One approach, planting genetically miniature* plants, ensures almost no pruning for quite a long time but it can get expensive unless you propagate more new trees from cuttings. Gardeners with time on their hands employ a second, cheaper method. Once or twice a year they artistically sculpt dwarf shrubs, like boxwood and dwarf Alberta spruce, to open up and expose the trunk and branches. . .if they know how (“How to prune your dwarf Alberta spruce: Trimming established trees for a more scale appearance,” December 2009 GR).

The third option is topiary-style pruning—shearing the outer tips of all branches to create geometric pompoms, balls, lollypops, and cones, with or without visible trunks. Many of us successfully trim our trees as if they were topiaries and the shapes last for many years, if maintained. Here we’ll identify evergreen shrubs that respond well to this treatment and see how fellow modelers fit them into their railroad’s landscape.

An olde art

The art of topiary probably originated in Greece or Persia. In Latin, a landscape gardener is topiarus. Traditional meanings refer to the art of styling evergreen plants into geometric forms or animals, which result in a more formal look than tree-like pruning, as in bonsai. Through the ages, topiary has enjoyed varied fame. . .and notoriety. All it took was criticism by an English writer to erase the hobby from English gardens for a century or so. He complained that a boxwood pig looked more like a porcupine after a week of rainy weather.

About new growth

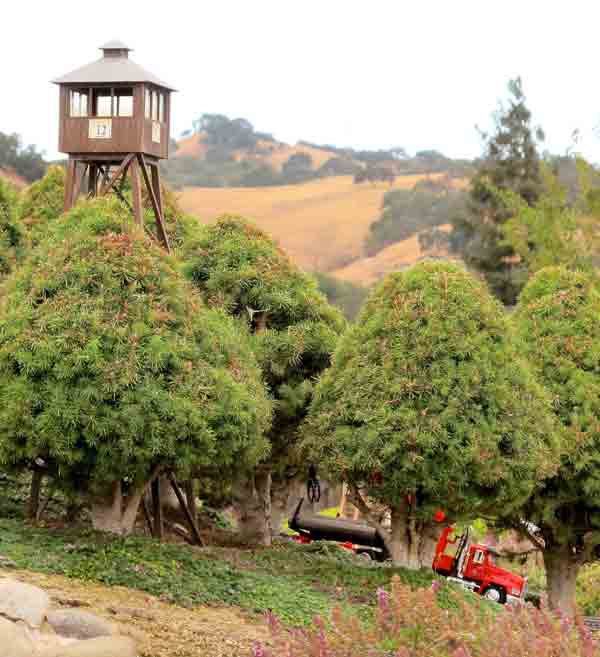

ne thing can be agreed upon: topiaries need regular maintenance. How regular depends on your choice of plant material. Check the tag or online forums (davesgarden.com) for information regarding expected growth. See the footnote on page 20 for the parameters of growth rates. For example, Gary Knoth prunes his dwarf trees in photo 1 twice a year. He and other gardeners use scissors, battery-powered reciprocating grass trimmers, electric hedge trimmers, or hedge shears with 6″ blades, held in both hands. Only the soft new growth is trimmed off.

Maintenance is relatively simple: merely trim a uniform length off the surface of the shape. If your tree arrives formless, you must establish your shape of choice, usually with hand-held pruning shears.

Photo 2 shows how new growth gets started after a haircut. The appearance of new branch tips can be attractive during this honeymoon phase. In fact, it’s best not to prune new growth early in the spring, when watery sprouts will be damaged and browned by cutting too soon. Premature pruning can “sap” a plant of life. By late spring, new growth has hardened and darkened to look more like the mature growth, and the sap is not flowing freely, so it’s safe to cut the tips.

Creative gardeners find other methods of pruning trees but there’s no need for the disposable-tree approach, in which gardeners yank out over-sized trees and replant with new, small ones. Maybe, after 10 or 20 years, if the growth rate is fast, this process is warranted. We’ve all seen hedges with large gray skeletal patches. Herein lies a potential problem with topiaries—shearing off all the existing and future buds. Most plants will only grow buds (new growth) near the tips. The hidden-from-sun recesses of topiaries will not initiate new growth or new leaves. Therefore, start your shapes smaller than ideal and allow for expansion each year.

Topiaries are fun

Remember why we got into garden railways? It’s easy to get sidetracked by the seriousness of taking care of living things. Then we set artificial standards for how real our trees “should” look. What you can’t see in photo 1 is Gary’s grandson, Lucas, helped by friends and members of the club, learning how to operate several trains on the railroad. In photo 3, Roger and Faith Clarkson invite the public into their backyard to share the fun. They need to keep trees manageable. Topiary-style pruning is relatively quick, compared to bonsai style.

Todd Brody (cover story, Dec. 2013 GR) enjoys planting amorphous shrubs and transforming them into scale trees with character (photo 4). Joe and Ann Mortillaro want to look out their window in all seasons and see the beauty and excitement of the railroad, which draws them out to their labor of love; one day they staked and trained a groundcover into a tree (photo 5). Dan and Katy Hill also started with a groundcover vine and fashioned a living arch (photo 6), as if covering a tiny trellis, because they could.

Nancy Norris

You can, too. Small-leaved plants can form living tunnels and miniature hedges (photo 7). Here’s an idea I’ve seen only once. Instead of shearing flat, geometric box-like hedges, a British railroader, Neal Ramsay (June 2009 GR cover story), sculpted his box-honeysuckle shrubbery into green mountains of peaks and valleys that grow right up to the track.

*The American Conifer Society has established standard labeling parameters for the landscape-nursery industry:

• Miniature plants grow less than 3″ per year and mature to 2-3′ in 10 to 15 years.

• Dwarf plants grow 3″ to 6″ per year and mature to 3-6′ in 10 to 15 years.

• Intermediate plants grow 6″ to 12″ per year and mature to 6-15′ in 10 to 15 years.

• Large plants grow more than 12″ per year and mature to more than 15′ in 10 to 15 years.

Gary Knoth

Morgan Hill, California, Zone 9

Fruitful forms

“Apple tree” cotoneasters (pronounced, ca-TONY-asters) are six to eight years old. I planted nine in a temporary area before I decided where the farm was going to be located. Two years later I transplanted them and a few did not survive, so I replaced them. I trim them in the late spring for shaping, and again just before our open house in August to remove any new growth. They have a fast-growing root system. Were I to do it again, I would plant them in their final locations and not plan on transplanting them. One of the original plants had such an extensive root system that I left it in place.

I purchased my dwarf Alberta spruces (photo 1 in “Greening. . .”) mostly from Walmart and Lowes at less than $4 each. For 10 years, I have shaped some of them to look like pine trees and allow others to take a ball/cone shape. I trim off all of the new growth with shears at the start of summer and do some shaping, which is the only trimming that has been required.

Richard Friedman,

Sacramento, California, Zone 9

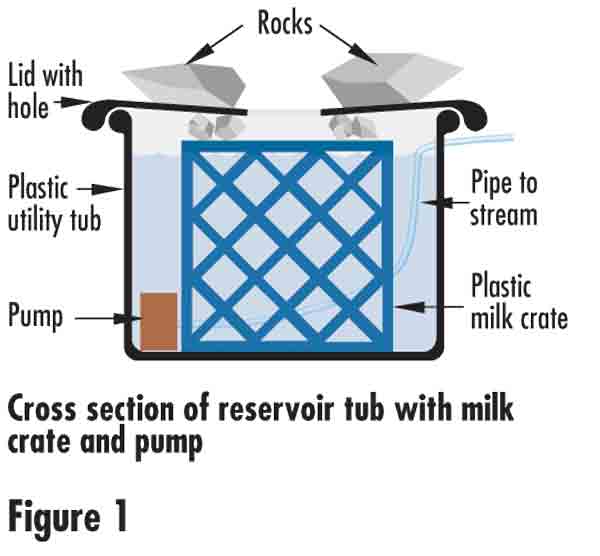

Mock tunnel

My mock orange tree requires constant pruning to keep it from overrunning that part of the yard. As it grew, it grew down onto the track and up through the bottom of the open trestle. I finally gave up. Instead, I built a “tunnel” of hardware cloth (1/4″ or 1/2″ metal mesh), draped a piece of tar paper over it, and put a portal at the mouth of my tunnel. Now, drooping branches of the mock orange drape over the tunnel and obscure most of the hardware.