To elevate or not to elevate? That is the question we address while deciding on a style for our garden railway. Proponents of the “box” style like to raise the trains closer to view and say they don’t have to bend over so much, but it may surprise you to know that plenty of folks prefer to integrate the railway into their landscape. It may seem like a given that, without the box, it’s easier to build, but we still need examples of how to incorporate our trains into an interesting landscape. The gardeners in the following pages prove their “ground-level” railways are anything but flat.

Family thyme

When Barb and Jim Kimmel step out their back door in northern Ohio, a miniature world beckons like the one in Gulliver’s Travels. Neutral pathways of flagstone take them from one garden to another while similar boulders and ballast tie the beds together. Each area emanates a theme that is identified by a structure or simply a scale forest. Each thematic building’s landscape is fittingly attired in scale plant material. Their vacation spots have been transported to their backyard garden in memory of good times.

On the day I visited the Kimmels’ railroad, trains ran past the fish pond then took off for destinations unknown (photo 1). Barb had built a berm with gray boulders, juniper, and sedum, topped by a cut-leaf red Japanese maple, making a view-block of their house and the neighbor’s yard. She says it wasn’t planned as a barrier but my focus meandered from one colorful building and tree to the next, staying within the yard. The boulders blended with their gray house siding and a miniature gray grist mill. Carpeting the rocks, masses of tiny white flowers parted when the cable car arrived.

Across the pathway, also just off the back patio, a most soothing meadow of blooming thyme attracted me (photo 2). Unlike the bright scene across the way, soft pink blooms spread from the path to the lawn, getting a foothold between stepping stones. It reminded me of a trip to Arizona in the spring—the wide-open spaces and wildlife. The Kimmels’ exquisitely pruned miniature shade tree (Picea glauca ‘Conica’, Zones 4-8) sheltered the model of a mission-style adobe house. The old spruce looked as though it had been protecting this home for eons, while funneling 1:1 foot traffic around the scene.

A folded-dogbone railway in a modest-sized yard often requires two or more tracks to run parallel en route to the next return loop. Jim accomplished this by cutting into the lawn where a narrow bit of land carries trains to the other end of the house (photo 3). He edged the corridor with broad, flat stones that double as a “mow strip” for the lawnmower’s wheels. Jim’s grandfather was always showing him how to solve multiple problems with new ideas and home-made tools that exactly fit the need of the moment, a set of skills he frequently uses on the railway. It was in honor of his grandfather that the Kimmels named their line the Ross Herron Memorial Railroad—and because his grandmother wouldn’t allow her husband to be a locomotive engineer.

Safe passage

While raised-box gardens allow for visual proximity to trains, ground-level tracks invite you in for a multi-dimensional experience, where trains can surround the traveler. The first railway I built for my (at the time) very young grandson and me was raised (above a retaining wall) because we happened to have that scenario already built into our sloping yard (photo 4). No one told me it was for viewing only, so within the railway, I made clear pathways of pebbles, benches of split logs, and a gravel yard for young ones to sit and fill trucks with front loaders. A tiny lawn doubled as a farm field and airport for all to recline and get down closer to trains. The snow shed doubled as another seat. Photo-takers were appalled, but the rest of us were into it. Children, upon arriving, smiled to think that even they could enter the miniature town and push cars over the car bridge.

Brian and Shirley Wenn’s more sophisticated “come on in” railroad has room for sipping tea on a secluded patio or dipping toes in a rushing river (photo 5). In their No-Name Railroad of British Columbia, a hand-railed footbridge takes us over another branch of the river. Plant material helps to guide 1:1 traffic while providing scenery for the railroad. Far regions are raised somewhat on rock retaining walls. All in all, it’s a magical, park-like garden that allows both trains and humans.

In a rural New Hampshire town, Dave and Jenny Miller spend many summer evenings looking out of their back screened-in porch onto a lovely garden railway. When the weather is right for gardening or strolling, gravel-covered walkways blend with the creeping thyme and sedum planted for low groundcover (photo 6). Often the paths are indistinguishable from the lawns, parks, and meadows within the railway, but it’s all stepable. The obviously larger plants form the trees, around which we move. It’s a relaxed feeling, walking into their world, although the trains keep us alert.

As important as it is for us humans to safely get around in the garden railroad, the trains and track can benefit from protection from our big feet and outdoor issues, like erosion and settling. Gary Siegel firmed up his rough terrain with a concrete sub-roadbed (photo 7), enjoyed by guests of all kinds.

What do you like (or dislike) about your ground-level railroad?

Stan and Deb Ames

Chelmsford, Massachusetts,

Zone 5

Forest-floor railroad

A large railroad such as ours would not blend into the garden and woods if it were raised so, if we had to do it over, we would still build it on the ground. There are a lot of tradeoffs on ground-level vs. raised railroads. We use larger rail (code 332 has the highest rail profile) to prevent deforming when we occasionally walk on it. One downside is that bending over to uncouple trains, or getting down on our knees is more work as we get older.

When we started out, we read all the books and the approach described was to dig out a 6″ trench and use “bender board” to line the edges. Alas, “bender board” is a west-coast thing and not available in the east. Our first attempt, which we used for several years, was garden edging for the sides of the trench. The winter frost was not a friend. While garden edging works in the garden between two areas of dirt, the gravel ballast on one side and dirt on the other resulted in the frost raising the edging.

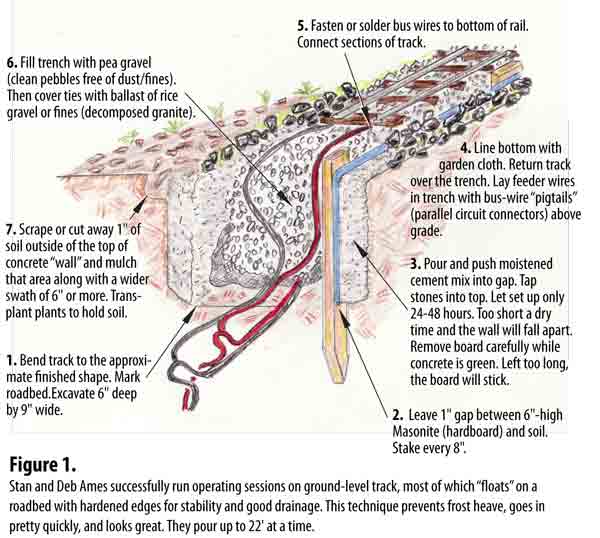

We’re not sure how we came up with the cement edging idea (see the steps in figure 1) but we had always liked the look of English gardens and we felt the rock edge blended more with the garden.

Solid-concrete roadbed is great in some places but not so good in New England, with frost heave. Also, wiring and changes to wiring are more difficult when you have a solid roadbed.

One side benefit is that, after a few weeks, the feeders tend to settle and keep the track firmly aligned. Heat and cold cause the ends of the track sections to move slightly but the center of each section with the feeders never moves, holding up well over many winters. In sunny areas, moss does not grow but, in the shaded areas, moss will start growing in a few years, or faster if some is placed there as a starter.

Alternatively, we will add pea stone first, leaving places for the feeders to be installed, then add pea stone later to the areas where the gaps are. At other times, all track is installed and wired first, then we add pea stone.

Richard Friedman

Sacramento, California, Zone 9

Raising possibilities

I’ve got a ground-level railroad. When I started it, that style was almost the only thing I had seen. It also made sense for a number of practical reasons: my yard was already flat; I was going to incorporate it into an existing garden, so couldn’t raise the rest of the yard; I avoided the expense of walls, additional dirt hauling, and tamping; and I wouldn’t have so much replanting to do. Over time, I’ve raised sections of it to improve the visibility of the far parts of the railroad. I’m now putting in a new spur and will put it up on a short section of concrete blocks to reduce the slope without burying my established garden.