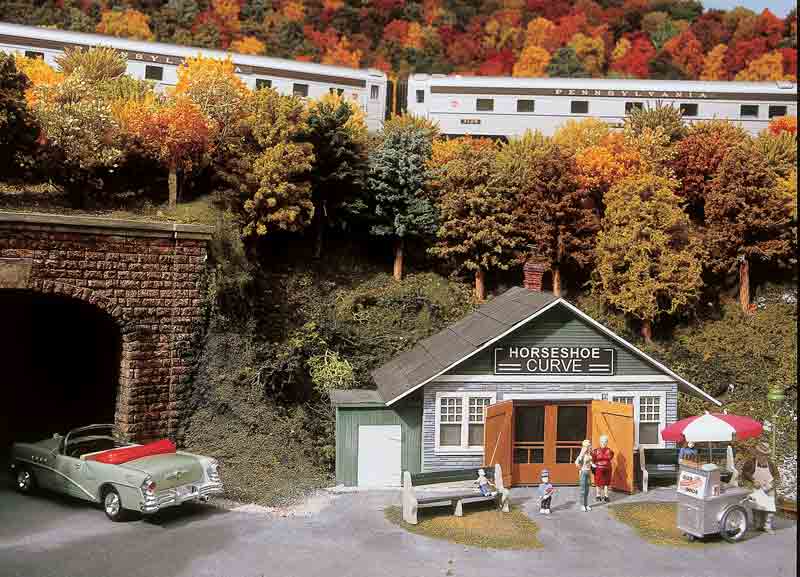

Scale model railroaders have long known the challenges and pleasures of building layouts based on specific sites. Many focus on “hot spots” like Cajon Pass and Tehachapi Loop in California, Sherman Hill in Wyoming, and Horseshoe Curve in Pennsylvania – places celebrated for their geography and the variety of trains that pass through. Count O gauge enthusiast Don Williams, whose layout models the famed Horseshoe Curve, among the hot-spot fans.

Growing up in Altoona

Horseshoe Curve is a section of the former Pennsylvania Railroad’s main line, part of the bustling railroad scene in the central mountains of the Keystone State. The curve’s four tracks, hemmed in by a wall of rock and ravines, follow a semicircular path up a 1.75 percent grade to escape these natural barriers. Today, Horseshoe Curve belongs to the Norfolk Southern.

Don’s family has ties to the area, and he spent part of his youth in the nearby town of Altoona. It’s no surprise that he dreamed of his own Horseshoe Curve.

“I spent my earliest years in Altoona,” Don begins. “My parents were married there and lived next door to my grandparents. One of my uncles had a church just down the road in the 1940s and ’50s.”

The sights, sounds, and smells of his youth stayed with Don. Occasionally, he tried to create in miniature what had impressed him years earlier. With his son Mark he built a few HO scale layouts modeled after the Pennsylvania Railroad.

But as nice as those layouts were, they didn’t satisfy Don. Something was drawing him to the latest releases in O gauge from Lionel and MTH. Don liked the larger trains and decided his next layout had to be O gauge. He also decided that he was not the guy to build it.

“I had enough hobby experience to handle the track,” Don states, “but the free time wasn’t there. This layout had to be done long before I retired from advertising!”

Don talked with friends in the hobby about the craftsmen who construct layouts for a living. He learned of Michael Hart’s Miami-based firm, Scale Models, Arts, and Technologies Inc., and visited its website (smarttinc.com).

Michael and his SMARTT staff have jumped into the elite of builders in recent years. [Two of their layouts appeared in the May and December 2002 issues of CTT. – Editor]

Michael and Don conferred regularly, mainly about the size and configuration of Don’s train room. They settled on an L-shaped track plan that covers an area approximately 26 by 45 feet. Later they got around to discussing roadbed (3/4-inch Homasote), track (GarGraves and Ross Custom Switches), and accessories (postwar and modern-era Lionel).

More important, Don discussed with Michael his goals for the layout. Not until he sensed that Michael had a genuine “feel” for Altoona was he ready to entrust construction of the railroad to SMARTT.

Researching the prototype

If, like Don, you intend to model a specific area, you need more than memories and a pile of track and lumber to start. Don recommends a visit to the area. “You’ll first be amazed at how much has changed,” he laughs. “Then you’ll be surprised by how many prominent features have survived.”

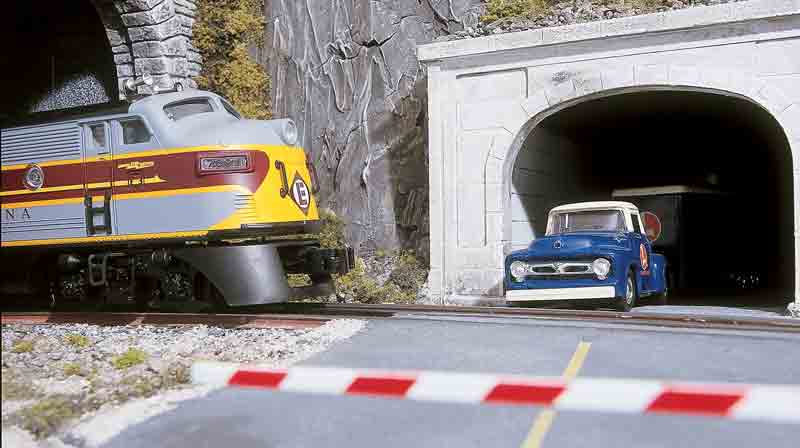

Horseshoe Curve, lauded as a monument of railroad engineering, still stands. Pennsy K4 4-6-2 Pacifics and M1 4-8-2 Mountains no longer pound the high iron. In their place Don discovered Norfolk Southern SD90s and Dash-9s, along with an occasional unit still wearing Conrail blue.

Walking through downtown Altoona, Don came upon a few of the landmarks from his youth. Most of the locomotive-servicing facilities used by the Pennsy and Penn Central are gone, but a handful of stores and cafes remain.

The next step, according to Don, involves reinforcing first-hand knowledge with secondary sources. Vintage photographs published in books and magazines capture many of the neat details that inevitably fade from mental images. Accounts from the past, especially those written by travelers, provide more information.

Among the best sources are commercial videotapes, especially those containing film shot at different times. They often provide views of structures, landscape, locomotives, rolling stock, and more.

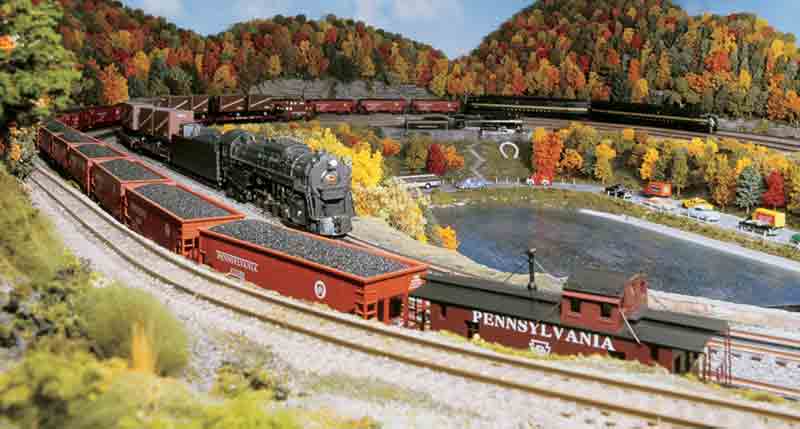

Armed with adequate research material, it was time to select what to include on the layout. For Don, Horseshoe Curve and the reservoir adjacent to it were essential. So were the forested hills above and beyond the tracks. The main feature, he explained to Michael, had to be a four-track main line characterized by the smooth, sweeping curve of the prototype.

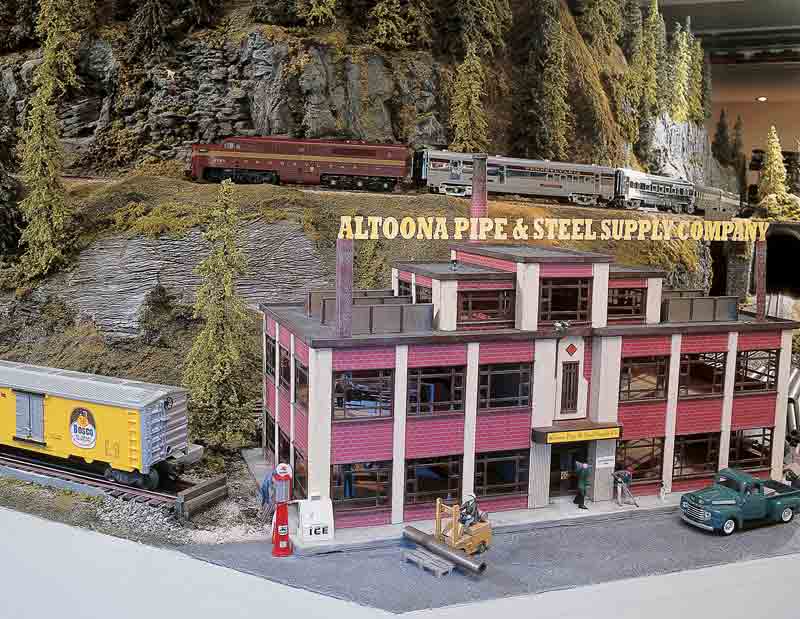

What about Altoona? Don knew he wouldn’t be able to duplicate every street corner and vacant lot in town. But he insisted on allocating plenty of space on the layout for an urban area that suggested the feel of life there.

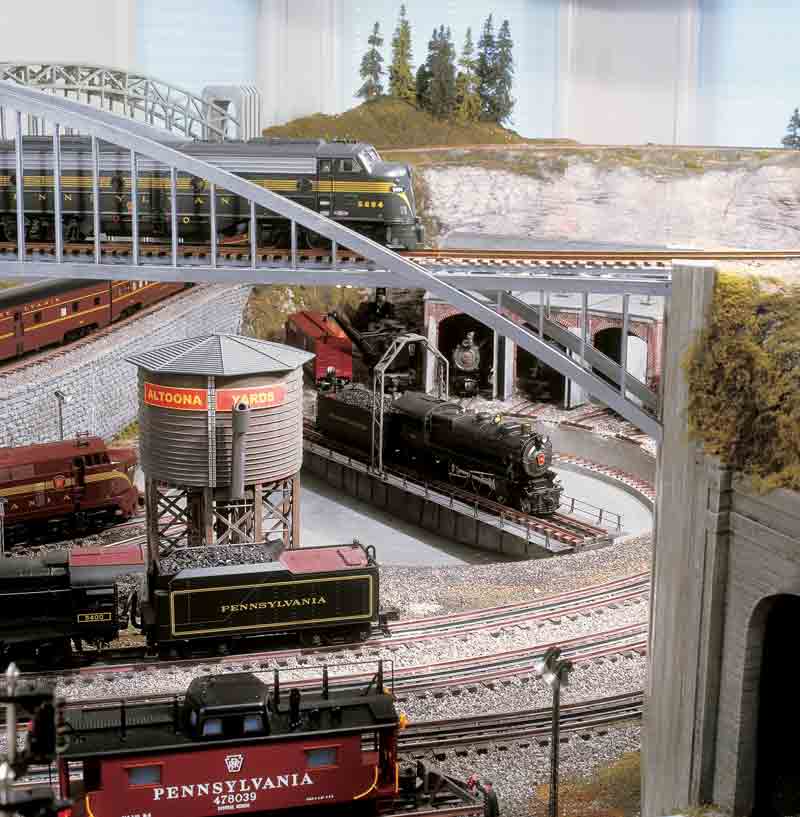

At one end of the layout the SMARTT crew proposed a rail yard and locomotive-servicing area. Don specified a roundhouse and turntable, water tanks, and the “car shop” where his father worked following World War II, all in what he knew would be one of the busiest and most entertaining parts of his layout.

Don suggested that Michael and his staff bring the main lines through town and have sidings branch off from the yard. On those tracks, engineers could assemble freight trains by coupling their locomotives to the strings of coal hoppers and Tuscan red boxcars. Not far away the builders planned to install an impressive passenger terminal.

From the yard area, the rail lines would merge into the main lines that go west along a river that meanders below the center of town.

When offering tips on the look of central Altoona, Don wanted the storefronts abutting the landscaped mountains to remind him of the days when he walked downtown to get his hair cut, buy a Hershey bar, or select another Lionel model.

Fortunately, portions of the old neighborhood still exist, including the house where he once lived. Between what Don remembered and what he saw on visits, he was able to help Michael create a convincing version of Altoona.

The SMARTT staff enhanced this urban scene with an array of die-cast vehicles heading east and west on a highway bordering the riverbank.

Hills, S gauge, and accessories

Outside Altoona, Don gave Michael liberty to improvise. Scenery reminiscent of the woods and rugged hills of the Appalachians and Alleghenies is among Michael’s trademarks. Besides adding realism to the scenery, these natural features serve to separate parts of the layout to convey a sense of distance.

Michael suggested having a single-track main line run beyond Altoona so trains didn’t seem cramped in the wilderness. The other lines are partially hidden behind and beneath Altoona, and there are also three hidden staging tracks directly beneath Horseshoe Curve accessed through tunnel portals.

Another challenge that Don laid before Michael was the need to incorporate an S gauge line on what was otherwise strictly an O gauge affair.

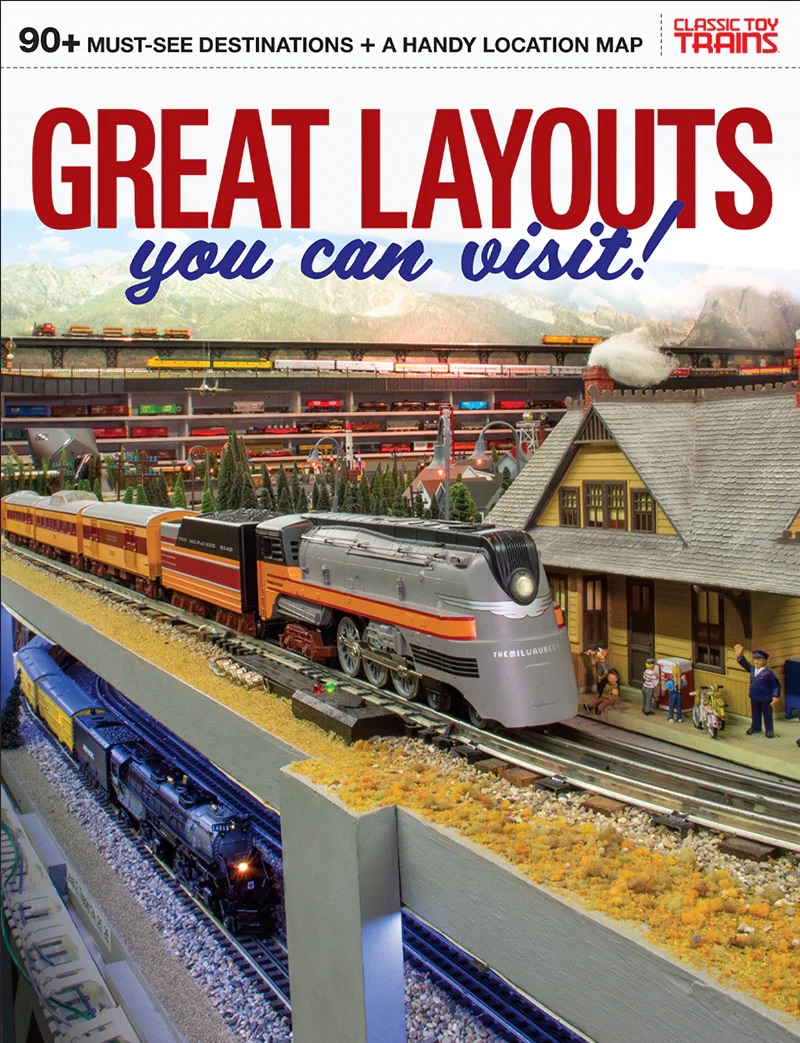

The SMARTT team installed S gauge track on the hills above and slightly beyond the O gauge main line. This arrangement makes the mountains seem larger while enabling Don to run new American Models and vintage American Flyer equipment.

Speaking of vintage, did I mention that Don has a passion for some of Lionel’s postwar accessories? He wanted Michael’s crew to include various toy-like freight loaders and bridges on a railroad that was fast becoming the epitome of hi-rail modeling.

The builders shrugged their shoulders and started discussing possible courses. The key to their success was Don’s willingness to allow his accessories to be slightly modified and weathered so they would fit in better on the layout.

Soon Don’s nos. 97 coal elevator, 362 barrel loader, and 456 coal ramp sported coats of rust and grimy black paints that transformed their appearance. As important in working these Lionel favorites into the outskirts of Altoona was designing foundations for them and adding signs. Once completed, they looked just right amid the tired houses and gritty factories.

When to compromise

Don’s decision to place the reworked accessories in a key part of his layout brings up two related and important points about planning a layout. These ideas apply whether you’re designing a hi-rail empire or something smaller and less demanding.

First, don’t worry about duplicating in miniature every aspect of a hot spot – aim, instead, to give a general view and impression of the area.

Second, feel free to include features that bend the limits of realism yet still fit in with the level of modeling.

For example, Don knew he didn’t have enough space to model the immense railyard, so he was content to suggest its size and complexity. The same approach influenced his efforts to capture the look of Main Street.

While the size and scope of a Horseshoe Curve or Cajon Pass layout may not be in the cards for everyone, a little research and some give-and-take when modeling a real-life scene allow anyone to build their own “hot spot.”

I always like how S gauge is mixed with O gauge to create forced perspective. This layout is an example.

Very interesting stuff. Very inspiring, too. Mixing old and new, O and S, real and imagined opens up any number of possibilities. This demonstrates that the results can be truly outstanding.