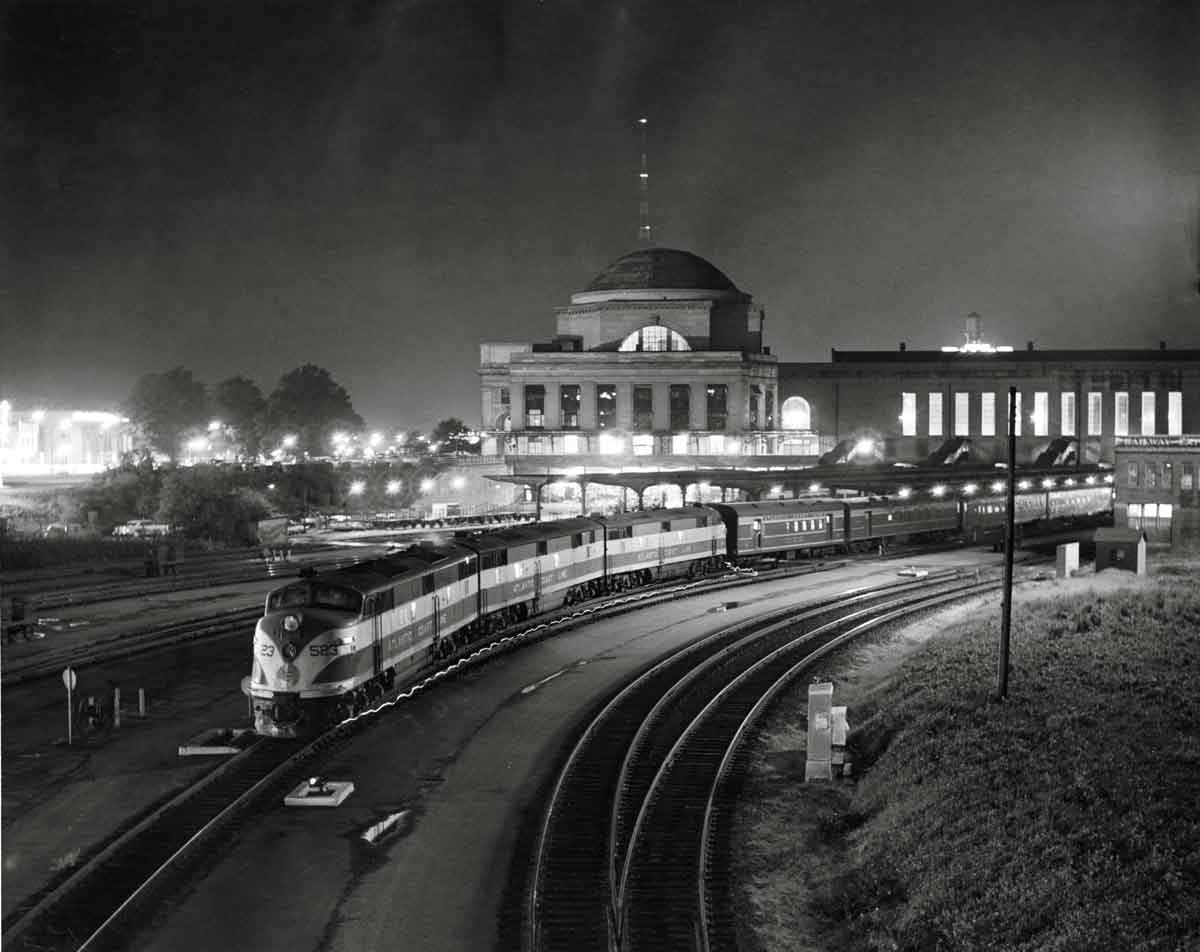

Others soon followed; for clarity, we’ll be examining those that included overnight travel, or were operated on daytime schedules that took 12-plus hours to complete. The Florida market was addressed in 1939 by the Atlantic Coast Line and the Seaboard Air Line, with, respectively, the Champion and the Silver Meteor, on the New York City-Florida run.

Both featured stainless-steel equipment by Budd that included baggage-dormitory facilities; a diner; an observation car; and several coaches. As a result, both the ACL and SAL were now operating newer, more glamorous equipment for their coach passengers than that offered to their Pullman/First-Class customers.

The Florida East Coast ordered two additional sets of equipment that were identical to the Champion’s. One set formed the third set of equipment for the Champion, in conjunction with the ACL, while the other provided a daily Miami-Jacksonville service on the FEC. In 1940, however, this equipment was shifted to become the Dixie Flagler, in the Chicago-Florida market.

There, it competed with a pair of new coach streamliners launched the same year: the South Wind, sponsored by the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Illinois Central’s eponymous City of Miami. Both had equipment like the ACL and SAL trains.

The Southern Railway added its Southerner, with stainless-steel clad cars manufactured by Pullman-Standard, on the New York-New Orleans route in 1941. In the same year, the New York Central streamlined its long-running Empire State Express, which entered service on Dec. 7, 1941 — Pearl Harbor Day.

This train operated beyond New York State, with its consists being split in Buffalo, New York for service beyond to Cleveland, Ohio, and Detroit, Michigan. Westbound from New York City to Cleveland took about 12 1/2 hours; reaching Detroit required an additional 60 minutes.

Although the Empire State did include parlor cars, its coaches were more numerous, and the observation lounge car was dedicated to the coach passengers; people in the parlors partook of refreshments in a separate car at the forward end of the train.

While not “streamliners,” both the Pennsylvania and New York Central introduced new, modernized (with features like reclining seats) “all-coach” trains in the hotly contested New York-Chicago market. Initially, at least the NYC’s Pacemaker utilized an open-platform heavyweight observation car, while the PRR’s Trailblazer featured a round-end observation rebuilt from a heavyweight coach.

In 1935, the Union Pacific launched its Challenger services to both Los Angeles and San Francisco using heavyweight equipment, to complement its premium, diesel-powered Streamliners, although this focused on “budget” sleeping car travel as well as coach accommodations.

During the war years, new equipment could not be added, even though traffic was booming. By the mid-1940s, however, the railroads anticipated still-robust postwar traffic levels, and viewpoint, ordered a great deal of new passenger equipment. While much of this was to re-equip existing runs, there were also new developments in the long-haul luxury coach sector of the market.

In 1946, the Louisville & Nashville launched a pair of all-coach streamliners, the Cincinnati-New Orleans Humming Bird, and the daytime St. Louis-Atlanta Georgian, the latter in conjunction with the NC&StL (Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis). In addition to upgrading the City of Miami, the IC also launched the new City of New Orleans between Chicago and its namesake.

One of the more interesting developments were the three trains, each by a different railroad, for fast daytime trains between Cincinnati, Ohio and the region including Washington, D.C., and coastal Virginia. Unfortunately, traffic proved to be significantly less than predicted. The Chesapeake & Ohio’s entry, known as the Chessie, never actually entered service; most of the cars were sold to other railroads.

The Norfolk and Western added a new coach streamliner known as the Powhatan Arrow between Cincinnati and Norfolk; it continued to be hauled by steam into the late 1950s, before succumbing to the passenger train malaise of the 1960s. Finally, the B&O converted heavyweight cars for its Cincinnatian between Cincinnati and Washington. While this enabled a noticeably faster journey than previously, low passenger loads caused the railroad to move this equipment to the Cincinnati-Detroit market early in the 1950s.

In the west, the Union Pacific re-purposed its Challenger service to the all-coach model for the Chicago-Los Angeles market, using equipment from its massive order of postwar streamlined passenger cars. The Southern Pacific launched the Shasta Daylightin 1949, operating between Oakland, California area and Portland, Oregon. The equipment had large windows to take advantage of the many scenic views on this route, except for the parlor observation, a pre-war car previously used in intra-California Daylight service.

As it became more apparent that rail passenger traffic in the U.S. was declining, there was a move to convert many of the all-coach trains to combined coach-sleeper runs. This occurred to the trio of Chicago-Florida services in 1949. The NYC’s Pacemaker and PRR’s Trailblazer, both lavishly upgraded with new equipment after the war, were combined with secondary all-Pullman trains by the early 1950s, as was the B&O’s postwar Columbian between Baltimore/Washington and Chicago. Similarly, sleepers were added to both the Humming Bird and the Georgian, with the latter becoming an overnighter between the Midwest and Atlanta.

Of course, the real problem was the declining number of travelers that continued to use rail passenger service of any kind, particularly for long-haul services. This became apparent during the 1950s and had become a major economic problem for the railroads by the 1960s. The 1970 arrival of Amtrak “cured” this problem, at least for the railroads, through a combination of a massive reduction in passenger train operations, along with removing what trains remained from the responsibility of the private railroad companies.

At the advent of Amtrak, essentially only one train, the IC’s City of New Orleans, bore a substantial resemblance to its genesis, although its boat-tail observation was gone by the late 1960s. An argument could be made that the Santa Fe’s El Capitan deserves mention in this category, particularly after the railroad re-equipped its coach flyer with “High-Level” cars in 1956 and invested in more of them in 1964. However, the El Cap had been combined with the Super Chief for many years by 1971, and thus no longer merited description as an “all-coach” train.

The B&O Columbian was combined with the flagship Capitol Limited not any secondary train. And, yes both NYC and B&O employed the fiction of listing “all coach” and “allPullman” trains in separate colums in the TTs with identical station times.

This story needs to extend the timeline to include the post-Amtrak services provided by the Southern Crescent and California Zephyr, both of which continued operation by the respective independent railway companies.

This article showed how much service we lost when Amtrak took over the railroads passenger service. However until recently Amtrak did try to keep long distance service relatively first class. Amtrak still puts more effort into their Northeast service and other state supported relatively short haul service. To fulfill their nationwide mandate they really need to get more cars, new or rebuilt to better serve the long haul customers they have. There are many small rural towns that need more cars particularly coach to serve their needs on the existing long haul trains. I have ridden on most of their long haul trains and was always suprized how many people used the train between the cities and towns between the end points.