Got a brown thumb? Need low, rugged groundcover? Here’s a botanical group of succulents with more than 400 varieties—sedums. Common names include “live forever” and “stonecrop” but most gardeners call them sedum (rhymes with “can’t beat ’em”). In this column you’ll see foliage colors that range like a rainbow, from red to purple and even black! Savvy railroad gardeners across the continent (USDA Hardiness Zones 3-11) demonstrate all sorts of uses for the sedum group.

Zero in on xeric

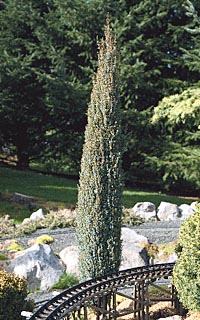

Big Sky is the name of the railroad in photo 1, as well as a cultural requirement for most sedums—a big, sun-filled sky! Tony and Joan Scheiwiller filled in the central, shadeless portion of their railway with six stonecrop varieties that bloom at various times in the summer. The tiny, rubbery leaves provide season-long color and fit into the Southwest theme. To help this theme, companion groundcovers, like the rosy hen-and-chicks (Sempervivum sp., Zones 2-11) and red creeping thyme (Thymus sp., Zones 3-10), blend visibly in harmony with similar-sized plants. The key to lasting success is that all plants in the same locale have similar growth needs—in this case, the genetic ability to withstand drought.

Most stonecrops prefer to grow in gravelly, sandy, well-drained soil so that succulent roots get air along with modest moisture. Surprisingly, sedums are relatively shallow rooted and easily pulled out if they approach the tracks. In photo 2, notice the water-filled foliage on Dragon’s Blood stonecrop, which displays sedum’s typical pagoda-like arrangement of leaves. The burgundy color changes into a greener version in humid areas, such as in Barry and Bonnie Altman’s Ontario lakeside garden. Winter weather deepens the red, but not as dark as Voodoo stonecrop (see Cecil Easterday’s regional-report photo below). Many sedums are evergreen but some (not all) need annual trimming back after blooming or in early spring to keep them low and remove spent growth (read Keith Yundt’s regional report).

Framing, filling, falling

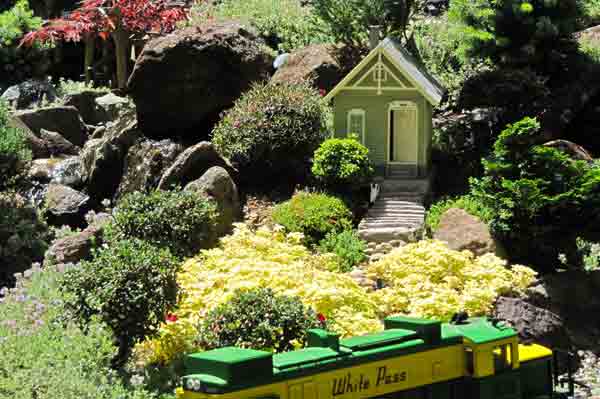

How do we love sedums? Let us count the ways. Xerophytes (plants that have adapted to dryland conditions) can crop out from between stones, as in photo 3, where Paul and Betty Levy planted orange Angelina stonecrop to contrast with gray boulders. Gary and Pam Everitt extended their moss rocks with tiny, mossy stonecrop suspended from craggy grooves in photo 4, just above a patch of gold moss stonecrop baking orange in the sun. Jerry and Alison Ogden love the contrast in photo 5; their golden Japanese stonecrop fills in a bright-yellow meadow in the middle of greens to highlight a cozy cottage.

Dave Gross plants sedums en masse to frame something special in photo 6; the welcoming green mat enhances the sign. Danny Saporito uses clump forming, non-invasive sedums to fill spaces between structures in photo 7; weeds won’t infiltrate the dense purple foliage. Roger and Jeane Samuelson grow spreading sedums between mountain-forming boulders in photo 8; draping stems burst into hillside bushes to soften the hardscape. In front of a mission, Bill and Juanita Eldridge fill scale pots tended by little friars in photo 9; sedums don’t easily dry out in the limited soil, and the scale-sized leaves are realistic enough to pull it off.

Weed’ em and reap

Nancy Norris

Any plant that grows vigorously must be controlled. The part we love is the ease of removing unwanted plants and the joy in giving them away without their drying between gardens. So, when blown-in seedlings prevent the turntable from turning (photo 10), Gary and Jonette Lee scrape away plants with a trowel or hand-held hoe. Larger plants and spent flower tops can be grabbed and yanked, removing a minimum of soil or ballast with them. Partial shade will slow down your sedums, as will underwatering. Over-fertilizing and overwatering will kill them. Think of your stonecrop plants as water reservoirs.

So many sedums. . .check out more: www.finegardening.com/plants/articles/creeping-sedums.aspx What about a sedum lawn, green roof, rock-wall cover? Would you like the tiniest one? It’s miniature stonecrop, Sedum requienii.

How to research a plant using a botanical name

When researching a particular botanical genus, like sedum, note that the first name is always the genus, which means “group.” Species, meaning “kind,” follows the genus. In photo 1 the yellow-flowered Russian stonecrop on the left is Sedum kamtschaticum. Once we’ve identified the genus, we can abbreviate it to S. kamtschaticum.

Sometimes plants have a third name, the variety, which is similar to the species. If it is a cultivated variety (cultivar), that part of the name is capitalized in single quotes. The red-leafed stonecrop next to S. kamtschaticum can be shortened to S. r. ‘Chocolate Ball’ (You may abbreviate the species if you’ve already referred to another Sedum rupestre).

You can start your online research at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sedum and click on a list of about 200 sedums, most with photos. Next, you can copy and paste the name of the plant you like into Google Images to see dozens of that plant on many online sites, including nurseries for purchasing plants.

Regional gardening reports

Zones listed are USDA Hardiness Zones

Question: What do you like/dislike about the genus (botanical group) of sedums, commonly known as stonecrop?

Keith Yundt

British Columbia, Canada

Zone 6b

Getting to know these babies

When I was first introduced to sedums, I didn’t know what to think of them—much like seeing a newborn baby for the first time: they are kind of weird looking and I was uncertain how to take care of them. I most often saw these odd little plants in small clumps in rock gardens. Little did I know that, just like a newborn baby, I would learn to love them and discover that they blossom into something beautiful.

In my railway I have three main types of sedum. The silver/gray-colored plant is Sedum spathulifolium ‘Cape Blanco’. It’s a plant native here on Vancouver Island and is used by the First Nations to make poultices; apparently the leaves are even chewed to ease childbirth. I find this plant is the most fragile of my sedums and the little stems are easily broken if walked on.

The green/red coral-colored plant is S. oreganum. Oregon stonecrop grows the fastest of my varieties, takes foot traffic, and consequently takes over pretty much anywhere it can find space. One thing I’ve noticed is that it will stop other plants, particularly thyme, dead in their tracks if they are planted next to it, so I relentlessly weed it out. To avoid seedlings, I aggressively pull out the spent white flowers—you can grab handfuls and pull them out and you are left with nice, fresh growth below—it’s very cathartic.

The yellow-flowering green plant in the picture is S. hybridum. Hybrid stonecrop seems quite “inert” in that it isn’t aggressive. It stands a little taller than the Oregon stonecrop, which adds a little more visual interest, and I love the bright-yellow flowers.

Cecil Easterday

Near Columbus, Ohio, Zone 5

Exterior decorator

We use a lot of the sedum varieties in the Sparta & Shelby Railroad. The deer won’t touch them, most of them are evergreen (often turning a deeper color for winter), and, contrary to the books, sedums thrive in our clay soil and are very cold hardy. They prefer sun but, when planted in part shade, the foliage remains vibrant but the bloom is sparse.

Frank Lucas

Pleasant Hill, California, Zone 9

Super sedum

I was so impatient to get trains running on our embankment railway that I didn’t bother to redo the existing sprinkler system. As a result, there are areas that get little moisture and one of these was smack-dab in the middle of the resulting railroad. What to do? Ah-ha! Sedum dasyphyllum to the rescue! Just as the book says, these guys will perform all year long with little care. Since Donna planted these, we have migrated offshoots into many other areas of our garden railroad.