JOHN W. BARRIGER III

One of the most peripatetic chief executives in railroading-he led Monon, P&LE, Katy, and Boston & Maine-was also one of the most sagacious. “J.W.B.’s” vision of the Super Railroad was the template for every Class 1 of the 1990’s.

RALPH BUDD

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR JR.

RICHARD M. DILWORTH

ANTHONY HASWELL

ROBERT D. KREBS

LOUIS W. MENK

ALFRED E. PERLMAN

D.W. BORSNAN – A Southern legend

Dennis William “Bill” Brosnan, Southern Railway’s sixth president (1962-1967), was a prescient despot. In mid-century, his vision, nerve, and drive transformed Southern into a lean money machine. Brosnan’s ruthlessness and disregard for the quality of life of his managers are legendary. Whenever Southern veterans congregate, you can hear them tell Brosnan stories with a mixture of awe and scorn.

We take for granted deregulation, unit trains, 100-ton freight cars, automation, and mechanization. All were unknown 50 years ago. But Bill Brosnan visualized, and, more importantly, implemented these and many other underpinnings of the modern rail industry, and at a time when such concepts were radical or heretical.

Brosnan was nothing if not controversial. He disdained mindless government bureaucracy, micromanaged his company to a fault, infuriated his rank-and-file employees, and controlled his managers alternately with fear and greed. He also helped fuel the meteoric growth of the South after World War II by coaxing a brilliant operating performance from a mediocre physical plant, and by scoring one marketing coup after another. Southern’s shippers and stockholders ultimately benefited handsomely.

Born in 1903, “DWB” grew up in Albany, Ga. After graduating from Georgia Tech, he joined the Southern in 1926, beginning in SR’s “boot camp,” the student apprentice (management training) program. Here, college graduates were expected to dirty their hands alongside section-gang laborers. To appreciate how the railroad works, you had to learn the fundamentals. And nothing is more fundamental than track.

From tamping ties, Brosnan climbed the operating ladder until by World War II, as a division superintendent, he had caught the eye of Vice President-Operations Harry deButts. A genteel Virginian, deButts continued to nurture DWB’s career, and on January 1, 1952, when deButts became president, Brosnan succeeded him as vice president-operations. From then on, the collaboration blossomed.

It was a hostile environment the railroads confronted in 1952: the Interstate Commerce Commission “protected” truck and barge companies from the “predacious” railroads, even though most railroads continued to lose freight to these competitors; postwar costs were rising faster than railroads could raise rates; industrial unions were growing more powerful, aided by 20 years of Democratic administrations.

The Southern faced an additional crisis: more than $65 million in 1906 General Mortgage bonds matured in 1956. With stagnant traffic and escalating costs, bankruptcy appeared likely unless something revolutionary happened.

And it did. In March 1952, Brosnan gave a stark message to his operating managers at an Atlanta meeting: Southern would survive only if the railroad changed fundamentally. He’d been planning how to do it for years, but couldn’t implement his vision alone. Appealing to each manager’s self-interest, he promised that, despite thousands of jobs to be cut, none would be those of supervisors or managers. Unsaid but implied: long hours of hard work and frequent relocations that would sacrifice normal family life.

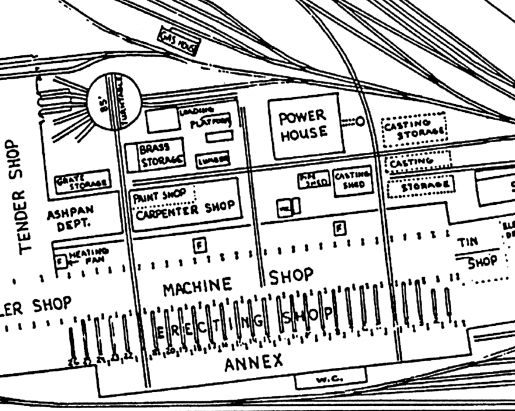

Brosnan’s goal was to cut operating costs. His strategy: do it with mechanization and centralization. Quickly and concurrently, he mechanized track maintenance, retired SR’s last steam locomotives, centralized car and locomotive repair, built automated hump yards, and consolidated operating regions and departments. If a machine to install crossties didn’t exist on the market, he and his tinkerers invented one and built it in the company shops.

Southern paid for all of its improvements, including the big-ticket capital items, with the savings from massive force reductions. In the decade of DWB’s vice-presidency (1952-1962), the number of Southern employees shrank from 37,000 to 18,000. But the result was solvency. On March 30, 1956, the 1906 General Mortgage was retired, solely from internally generated cash. DeButts and Brosnan were on a roll.

As the 1950’s waned, Southern’s operating efficiency improved, bringing faster, more-reliable freight service. In fact, Southern was one of the few roads to report better results in the second half of the decade than the first. But better operations alone couldn’t curtail the truckers, especially unregulated “gypsies” who fell beyond the scope of the ICC.

DWB knew that Southern’s potential remained largely untapped, so he fought back on several fronts. He sought lower rates for freight shipped in new 100-ton cars. He inaugurated unit coal trains, boosting locomotive and car utilization. And he planned to acquire railroads in the South with great industrial development potential and good on-line traffic.

As Brosnan succeeded deButts as president in 1962, his focus gradually turned to marketing. He envisioned growth only if railroaders truly understood the business of their customers. The marketing organization subsequently developed by his lieutenants hired specialists in different commodities from outside the company, a radical departure for the promote-from-within Southern. New freight cars ranging from Big John jumbo covered hoppers to the Quad Pod experimental dry-bulk carrier were designed with the same creative fervor as the new track machines 10 years earlier. Some ideas succeeded, some didn’t.

Big John, the aluminum 100-ton car that revolutionized modern grain handling, succeeded too well for the ICC, which denied Southern’s bid to haul grain from the Midwest to the Southeast at half the boxcar rate. After four years of deliberations, 13 hearings before Federal appellate courts, and two trips to the U.S. Supreme Court, Southern won-the first domino to fall on the path to deregulation 15 years later.

Among company men, Brosnan was both respected and feared. His capricious firing and rehiring of managers was legendary. He was the master of the stretch goal, demanding new machines or services in absurdly short time frames. More often than not, his managers remained loyal and came through for him. DWB would have had far fewer triumphs but for the loyalty and quality of key people. Two who played critical roles were Bob Hamilton, a crusty automotive engineer who helped design many of the new machines and later organized the unorthodox marketing department; and Stanley Crane, an R&D guy with a superb intellect who later became Southern’s eighth, then Conrail’s second, president.

In his own way, Brosnan recognized the sacrifices he demanded of his managers. For example, he improved retirement and other benefits, organized the Southern Wives Club (a support group for “railroad widows”), and raised managers’ salaries each time the Brotherhoods won a wage increase, and by a higher percentage.

If Bill Brosnan were here today, he would probably view railroading with mixed feelings. He would rejoice in the industry’s deregulation, its superb physical plant, its two-man train crews, and the health of Northeastern railroads. But it would drive him nuts to see how large and unwieldy the big carriers have become, how difficult it is for them to execute the fundamentals, and how long it takes to implement new technology. Come to think of it, a little of that Brosnan urgency, creativity, and vision right now wouldn’t hurt a bit.

I became an 19-yr old employee (agent-telegrapher) of the M-K-T in Oct., 1965, and sometime shortly thereafter, had a chance encounter with Mr. Barriger that lasted all of fifteen minutes as he entertained my impressions of the railroad and its possibilities. About one month later, I entered the Army and ultimately ended up in Alaska, near Anchorage, where I found a home on the Alaska RR.

I corresponded with Mr. Barriger a few times and told him about my travels on the ARR and the conduct of operations and he was sufficiently interested to ask questions about the traffic, motive power, and operating conditions in the dead of winter.

To my surprise, sometime in March, 1967, Mr. Barriger came to Anchorage with A. Schaefer Lang to inspect the Alaska RR and, having gotten my military address and telephone number from my parents in Dallas, invited me to have dinner with the two of them the evening before their tour began. During the dinner, both men plied me with questions about the property and what I thought could be done to improve operations: new power, freight service, trackage and siding improvements, communication improvements, and so on.

Knowing the property as I did, having spent almost all of my time away from the Army in the dispatcher’s office, I offered few suggestions because the ARR was a ward of DOT and dependent upon government funding. Regardless, I was certainly made to feel very welcome by both men and much railroading was discussed in my presence.

Later, in July, 1967, I came to Dallas for thirty days leave and had advised Mr. Barriger that I would enjoy visiting him at some convenient time. To my great surprise, Mr. Barriger invited my father and I to have breakfast with him on a Company business car spotted adjacent to Dallas Union Terminal North Tower during the second week of my leave and again, a few days before I was to return to Alaska.

Mr. Barriger made a lasting impression on me not so much as a railroader but as a man who welcomed the knowledge of others as well as sharing his knowledge.