It was in this dark era that the Pennsy acquired its first 2-8-0 Consolidations that became know as the railroad’s H3 class of locomotives. The first of these rolled out of the Pennsy’s Altoona shops in 1885, and in the coming decade others followed from construction facilities in Juniata, Pa., and Fort Wayne, Ind., as well as from Baldwin Locomotive Works. According to a 1946 article in Railroad History, upwards of 870 H3s (in all sub-classes) were built, 430 of them in the style of the original H3.

The H3 locomotive proved to be a versatile and effective steamer. Its 57-ton weight and compact 50-inch drivers ensured that the H3 could operate with great freedom over the Pennsylvania and its associated lines. Indeed, in 1892 an H3 set a record of sorts, hauling a 40-car trainload of grain from Chicago to Philadelphia, helped only by pushers to cross the mountains near Pittsburgh.

Just how long did this adventure take? A mere 4 days, 6 1/2 hours!

The H3s served out their life on the Pennsy, and in time newer generations of locomotives bumped them from the roster.

In the late 1930s, H3 no. 1187, previously sold to a quarry in Pennsylvania, was rediscovered. The Pennsy bought it back and restored it for display at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. After the fair closed, the locomotive was stored for decades with the railroad’s so-called historic engine collection in Northumberland, Pa. In 1979 the Penn Central Corp. donated the H3 to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania.

The model

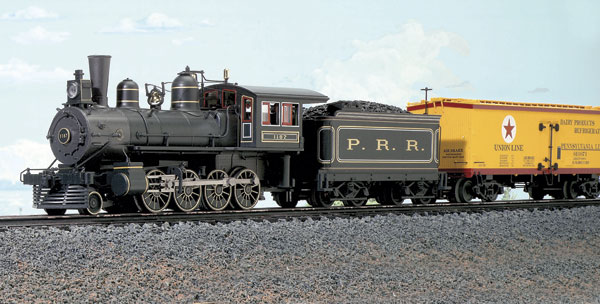

You’d be hard pressed to find a more distinctive die-cast metal O gauge locomotive than the MTH Premier line H3. Locomotives developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries stand out in appearance from those of the Civil War era and from those built during the final decades of the steam era.

The scale-sized MTH model measures approximately 151/2 inches long (approximately 68 feet in scale) from the end of the tender frame to the tip of its horizontally ribbed “cow catcher.”

Above the cow catcher is a scale-sized dummy knuckle coupler, with a chain attached to an uncoupler arm. The top of the pinot bar has a safety tread pattern (I’m not sure if this would have been used in the 1880s). Wood-grained steps are located on both sides.

The smokebox face and sides are filled with rivet detail. A number plate is placed centrally on the locomotive’s nose and a grab iron arcs over the top of the smokebox door. Separately applied grab bars and stanchions also are on both sides of the smokebox as well as along the flanks of the boiler. On top of the smokebox are an oil lamp (Edison’s light bulb was only six years old when the first H3 was built) and a smokestack that resembles a blunderbuss that the Pilgrims might have used!

Along the boiler, a thin, delicate pipe runs to the top of the steam chests. Above, two lanyards run from the bell bracket to the cab, and another runs from the whistle lever to the cab. The boiler itself has cast-in boiler bands and add-on pipe detail.

Tipping the steamer on its side, you can see rivet detail on the base of the firebox and more add-on pipes.

The cab is attractive, with side windows that slide open and shut. In true “nobody knew any better” fashion, the engineer and fireman practically sit within the top of the firebox. Indeed, in the real world it might have been easier to climb into the cab through its windows than from the opening at the rear.

To add to the insanity, the locomotive’s gauges were placed in the middle of the top of the firebox, so the engineer would have to lean over to read them. Suffice it to say, as time passed, locomotive designers did get smarter.

The tender is just as attractive as the locomotive and features a “real chunk” coal load and finely crafted safety tread and rivet detail. There is an add-on hand crank for a brake at the front. There also are brake chains on each of the tender’s die-cast metal truck sideframes.

Also of note is the pipe for adding water. If you open the hinged lid and look down, you’ll see a cast-in debris screen at its base.

Hinged boxes are on either side of the coal load. Under their lids are slide switches for two-rail/three-rail operation and polarity, should you choose to run your locomotive on scale two-rail track. For two-rail operation the pickup rollers underneath the locomotive frame can be removed with a screwdriver. Volume and smoke controls are under the tender.

The painting and decoration are up to MTH’s typically high standard. The locomotive and tender are Brunswick green, and the smokebox and the bottom of the firebox are dark gray. Typical for 19th-century locomotives, there is pinstriping everywhere. The cab, tender, and parts of the locomotive are trimmed in gold and white, and all of the window panes are trimmed in red. Even the drivers feature gold highlights, and the spoke stripes are continued across the counterweights.

The “P.R.R.” on the side of the tender looks a little bit supersized compared to the prototype photo taken at the 1939 World’s Fair, but MTH may well have some additional information on the size of the locomotive’s lettering.

On the test track

Tucked neatly inside the boiler is a horizontally mounted can-style motor. Power is sent through a gearbox above the second set of drivers, and then to the other geared axles. If you look closely above the third set of drivers, you can see a black-and-white band of tape affixed to the motor’s flywheel for ProtoSound 2.0 speed control.

The front and rear drivers are flanged, and there are traction tires on the two rear wheels. The tender has a coil coupler. The locomotive has two power pickups spaced 31/2 inches apart, and we encountered no slow speed stalling on track switches.

The speed range for our test sample was 1.96 scale mph to 74.7 scale mph. Drawbar pull for the 5 pound 5-ounce locomotive was 1 pound 15 ounces.

During operation I got a kick out of the locomotive’s handy size. It’s a little guy, especially when placed next to a Northern, Challenger, or even a scale-sized Pacific on my layout. Heck, in overall mass it’s even a tad smaller than Lionel’s undersized postwar Turbine locomotive. Its drive wheels give the locomotive a pretty distinct look as well.

On our test track and on home layouts, the H3 Consolidation moved as smoothly as an Olympic skater. Two things were apparent only when the locomotive was under way. First was the mesmerizing back-and-forth action of the combination levers, moving the valves in and out of the steam chests. On most of the models of modern steamers I’ve seen, this action tends to get lost in the blur of more elaborate running gear.

Second, I thought the view underneath the boiler was pretty neat. From the correct angle, you can look beneath the boiler and watch the inside of the opposite drive wheels.

This is a neat effect as the spokes rotate in and out of view, allowing you to see the inside surface of the counter weights and the tops of the opposing side rods. Most models of larger, more modern steamers with their big round boilers don’t offer this view.

As is the norm, all ProtoSound 2.0 functions worked as advertised when operating the locomotive using MTH’s Digital Command System. The model’s sound reproduction is excellent, and for intangible reasons I felt that the sound from this model was slightly better than that of other ProtoSound 2.0 locomotives I’ve tested. I chalked it up to the lack of collateral mechanical noise (compressors, steam blow-offs, etc.) that you’d experience with, say, a 4-8-4.

The only time I winced was when the whistle tooted. And I mean “toot, toot,” not “whoo, whoo.” But it is one more thing that helps give this Consolidation steamer a unique personality.

Amid legions of Pacifics, Hudsons, and articulated locomotives, the petite H3 stands out. Interest in trains from the Gay Nineties to the Roaring Twenties may be a trend to watch.