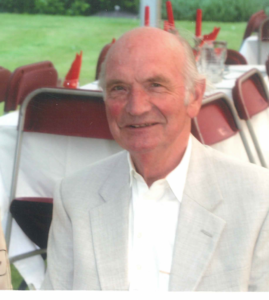

Editor’s note: This article was submitted to Garden Railways in 2015. In contacting the author recently to inquire about publication, we learned that he passed away in 2023. We offer our condolences to the family and are honored to present this article in his memory.

See the author’s original railway story in the August 2001 Garden Railways.

The hobby of garden railways has been described as one that can embrace a wide range of aims and emphasis. For some railways, what matters most is the fine-scale modeling of the locomotives and their performance. For others it is the “civil engineering” that takes priority, with spectacular bridges and picturesque viaducts. Then there are the garden railways that are conceived and created as a three-dimensional art form, an “adventure in imagination.” The building of the Gwensyn Valley Railway was approached more as an art than a science.

Garden railway landscapes

A garden railway can be compared to a landscape painting, containing a background, middle ground, and foreground. A hazy outline of distant hills might be seen on the skyline. In the middle distance there could be features such as a windmill, village church, or ancient ruin. In the foreground would be carefully depicted figures, a shepherd with his flock, farm animals, and village folk.

A garden railway may also be thought of as being made up of background, middle ground, and foreground. Where the track is closest to the observer, the track itself and all lineside buildings need to be carefully modeled and to scale. From whatever distance the GVR is viewed, the aim has been to portray a credible railway line.

Obtrusive backgrounds

Even when the garden railway is sited some distance from the house, there are still likely a few obtrusive structures in sight. These might include a garage, garden shed, a long brick wall, or ugly metal fence.

With regard to the GVR’s backgrounds, we were fortunate in already having tall mature trees around three sides of the chosen site. The fourth side was originally open to the driveway. Such an open view would be unwelcome, but I solved the problem by building a six-foot-high rustic fence. I planted bushes and creepers planted to soften the hard, straight line of the fence tops.

Avoiding tracks on sticks

The upper lawn area was the only level piece of ground in the two acres of our gardens and orchards. It measured around 2,500 square feet and seemed the most suitable site on which to build a railway. The idea of such a labyrinth of lines crisscrossing the lawn was a non-starter. My wife Liz, in her role as head gardener, wished the lawn to remain, well, a lawn.

The lawn wasn’t a true right-angled rectangle, but a more interesting quadrangle shape. Only one side had been bordered by a flowerbed. The other three sides were next to the original steep grass banks, behind which were high hedges. This meant that there would be plenty of space left for the railway line to encompass the lawn without encroaching upon it. So we built a 150-foot-long walkway using 2-foot-square paving slabs to run around three sides of the lawn. This enabled the new pathway to act as a boundary line separating the different worlds.

A different challenge was the proposed site for the lowest part of the line, which would run behind the tall hedge alongside and above another new pathway three stone steps down from the main lawn. Ground level there was about 3 feet lower than the lawn. This was below where the main station with engine sheds and workshops would be built. The railway area and village would need to be within easy reach. We had to find a way of raising the line there to a convenient waist height level.

We decided to build a permanent 2½-foot-high retaining wall of natural limestone, backfilled with broken bricks and earth tamped down to form a solid base for the track. It was well worth all the work involved.

The graveyard effect

The natural habitat for narrow-gauge railways in Wales is rock terrain. But beware. To reproduce rock features in miniature is an art. One such pitfall which the GVR managed to avoid could be called the “graveyard effect.” All kinds of gravestones can be found in many English and Welsh village church yards. Some are ancient, shattered, and moss-covered, toppling over at crazy angles. Others are modern, arranged in straight lines, and made up of many different types of stone. In the same way, if disparate types of rock are placed haphazardly alongside a garden railway, they can never resemble any natural rock formation.

Limestone and sandstone rocks are more suited to rockscaping in miniature than granites because they are sedimentary in origin. This means they are made up of layers of sediment laid horizontally on an ocean bed. With millions of years of compaction and earth movements, they can become tilted, yet still retain the same alignment along clearly distinguishable bedding planes of stratified rocks.

It is these natural rock formations which the Gwensyn Valley Railway has sought to reproduce in miniature. As a former geologist, I felt this particular pursuit of realism was all important. For other hobbyists, an understanding of the underlying geology can be invaluable and the results rewarding.

Looking like just another short line

The Gwensyn Valley Railway is a relatively long one by British garden railway standards. The distance is almost 300 feet. If the stations are positioned too close together, then the line would seem shorter. So all the stations on the GVR have been sited so that no station can be seen from any other. If a visitor is seated on the Great Western Railway platform bench beside the intermediate station of Abergwesyn, the two other mainline stations of Garth Wells and Pen-y-Cerrig cannot be seen. One is well hidden behind a high hedge and the other is screened by bushes fronting a rustic fence. Had the stations not been concealed from one another, then the desired illusion of a much longer, and more realistic, railway would have been lost.

Lacking a sense of proportion

A carefully modeled railway in miniature surely merits an equally miniature landscape setting. In the case of the GVR, this meant a scale of 1:20 or thereabouts.

When seeking suitable scale lineside plants, beware of specimens labelled “dwarf.” Coniferous trees such as dwarf Alberta spruce (Picea glauca ‘Conica’) will start with delightful green foliage and look entirely in keeping with the scale of the railway. They do need to be kept in check with regular pruning. If neglected, their girth can get too great and the inner branches die off.

Dwarf versions of flowers such as tulips or daffodils are actually about half size of their full-size counterparts and look out of place as intrusive giants. Instead of so-called dwarfs, look for truly diminutive varieties. Many mints and thymes come into this category and act as good ground covers. Dark green leaves seem to look more natural than light greens and those with variegated leaves look cultivated rather than wild.

Welsh landscapes include large areas of heath and wild moorland often covered with bracken, a coarse type of fern. A versatile plant which simulates bracken and spreads easily as a low ground cover is cotula (Cotula sp.). Another useful mountain plant in miniature is creeping broom (Genista pilosa var. minor). This is a tiny variety of wild broom, with bright yellow flowers appearing in the early summer months.

Roads to nowhere and passengers in a hurry

We often read that our garden railways should have something to do and somewhere to go. But what about those little roads modeled alongside the stations? Surely they, too, should be going somewhere. Fortunately such roads to nowhere can easily be diverted to give the appearance of actually going somewhere. Often a gap in a hedge can be found or made so that a road may be re-routed into it. Road vehicles can be positioned giving the impression of heading into a wooded area on the way to the next village.

Even tiny details can make a difference. Like, for instance, locomotives with or without a driver (and fireman maybe) in the cab. When choosing suitable railway passengers, none of them need to appear to be dashing to catch their train. The local country folk and summer visitors on the Welsh narrow-gauge railway are more likely to stroll up to the little carriages at a leisurely pace, lingering and chatting before boarding.

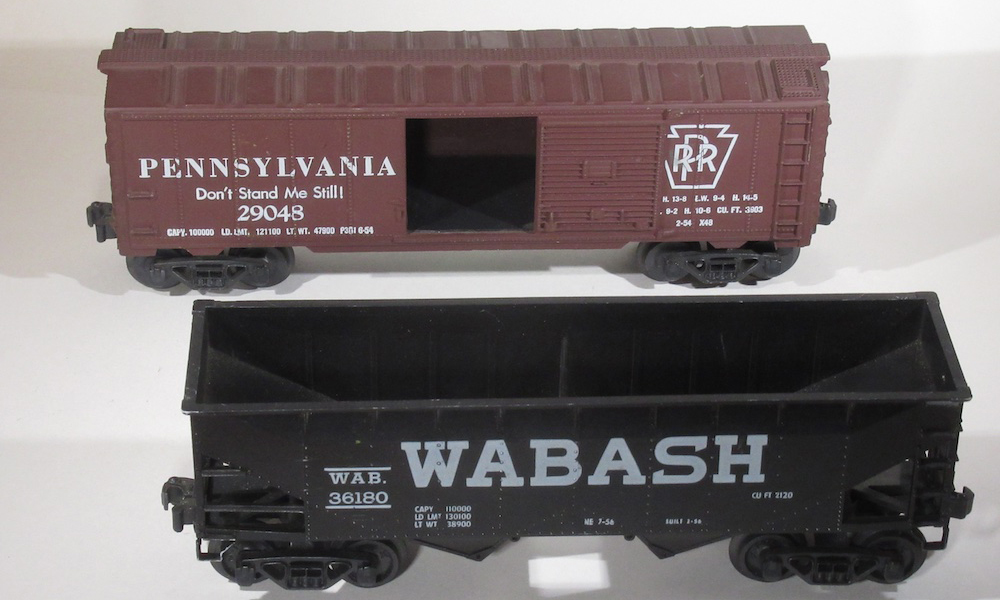

Whether to weather?

For the GVR, the weathering of the wagons in limestone quarry was easy. They have been left outdoors and weather naturally, suitably work-stained and rusting. But what about the locomotives? Most didn’t need to be weathered because they would still be in keeping with their prototypes of present day Welsh narrow gauge railways. A number of these lines have imported locomotives from continental Europe, Africa, and the Americas. The new arrivals become the most photographed star attractions, lovingly restored, freshly painted, and regularly cleaned. This allows narrow gauge garden railways to run brand-new engines without any need for weathering.

The one exception was Hank. Hank is an ex-Lionel 0-6-0 tank engine bought by chance when visiting Cambria, a small town in California. I found a shop owned by Samuel Munsey, a founder member of the A.W.N.U.T.S society. (Always Whimsical and Not Usually To Scale). I contributed a number of articles to the society’s magazine during its short life. Hank, on sale at the bargain price of 90 dollars, was an offer not to be refused. It was weathered by Sam and looks right on the GVR’s California-style backwoods branch line leading to Old Bryn Tunnel.

The never finishing touches

Model railways are often complete but never “finished.” How true. The GVR had been a complete line more than 20 years ago, but new features are still added. One recent project was the modeling of a prehistoric burial chamber, a simple structure made from flat, weathered stones. Ancient monuments like this are called cromlechs in Wales. Its location is a favorite destination and viewpoint during the tourist season.

About the author

After serving with the Royal Signals in WWII, the late Bryan Betts studied geology at the University of Bristol. He was a member of the Danish expedition to North East Greenland in 1951. His main career was as International Director at a London advertising agency. His interests included languages and writing. He published a semi-autobiographical novel in his 80s.

The railway at a glance

Name: Gwensyn Valley Railway

Size of the railroad: 80’ x 100’

Scale: 1:20.3 (or thereabouts)

Gauge: 45mm

Era: The present

Theme: A 3-foot narrow-gauge line in Wales carrying timber and limestone. Passenger traffic from Easter to October for visiting tourist attractions.

Age: 25 years

Motive Power: Battery

Length of line: About 300 feet

Maximum gradient: 2½%

Type of track: LGB (flex), Ten mille, and Peco

Minimum radius: 4 feet (main)

Structures: “Gravura” buildings by Peter Jones, solid resin models from Cain Howley, kit built and scratchbuilt

Control system: Manual and radio control

Plants on the Gwensyn Valley Railway, Herefordshire, England

CONIFERS

Atlantic white cedar

Chamaecyparis thyoides ‘Andelyensis’

Dwarf Alberta spruce

Picea glauca ‘Conica’

SHRUBS

Dwarf rhododendron

Rhododendron ‘Cadicuns’

Rhododendron ‘Artic Bleu’

GROUND COVERS

Creeping cotula

Cotula sp.

Creeping broom

Genista pilosa var. minor

Saxifrage

Saxifraga ‘Saxony red’

Various thymes and mints

Corsican mint

Mentha requienii

Thyme red carpet

Thymus coccineus

White moss thyme

Thymus praecox ‘Albiflorus’