The end of the 19th century marked the beginning of a conservation movement in America. Naturalists and environmentalists lobbied the United States government to set aside vast areas of wilderness in the American West as national parks. Growing public awareness and support for the idea prompted Congress to pass the National Park Service Act, which created the National Park System in 1916.

American railroads played an active role in developing and publicizing the country’s national parks. They built branch lines, constructed opulent hotels, arranged package tours, and marketed the parks to vacationers and long-distance travelers – all of whom would of course take the train to reach these sought-after destinations.

Northern Pacific takes the lead

The history of the western railroads and national parks can be traced to 1870, when Henry Washburn, Surveyor General of the Montana Territory, led an expedition to an area near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Surrounded by high, yellow rock cliffs, the area was known as the Yellowstone region, named by the Native Americans who lived there.

One member of Washburn’s expedition, Nathaniel Langford, went east to lecture on the group’s findings. While in Philadelphia, Langford met Jay Cooke, promoter and financier of the Northern Pacific Railroad extension project. Both men realized that the completion of the Northern Pacific would make Yellowstone readily accessible to tourists. Driven by the revenue potential of carrying vacationers to Wyoming’s unspoiled wilderness, the Northern Pacific was largely responsible for introducing legislation in Congress called the Yellowstone Park Act, signed by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872, which created America’s first national park.

Unfortunately for Northern Pacific, the Depression of 1873 temporarily halted construction of its main line across Montana. However, when the line was finally completed in 1883, it included a branch from Livingston to Yellowstone National Park.

Northern Pacific was the first western railroad to promote vacation travel to the national parks. As early as 1885, the company published an annual guidebook called Wonderland, filled with articles on train travel and western scenery. It was in those guidebooks that NP’s slogan “Yellowstone Park Line” originated.

Package tours

In the early 20th century, railroads took the lead in presenting the West to the American people, through their own publications, and in advertisements in national periodicals, such as Life Magazine, Look, and the Saturday Evening Post. Railroad artists did a masterful job of conveying the topography of the western landscape in colorful illustrations that brought out the land’s natural beauty and abundant resources.

Many railroad-produced western travel guides were targeted to East Coast residents, who for years had enjoyed journeying to Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains, Niagara Falls, and the Hudson River Highlands. The guides advertised package tours that combined visits to national parks with luxury rail travel in Pullman sleepers. For a fixed price, travelers bought a complete vacation, with reserved accommodations on and off the train, and guided tours of all major park attractions.

Great Northern opens Glacier

A few hundred miles to the north of Yellowstone, the Great Northern Railway followed in rival Northern Pacific’s footsteps.

In the early 1900s, Louis W. Hill, son of GN founder James J. Hill, played an instrumental role in the founding and development of Glacier National Park. Louis Hill was proud of his railroad’s association with the park, and he personally supervised the building of two luxury hotels there, the Glacier Park Hotel and Many-Glacier Hotel.

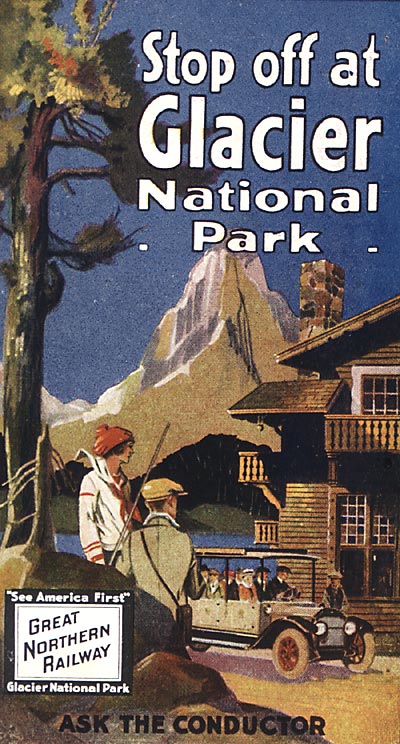

Great Northern produced a unique, pocket-sized travel brochure with the words “See America First” emblazoned on the cover. The brochure detailed the variety of multi-day tours and overnight accommodations available at Glacier Park, aimed at summer vacationers and transcontinental rail travelers wishing to make a brief stop-over en route. (Guests at GN’s hotels paid $1-3 extra for a room with its own bathroom facilities.) Great Northern trains stopped just south of the park entrance, within walking distance of the Glacier Park Hotel.

Great Northern also promoted the area in its annual calendars, with scenes of Montana’s Blackfeet Indians painted by German artist Winhold Reiss.

In 1960, with the automobile firmly entrenched as the family vacation vehicle of choice, the railway sold its Glacier Park hotels and buses.

Santa Fe’s trek to the Grand Canyon

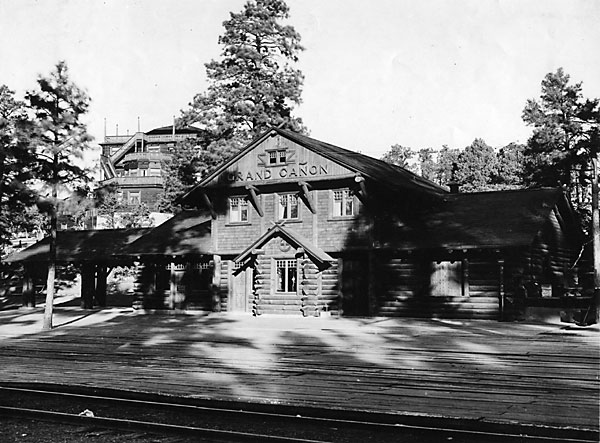

Another railroad with direct service to a national park was the Santa Fe, which built a 64-mile branch off its main line to reach the south rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona. The railway even had a streamliner named the Grand Canyon Limited, running daily between Chicago and Los Angeles, with through cars to the canyon via the branch line connection at Williams, Ariz.

In 1905, Santa Fe opened the magnificent, 100-room El Tovar Hotel at the canyon’s south rim. Built in the tradition of the grand European resorts, the hotel was constructed primarily of logs and boulders, and cost Santa Fe $250,000. Over the years, El Tovar grew into a community, with art galleries, a recreation room, music room, beautiful gardens, and of course a Fred Harvey restaurant.

“Santa Fe Pullmans to the rim,” was the advertising tag line that appeared in railway guidebooks, alongside photos of the hotel and the awesome Grand Canyon – 227 miles long, 18 miles wide, and one mile deep.

In the 1920s, travelers needed a bit of reassurance before stepping off a train in the parched, unsettled Southwest. Mountain and desert roads were unpaved, and automobiles were unreliable. Mindful of those concerns, Santa Fe’s partner Fred Harvey established Southwestern Indian Detours in 1926. Harvey hired young, college-educated women and trained them in the Southwest’s history, art, and geology. The Indian Detour Couriers were smartly dressed in long woolen skirts, Native American shirts, a silver Concha belt, and leather boots.

Harvey also hand picked physically fit young men, and trained them to drive the “Harveycars” (tour cars) in mountain and desert terrain. The drivers wore English riding boots, colorful cowboy shirts, and Ten-gallon cowboy hats. The women were paid $150 monthly plus expenses, and an extra $10 a month if they spoke Spanish. The drivers received $125 a month plus expenses.

Together, the Couriers and drivers escorted the rich, the famous, and the adventurous around Arizona and New Mexico, until the Great Depression ended most of the Indian Detours in the 1930s. Santa Fe ended passenger service to the Grand Canyon in 1968.

Union Pacific’s national parks tour company

In 1923, the Union Pacific Railroad opened a branch line from Lund, Utah, on its Salt Lake City-Los Angeles main line, to Cedar City, with the goal of promoting train travel to Zion National Park and Bryce Canyon in southern Utah, as well as the north rim of the Grand Canyon.

During the summer months, Union Pacific trains 309 and 310 ran between Salt Lake City and Cedar City, carrying through Pullman sleepers off the Los Angeles Limited.

About the same time the spur was built, UP formed a subsidiary bus and hotel management company, the Utah Parks Company, which built hotel facilities and offered tours of the three parks through a concession agreement with the National Park Service. From the Cedar City depot, Utah Parks took vacationers on escorted “All-Expense” tours in a fleet of buses with rollback tops.

Union Pacific advertised Utah’s national parks in public timetables, travel brochures, and nationwide magazines. “Never before have you enjoyed a vacation trip which was so free from care and travel details!” boasted a brochure from 1931. Many of the railroad’s well-publicized ads featured full-color interpretations of Zion and Bryce, as well as Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Geyser.

Union Pacific also sponsored tours to Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park, and Yellowstone, where passengers enjoyed a meal at the railroad’s dining lodge, located at the park’s western entrance. Branch lines in eastern Idaho reached the West Yellowstone, and the Grand Tetons at Victor.

In the 1920s and 30s, Union Pacific and partner Chicago & North Western produced beautifully illustrated travel books entitled Summer Tours. Those vacation books were some of the first to feature full-page color maps and photos. Escorted package tours ranging from eight to fourteen days offered travelers the chance to visit parks, wilderness areas, and cities throughout the West, the Pacific Northwest, and Alaska. In 1937, an all-expense, 14-day C&NW-UP tour of California cost as little as $211. “So promise yourself this vacation treat – and go this summer,” urged the brochure.

Union Pacific ended passenger service to Cedar City in 1958, no longer able to compete with the interstate highways that carried family cars to the once-inaccessible parks. Unable to find a buyer for its subsidiary, UP donated the Utah Parks tour operation and facilities to the National Park Service in 1972.

Southern Pacific in the Golden State, Burlington in Wyoming

In California, Southern Pacific trains brought passengers to Yosemite National Park, where they could experience the grandeur of giant Sequoias, waterfalls, and the magnificent high county of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. SP published Sunset magazine, which ran descriptive articles on the Yosemite Valley and other western vacation areas served by Southern Pacific.

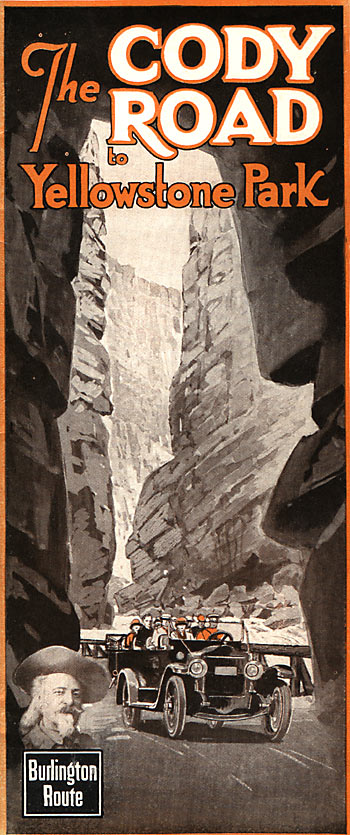

Not to be outdone by other railroads, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy published a 1937 guidebook titled The Cody Road to Yellowstone Park. The Cody Road was 90 miles of epic, mountain motor highway constructed from Yellowstone Park to Cody, Wyoming, home of Buffalo Bill. The brochure, naturally with a photo of Buffalo Bill Cody on the cover, boasted, “The Cody Road has no equal scenically, no parallel physically… crossing the wild country… spectacular in its colossal grandeur.”

Escorted four and-a-half-day tours to Yellowstone included a stop at Burlington’s Inn at Cody, adjacent to the railhead of its branch line serving the city.

Credit must be given to the visionary railroad men who encouraged train travel to the western back country that became part of the National Park System, and also to the many railroad artists who designed the colorful brochures that told the story of the national parks in words and pictures.

Today, you can still ride Amtrak trains, and trains operated by tourist and commuter railroads to many of the national parks so fervently promoted in the early days of rail travel. For a complete list, see the February 2001 issue of TRAINS magazine.