What is an operating session?

Operating sessions attempt to mimic the activities we see on a full-size railroad.

To support a successful operating session, a garden railroad must have certain characteristics. There must be multiple industries where cars can be spotted. The more unique industry locations on the railroad, the better. These car spots must be easily accessible by train crews for coupling and uncoupling. After the cars are spotted and the train moves on to the next location, the cars must not block the main line or prevent another train from passing.

While you can hold an operating session with a single locomotive/train, having more than one locomotive running at the same time makes for a more interesting operating session. If these multiple locomotives are forced to share sections of track, it makes the operating session more challenging.

Sharing track can be managed through self-dispatching. With self-dispatching, each train crew must be aware of what the other train crews are doing to avoid conflicts over shared track. With a central dispatcher, each train crew need worry only about their own activities, but they are required to keep the central dispatcher advised of their activities and must obtain permission from the dispatcher before using shared track.

Local trains may run between towns A and B, stopping at various industries located along the way to pick up and to leave cars. When a train arrives at either A or B, the locomotive may need to reverse direction for the return trip. This requires a turntable, a wye, or a reverse loop. Additionally, the cars in the just-arrived train have to be separated, sorted, and assigned to new trains, a task for the yardmaster and the yard switching crew.

What is commonly called a point-to-point railroad fits this scenario the best. However, point-to-point railroads don’t work well for exhibiting the railroad to visitors or for casual railroading, because of the need for interaction at each end to turn the train around for the return trip. Point-to-point and loop-to-loop designs require the use of shared track between the two ends.

A loop railroad is ideal for use as a display railroad, as it needs little to no interaction when running a single train. A train on the loop can just keep running. If a second train is added going in the same direction, if the speeds aren’t perfectly matched, they will require some supervision to ensure one doesn’t catch up with the other.

Two types of operating sessions

There are multiple ways of implementing an operating session. Some prefer a session that closely mirrors what happens on full-size railroads. Others lean toward whatever will make the session simple and fun. Many of the steps and procedures implemented on railroads are there for one of two reasons — to increase safety or to make money. Our garden railroads aren’t designed to make money, and due to the small scale of our locomotives and rolling stock, safety procedures aren’t as crucial.

The following description of an operating session is based on the system used by our club, the Rose City Garden Railway Society. It is by no means the only way to operate.

In full-size railroading, there are basically two types of trains. The first is the local train, which progresses from location to location at a slower pace because it makes many stops along the way. The second type is the through or express train, which typically travels at high speed from origin to destination, making few or no stops in between. The operating characteristics of these two train types vary so greatly that including both types in the same operating session can be tricky. But some garden railroad operators enjoy that kind of challenge.

Switching-based operating session

Let’s follow a local freight train as it leaves the yard at town A, headed for town B. Each train is assigned an engineer and a conductor/brakeman. The engineer will operate the locomotive, controlling direction of travel and speed. The conductor/brakeman is responsible for determining what moves will be made, setting switches in support of those moves, and operating the appropriate uncoupling device when needed. The conductor must also obtain clearance for any use of shared track, either by coordination with other train crews (self-dispatching) or by communication with the central dispatcher.

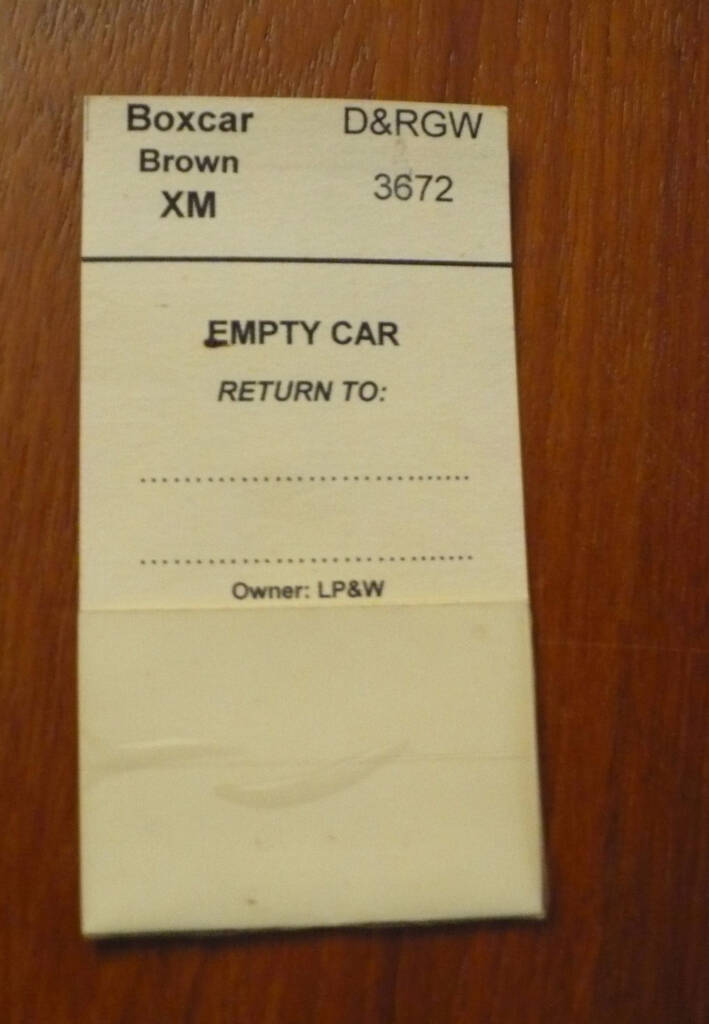

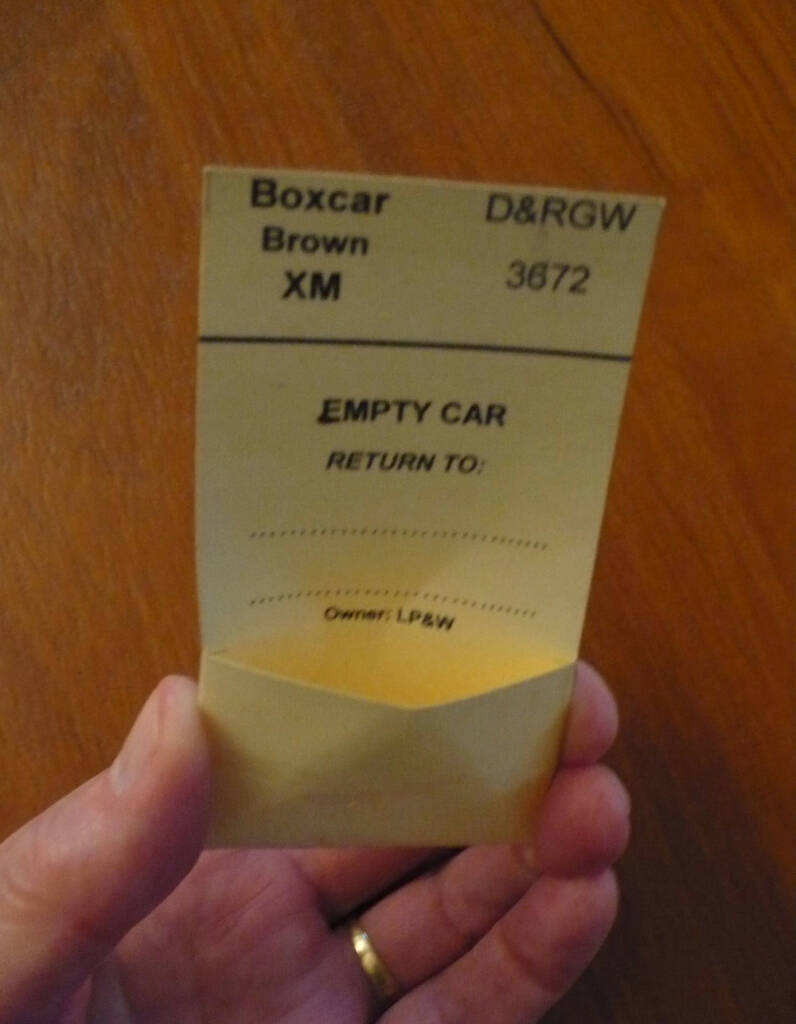

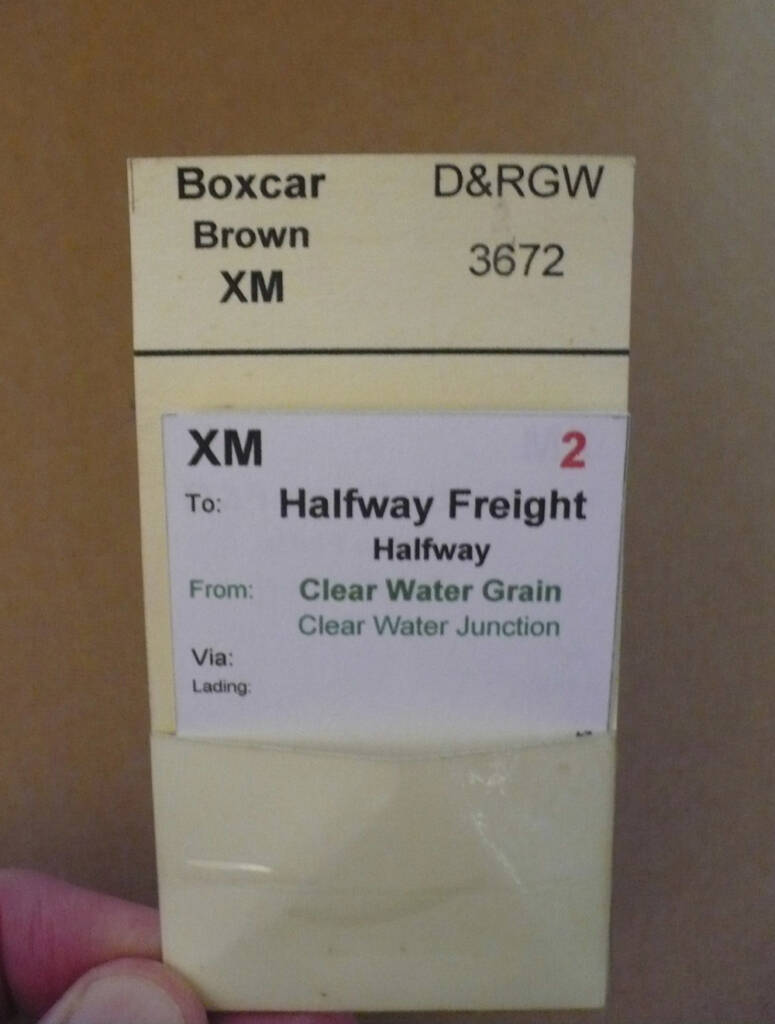

Each car in the train has an associated car card (see photo 1). The car card contains information about the car such as its type (boxcar, gondola, etc.), its basic color, the name of the railroad that owns the car, and most important of all, the unique identifying number on the car. As the train leaves the yard, the conductor should have one car card for each car in the train. This card will remain with the conductor as long as the corresponding car remains in the train.

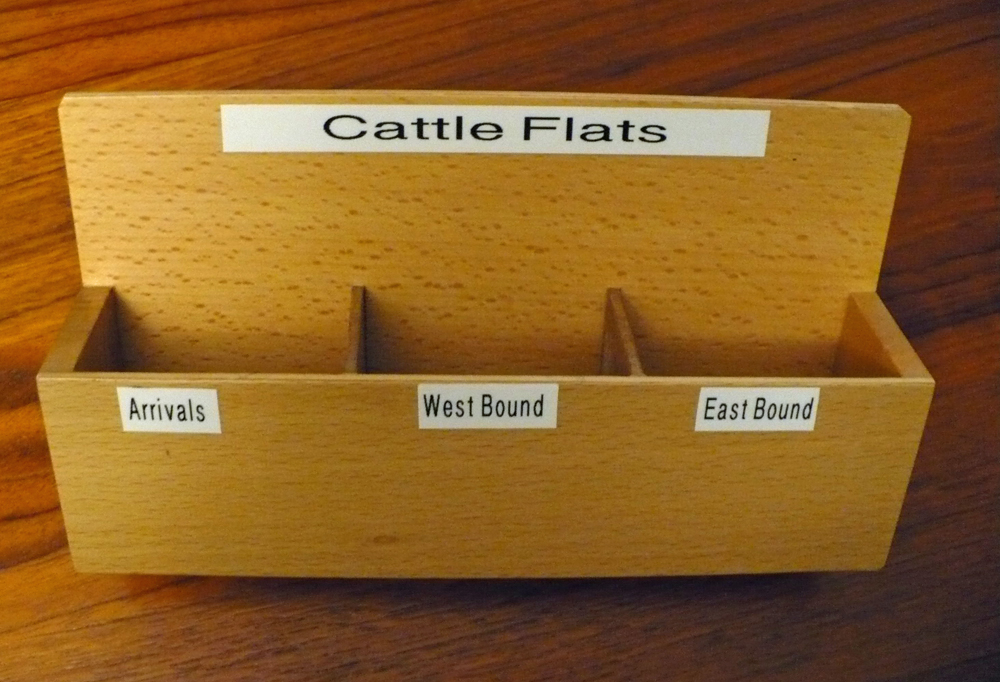

When the car is delivered to an industry, the corresponding card will be left in the arrival box (see photo 2) located at or near the industry. Note: Some railroads will have multiple industries at one location, and all of the industries at that location are likely to share the same arrival box. The different slots in this box may correspond to different industries at the location, or different car spots at the same industry.

Each car card contains a pocket into which a waybill can be inserted (see photo 3). While the car card describes the car, the waybill describes the routing and destination for the car. The waybill specifies the type of car, which should match the car type listed on the car card. The waybill also includes the location the car is coming from and the industry to which the car needs to be delivered.

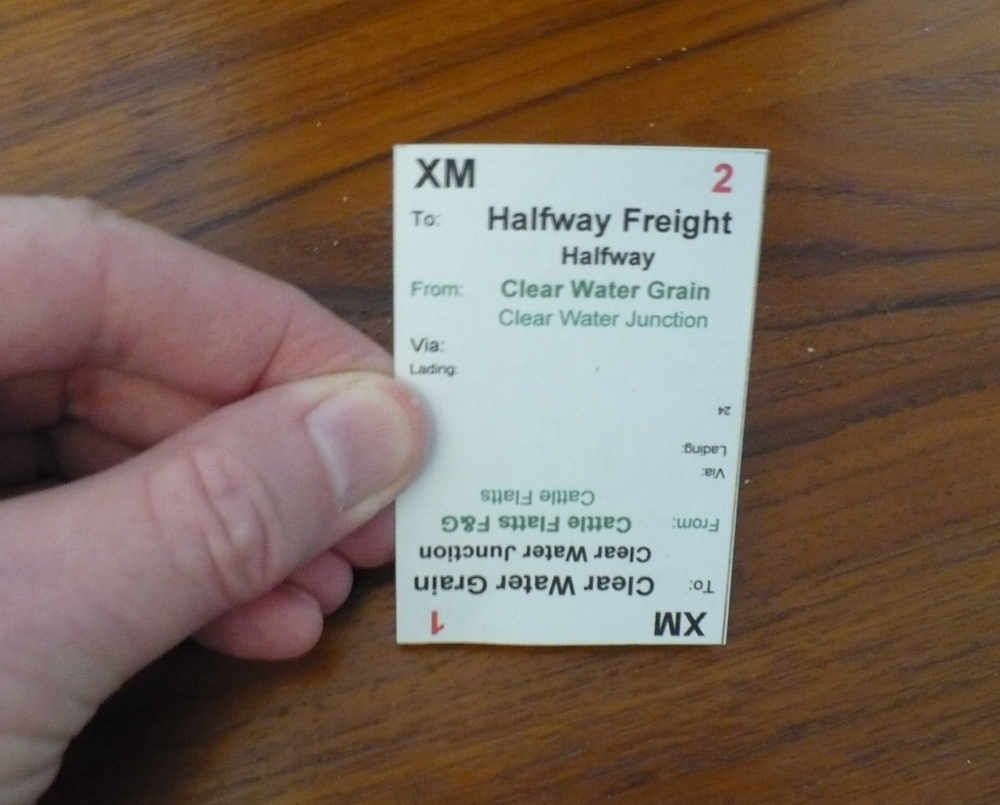

For the purposes of our operating session, we use a two-sided, four-position card as a waybill (see photo 4). Each waybill card has two waybills on the front (top and bottom) and two more on the back (top and bottom). In the corner of each waybill is a number that uniquely identifies the four waybills. These waybills are designed to be used in order, first 1, then 2, 3, and finally 4, before cycling back to 1. It is called a four-cycle waybill.

For the purposes of our operating session, we use a two-sided, four-position card as a waybill (see photo 4). Each waybill card has two waybills on the front (top and bottom) and two more on the back (top and bottom). In the corner of each waybill is a number that uniquely identifies the four waybills. These waybills are designed to be used in order, first 1, then 2, 3, and finally 4, before cycling back to 1. It is called a four-cycle waybill.

When the waybill card is inserted into the pocket on the car card, only one of the four waybills is visible. This is the active waybill (see photo 5). The operating session host will use the waybill number to determine which of the four waybills should be used next after the car has been delivered to the destination on the current, active waybill. Cycling (advancing the waybill to the next position) is handled by the host after the conductor places the car card for the delivered car into the arrival box.

Each railroad may have house rules. For example, due to siding length limitations, there may be a maximum length set for trains moving on the main line. (See below for an example of rules on one railroad).

Prior to each movement, the conductor should review the waybills associated with their train to determine the most efficient way to deliver the cars to the destinations. Some switching problems can be quite complex, so it is best to have a plan before you start switching to minimize the number of moves required.

At each industry, after completing any required deliveries but before departing for the next industry location, you should add to your train any cars at that location that are waiting to be moved to a destination in the direction your train is traveling. This requirement applies to every location your train passes through, even if you didn’t deliver any cars there. If more than one car is waiting to be moved, you are required to take them in the order in which their car cards appear in the outbound box.

The requirement to pick up waiting cars is waived as soon as your train reaches it maximum authorized length. You may not “cherry pick” the cars that are the easiest to get to. Cars must be picked up in the order that the car cards appear in the outbound box. The only exception to this is if the local rules for train length are based on physical length. If your train is 1 foot under the maximum length, you pick up the first car in the outbound box that is 1 foot in length or less. If the first car in the outbound box is 15 inches long, you may skip over it to pick up the next car that is only 10 inches in length. There may be other local rules that allow a car to be skipped over in the outbound box.

Before departing for the next location, the conductor must establish that the main line is clear for the train to use. If the operating session is using a dispatcher, the conductor must contact the dispatcher to obtain clearance for the move to the next location. If no dispatcher is on duty, then some other means must be used to establish that it is safe for the train to move to the next location. This may require the conductor to communicate with the closest train in the direction in which his/her train wants to travel to coordinate with their movement requirements.

Deviations from real-world railroading

While an operating session has the goal of duplicating what happens on full-size railroads, there are some deviations. Running multiple trains at the same time on a railroad that might actually see only a few trains per week is a deviation. But we do it so that everyone gets a chance to work a train, because that is where the fun is for the hobbyist.

Another area of deviation involves tight schedules. We scale down distance and speed, but not time. In the real world, passenger trains cover long distances at high speed with only occasional stops. The time between stops is likely to be measured in hours rather than minutes. In garden railroads, stations are likely to be only a minute or two travel time apart.

When the operating session is of the just-run-trains variety, one of the goals is to have lots of unscheduled, random meets between opposing trains, forcing one to go into a siding to allow the other to pass. This may also occur with trains going in the same direction if, for example, one train is a high-speed passenger train and the other is a slow logging train. The logging train will be required to pull into a siding to allow the faster train to pass. In the real world, you aren’t likely to find this combination, but again, the fun aspect of the operating session comes into play.

Pre- and post-operating session work

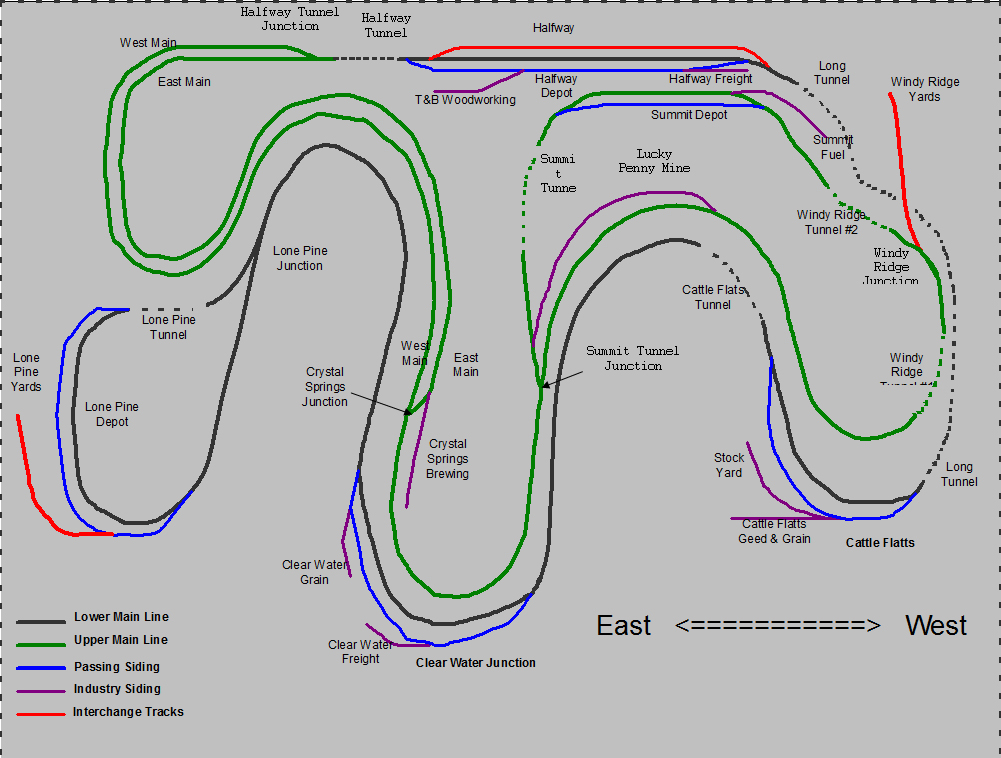

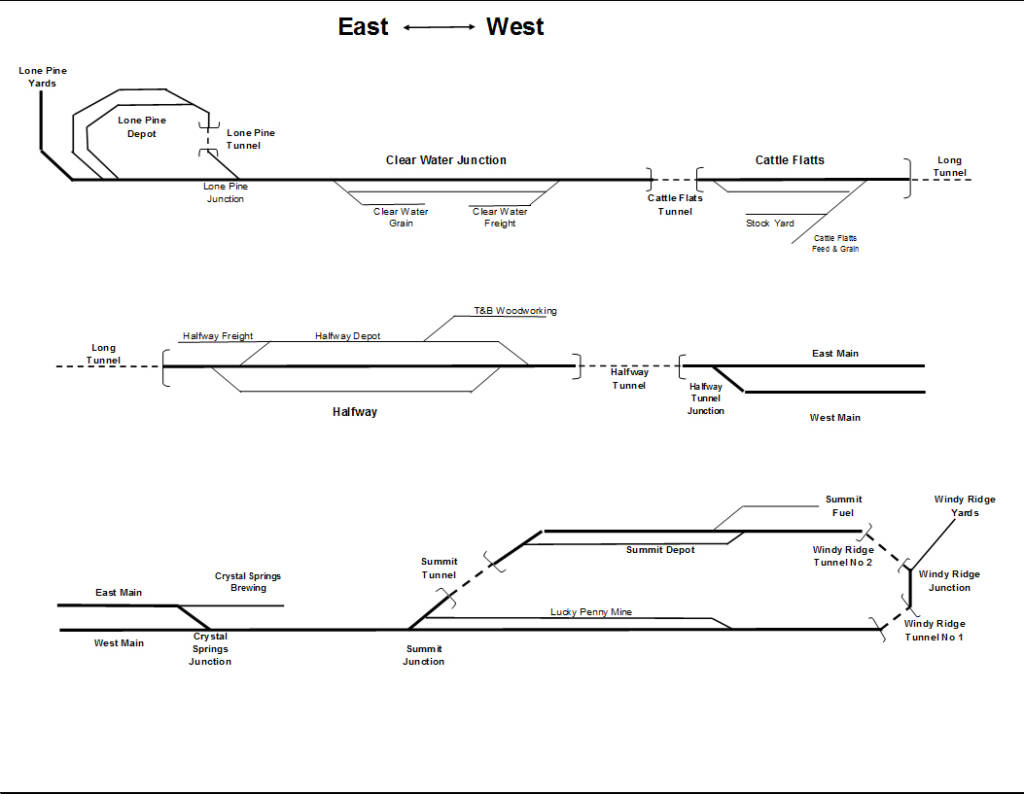

Some amount of pre-session work must occur before a successful operating session. The host will be familiar with the railroad, but guest operators aren’t as likely to be so familiar with it. So it falls to the host to provide maps to each crew, both topographical (see photo 6) and schematic (see photo 7), showing where each town, industry, or landmark is located. Having the dispatcher issue an order authorizing a movement that involves a meet with another train at siding XYZ won’t work well if the crew isn’t familiar with the location of XYZ. Railroad signage also helps participants to match physical locations to that same location on both the topographical map and the schematic map.

While in theory, any car could be sent to any location, it will look and feel better if the movements for this car make sense. Moving a flatcar to a mine tipple to load ore may provide a switching challenge for the crew, but that choice of car doesn’t make sense. With four-cycle waybills, the host must carefully choreograph the movement of the associated car to four distinct location and then back to the first location.

Even if multiple sessions all start with the same initial placement of locomotives and rolling stock, using the same waybills, the use of the four-cycle waybills combined with the variation in speed and skill level of the various train crews will lead to a different result for each session. There may be trends that need to be addressed before the next operating session to improve the session.

Some of the trends to watch out for are:

- Too many cars being delivered to the same industry at the same time, resulting in more cars than the siding can hold

- Not enough cars being delivered to an industry, leaving its siding empty most of the time

- One or more cars not getting moved because every train coming through is at capacity

- Congestion at one industry location, with too many trains either switching or waiting to switch one particular location

Employing a central dispatcher

The implementation of a central dispatcher varies from railroad to railroad. If the railroad is reasonably complex, the central dispatcher may need a large map on which he/she can place some form of token for each train indicating the presence and direction of the train on the map.

Dispatcher communication will also vary. On some railroads communication will be via a dedicated phone system connecting each switching location with the central dispatcher. This may be either a wired or cordless phone system. Some may choose to implement dispatcher communication via small, hand held radios, while others may use the “tennis shoe” method (lots of running back and forth to talk to the dispatcher).

Electronic communication generally involves a shared line where everyone can hear what everyone else is saying. When contacting the dispatcher, conductors should always identify themselves by their train ID, usually the engine name/number, their direction of travel and their location (i.e. D&RG No. 5 – East Bound – at Cattle Flatts), followed by their status update and/or request. The dispatcher should repeat the conductor’s message to ensure that it was clearly received. When the dispatcher issues an order, the conductor should repeat it to ensure that it was correctly received (i.e. D&RG No. 5 – East Bound – You are cleared from Cattle Flatts to Clear Water Junction). One advantage of radio communication over phone communication is that everyone can hear and be aware of what everyone else is doing.

Operating session goals

The goal of an operating session is to increase the enjoyment that we derive from our garden railroads. If an operating session isn’t fun, then it needs to be changed to make it fun. Not everyone derives enjoyment from in an operating session, so don’t feel that you are missing something if you get no enjoyment from participating.

Learn more

Basics of waybills and car cards, part 1

Basics of waybills and car cards, part 2