Pruning is a learned practice. No one starts out knowing how to best prune a woody shrub. All of us just have to take a stab at it and learn as we go. We make mistakes, try to forgive ourselves, then find that plants will forgive us and grow back as healthy as before. We see that cutting only the tips of the branches (pinching back, as in topiary) causes too many buds to sprout below the cuts, resulting in even more branches that require removal later in the season. So, we plug away at our craft to improve it and to keep plants in scale and in health — a good “practice” (photo 1).

Empathic pruning

Every year I teach pruning at clinics during the National Garden Railway Convention. I line up shrubs, pruners, and gloves, and give a demonstration, then try to get volunteers to pick up the pruners and have a go at it. I’ve discovered that many a railroad gardener fears pruning because of “hurting” the limbs or life of the beings we call plants. According to scientific and experiential findings, both modern and primitive societies consider plants able to feel in some way.

I’ve done my own scientific research while a student at the University of Maine. I did get a “statistical difference” on multiple tests to prove that plants (or elements helping plants) respond to a human’s telepathic suggestions. Beyond physiology, I’ve also experienced 45 years of growing plants, including two decades of pruning shrubs to keep them small, tidy, and healthy. It takes effort and interest. When I’m finished pruning a plant, I’ve done my best to slow down growth so it can be admired in the garden. Does the plant “hurt”? Do my knees hurt? Maybe a little, but it’s a process of developing intuition about what’s happening with the plants (photo 2).

Directional pruning

Using topiary-style pruning, the plant will eventually have to be replaced, as it gets bigger and bigger each year, or will die when you cut into the center where no viable buds live. Directional pruning is similar to bonsai, the Japanese art of growing a (literally translated) “tree in a pot,” where families keep one plant small and alive for generations, even centuries. Each pruning cut is a choice: this branch or that branch, keep or cut, strong branch or weak one? Most decisions come down to a question of which direction you want the branch tip to be headed.

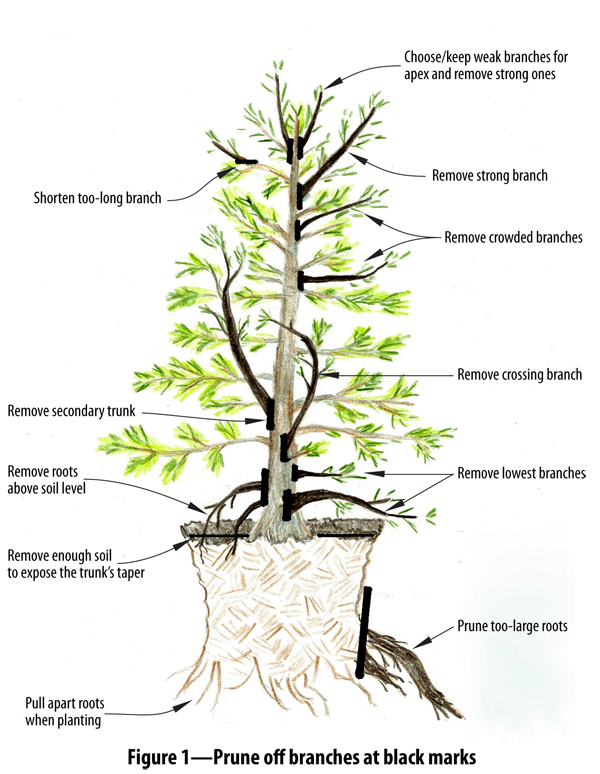

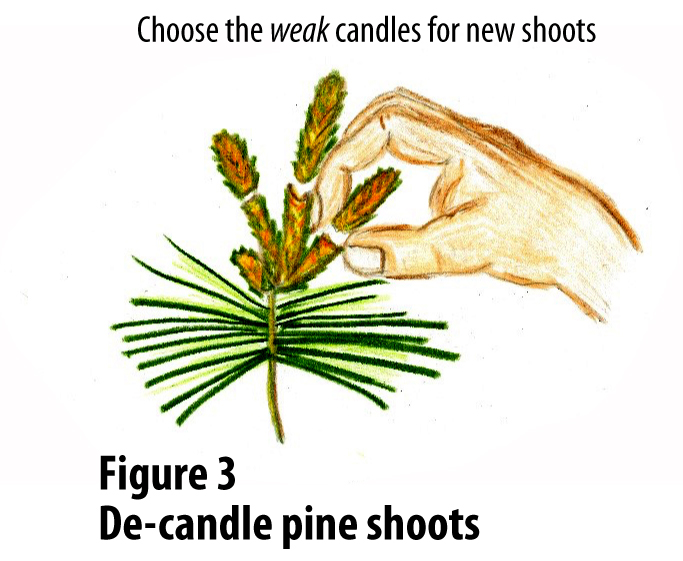

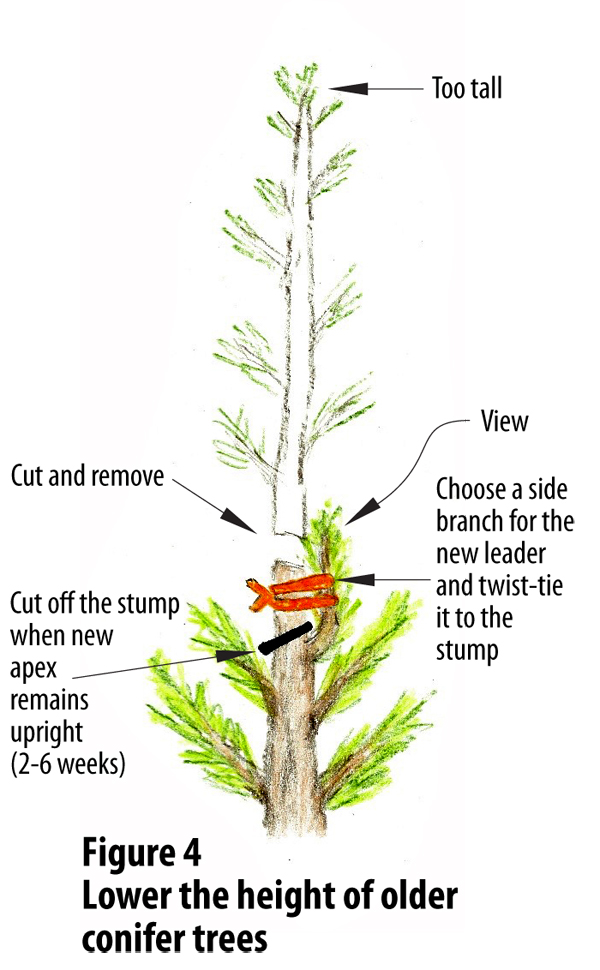

Even after years of pruning, most dwarf-conifer branches show their true colors — strong verticality and aiming for the sun. It sends young branches skyrocketing (photo 3) or sneaking up inside the shrub to create another trunk. As stewards, we can choose to keep the weaker branches (photo 4) and the horizontal or down-turning branchlets. We eliminate material, especially strong branches that detract from the shape we seek. This process helps the tree to grow more slowly.

To keep and shorten candelabra-type branches, cut them off at the elbow. Lift up or bend back each candelabra-forming branch, find a little branchlet underneath, and cut the branch at the point that will allow the little branchlet to remain as the new tip, with no stump. By angling the pruners horizontally, not vertically, no other branches will accidentally get cut. See figure 2 for this concept.

Most gardeners like Japanese steel pruning scissors (photo 4) because of their leverage ratio —large handles combined with small steel blades that resist sap adhesion. Their thin blades flatten out against the trunk to leave behind as little stem as possible. Stumps are ugly and sometimes sprout new branches. Gardeners with arthritis or other hand issues will like the ease of using ergonomically shaped or ratcheted pruners.

Time to practice

People like Amadeus Mozart, Kobe Bryant, and Pablo Picasso all spent at least 10 years of practice to become successful. They practiced with purpose, learning by doing, as well as learning from others. Because we all have different learning styles, I’ve illustrated some of the most basic pruning cuts needed for our small bonsai-like conifer trees in figures 1-4.

Practice and reap the rewards. For example, once you’ve got the hang of aesthetic pruning, you’ll be able to prune the full-size trees in your yard. Also, you’ll be able to take a less expensive, non-dwarf conifer or 1:1 tree seedling from your local forest and keep it small (photos 5 and 6).

Learn more

Join a local bonsai club. Get hands on, one-on-one instruction.

Read part two of this article: www.trains.com/grw/how-to/gardening/pruning-practices-part-2/

Watch videos online. See a pruning demo in this video: www.trains.com/mrr/videos-photos/videos/series/rehab-my-railroad/rehab-my-railroad-outdoors-episode-2/

Follow instructions in Nancy Norris’ book, Miniature Garden Guidebook, chapter 8, “Pruning trees for a scale appearance” [out of print — Ed]

Regional gardening reports

What’s your pruning story?

Todd Brody

Santa Ana, California, Zone 10

The graying of the garden

It was our pleasure to be hosts for the 2012 West Coast Regional Meet, where Nancy Norris came to see the garden as she gave us some help about pruning. I took her advice and cleaned out all of the dead stuff from “inside” the little chamaecyparis trees and was rewarded with a nice little blue-green “tuft” at each bare node. I see that, in addition to not letting the light through, the dead stuff holds the moisture against the bark, which leads to rot in those areas. I think that these will come back nicely now. [Dark moisture also invites slugs and snails to nibble on bark. If they girdle a branch it will die; if it’s the trunk, the whole tree will die. — NN]

Bob Evans

Lafayette, California, Zone 9

200 scale-feet tall

When I started building my railroad in 1994, I had always envisioned a mountainous region with a forest. I had to jackhammer part of a concrete slab in the area where I wanted to build and I used the rubble for the mountain, covering it with topsoil. I consulted Sharon Yankee at MiniForests by Sky about the best trees, and I bought my first 12 trees from her: six dwarf Alberta spruces and six Eric’s white cedars. They were about 6-8″ tall when I planted them. I used drip irrigation and located them in a sunny spot, so they grew pretty well. I didn’t prune them for five years.

Then I went to a pruning clinic by Don Herzog of Miniature Plant Kingdom [out of business — Ed.] at a BAGRS annual meeting. For the hands-on clinic, I brought an Eric in a gallon can. Don taught me the basics of pruning, especially not to be afraid to be aggressive, and how to clear space between major branches. I remember leaving for the convention in the morning with a bush and coming home with an almost denuded stem. My wife and son were shocked at the difference.

Armed with my new-found knowledge, I attacked my 3′-tall Erics. Since I hadn’t pruned them, the branches had gotten spindly, as the tips were reaching out for more light. I used Don’s techniques. Since then, I have pruned the trees once a year but don’t top them. Using the 10′ rule, I think they look good. Besides, in my vision for the railroad, the trees are not a regular forest, but a destination — a “Big Trees” nature area that justifies a quaint, German-style tourist hotel and hiking area with scenes of backpackers, campers, and wildlife.