When I started planning my first backyard railroad in the 1980s, naturally one of the first tasks was to pick out a name. I quickly hit upon “The Flint Hills & Permian Basin Railroad,” named after the geographic areas in Kansas and Texas, respectively, where my wife and I grew up. I thought it had a good ring to it and it provided the basis for some invented history of the railroad, which, in turn, gave a framework for choosing rolling stock, buildings, etc.

Some years later, I came across a description of the Kansas Central Railway, a narrow-gauge road that coincidentally ran from Leavenworth through the Flint Hills of Kansas, westward toward Denver. The route passed just 20 miles from my inlaws’ house, so I determined to find out as much as I could about it, which was not much at the time: one page in American Narrow Gauge Railroads. In 1999, a Nebraska historian published the first (and only) history of the railroad, Kansas Central Narrow Gauge, which had a lot of useful material, including historical documents, route maps and a precious few period photos. And in 2002 a small volume about Garrison, Kansas, the railroad town 20 miles away and now underwater since 1959, added a few photos. But honestly, information about the KC remained rather thin.

The Kansas Central was headed west from Leavenworth, on the Missouri River, to Denver to join up with the D&RG. They never made it. Like so many ambitious rail projects of the time (the early 1870s), they got 156 miles built before an economic depression hit. Expansion stalled and traffic was minimal, since the KC didn’t really go anywhere yet. The railroad was gobbled up by the Union Pacific in 1879 and the line was eventually standard-gauged in the early 1890s.

Because it was never finished to its original plan, the railroad never connected anything big; it ended in Miltonvale Kansas, one of many small, undistinguished towns along the line. After regauging, the KC was renamed the Leavenworth, Kansas & Western, and puttered along until another depression in the 1930s, combined with a growing network of paved rural roads and increasingly reliable motor vehicles, finally rendered it uneconomical. The line was closed and the rails were lifted in 1935.

A railroad doesn’t just sit lightly on top of the landscape; it digs into and changes the earth. Even on level ground, it leaves remnants of roadbed gravel or treelines that spring up along the right-of-way ditches. So I began wondering what remnants of the physical plant I might find. Since the railroad ran just a few miles from home, I decided to find whatever remained.

My first resource was Kansas Central Narrow Gauge by I.E. Quastler. He reproduced many period route maps, but these are only general indications of the path of the railroad. They did show the towns to search for, though. Quastler opined that all there was to see were some “crumbling remnants of the right-of-way.” But his photos of a limestone culvert and a tree-choked cutting through a hillside were enough to encourage me.

However, I was fortunate to have a tool unavailable to Quastler in 1999: Google Earth. Using its satellite photos, along with online USGS topographical maps and route maps in the books, I started at the known termini (Leavenworth and Miltonvale, KS) and at the former location of Garrison and began scouring Google Earth for apparent signs of a disappeared railroad. Although the Kansas Central has been gone for over 80 years, there were enough cuts and fills to quickly locate its route. Starting at Garrison, I went east and west, finding the places where the railroad had left permanent scars on the landscape.

I looked for color changes: bare rock showing on the side of a cut, a “stain” in a field where ballast kept wheat from sprouting, or just a different-colored line through a field. Often, a row of trees or bushes would be the most visible remnant, growing along a drainage ditch or fence line parallel to the roadbed.

I also used US Geological Survey (USGS) topographical maps, Sanborn fire maps, and other historic maps to trace the route with greater precision. According to Kansas Central Narrow Gauge, the KC was mocked for its cheap construction and track that weaved about like a drunken sailor. This weaving was the result of making the minimum number of cuts and fills. Not unlike many railroads of the era, the railbed tried to follow the contours of the land to maintain a flat grade, so it weaved around to avoid hills and creeks. This can be seen most clearly by comparing a route map with US Geological Survey maps to see how the railroad tried to follow the contour lines closely.

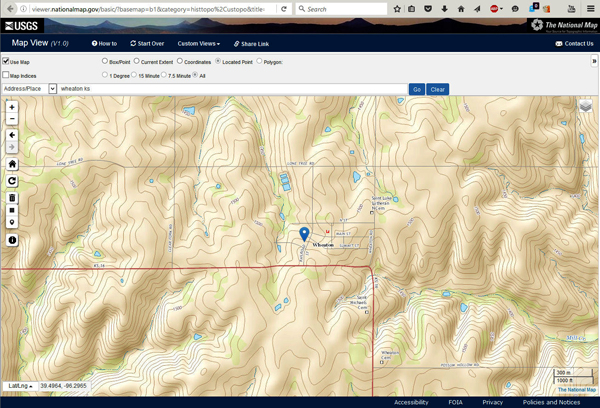

USGS maps are the official, highly accurate description of the land of the United States. They feature contour lines that follow an elevation across the landscape—every point on a contour is the same elevation as the rest of the line. Contours and shading make it easy to see where the earth rises and falls by even a few feet.

There are lots of companies on the web that want to sell you topo maps but we’ve already paid for them by helping fund the USGS. Go to their website, nationalmap.gov/basic, and search for the one you need. Downloads are free. (Photo 1)

Historic city maps, also found on the Internet, showed where the KC tracks went through various towns. Most of these little places had a Railroad St. to confirm the route. (Photo 2) When the line “disappeared” from the satellite photos between towns—usually when it crossed a field that had been cultivated intensively for the last 80 years—I consulted the USGS topographic maps to find the contour lines that would keep the track closest to level. I was not disappointed. After a couple weeks of practice, there were only a few miles of right-of-way that I couldn’t identify with high confidence.

Give it a try yourself. Photo 3 shows the route north out of Garrison, along what is now Dry Creek Road, on the left side of the screen, and Hwy 16, along the top of the screen. Can you spot the tree lines, berms and ditches that lined the northbound roadbed as it curves around to run east (photo 4)? When you’re driving along Hwy 16, you can clearly see the 150-year-old berm and the cuts through high spots where the track was laid (photo 5). This was my first positive confirmation in the field that my investigative work had paid off.

Before hitting the road, I prepared by taking lots of screen shots, marking the route in red, and loading them onto my phone. I then made a list of places that would be easy to see from the various roads of the area.

This was a learning process, training my eye to distinguish abandoned roadbed from creeks, ditches, stone outcropping and cattle paths. At one time, I thought my number one priority was a spot south of Arrington, where it appeared that the railroad crossed the Delaware river and there were still crossties on the ground! Further examination, however, revealed it to be a fence line whose shadows were exactly the size and orientation that ties would have had. Topo-map study revealed that the railroad actually crossed the Delaware many miles to the east. Lesson learned: see what you’re seeing, not what you hope to see!

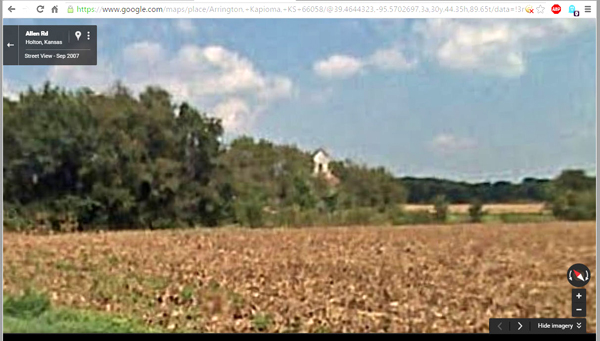

As I was getting into this project, Garden Railways (Apr. 2016) printed an article by a modeler who had found and built a model of a grain elevator that still stands on the former route of the Kansas Central. Bingo—I found it easily on Google Earth and had another fixed point to work east and west from. And as a bonus, Google Street View showed me that I had the right spot: you can see the top of the elevator peeking up above the trees just right of the center of photo 6.

Having several known points on the railroad, I began honing my terrain-spotting skills and zeroing in on places the ghost railway crossed or ran along current roads.

Then we began stalking the roadbed in the wild, sometimes along familiar roads, where we had never looked closely before; sometimes along one-lane dirt tracks, where we really should have had a farm truck.

On these excursions, we found more than just cuts and fills. In addition to the elevator at Larkinburg, there are various buildings that have survived in one condition or another. (Photos 7 and 8). Even after more than 80 years, there are still artifacts scattered along the route. We stopped where the route crossed a country road west of Wheaton and chatted with a couple of farmers who were plowing a field. I told them what I was up to and they confirmed that we were standing on the roadbed, visible as a broad strip of gravel through an otherwise green field. Then one of them pulled a tie plate out of the bed of the pickup—the plow had turned it up 40 or 50 feet from the roadbed (Photo 9).

Outside Fostoria, the railroad ran on a long, curving berm that intersected the road. Its path was marked by a thick line of white wildflowers growing along the top, making the sweeping curve plainly visible in the field (Photo 10).

On our last one-day trip, I figure I saw about half the roadbed of the railroad where it went through towns, or paralleled or crossed county roads, which are laid out in a grid without regard to the contours of the land. Next time, I hope to spend several days driving back roads, talking to farmers, tramping through fields, and tracing the entire route from Leavenworth to Miltonvale.

Wheaton, according to the Quastler book, was added to the KC in 1884. At that time it had an elevator, three general stores, blacksmith shop, post office and a few homes – a lot of promise.. It apparently didn’t have a depot but a wooden platform. The KC ran east west through Wheaton. Nine miles east, Onaga had a Kansas limestone depot but there is no trace of it now. You can see the right-of-way approach. amid some trees. Nobody that I met in town knew anything about the KC. They barely remember the UP that took over the KC, The last time I visited, the UP was building a new double track north south segment through Onaga, up to the Nebraska main line. But it looked like what remains of the town will see few benefits, except if you like train sounds.. I’d be curious if you find any KC traces on your trip.

I found this absolutely fascinating and hope to at Wheaton to our next drive south through Kansas because of this article. Thanks for sharing.

I never thought I’d find another Kansas Central “explorer.” My Oct. 2014 cover story in GR mentioned my Kansas and KC connections and a recent article on my gravel table showed a picture of my Miltonvale depot. The Quastler book and its photos have been my source for modeling plus by driving expeditions around northeast Kansas. Your use of satellite mapping is way beyond my silly driving trips to find the old right-of- way. As you know, the Kansas grid plan means you drive west from Leavenworth along what you think was close to the old route and then start zigging and zagging. The Winchester, Valley Falls, and Holton set ups were easy to find but I discovered the Larkinburg elevator by accident since it isn’t mentioned in the book. The original track route is visible there but many sections seem overgrown with trees. Farmers seem to plow using the old embankments as a border. That’s probably how they sold off the railroad land. My father’s family was from Seneca, Kansas beginning in 1870. The Kansas Central ran 15-20 miles south of Seneca back then and likely competed badly with the standard gauge StJ.&GI out of St. Joe. But the romance of the KC narrow gauge on its wobbly tracks that never made it to Denver and the riches of the Rio Grande country became a fascination for me. I’d like to see some of your satellite tracking and hear more about your research and Kansas connections. My Bachmann Mogul with KC markings is close to the original “102.” I asked Bachmann why they chose the KC paint job but they never answered and it’s not produced anymore. Anyway It’s a pretty loco and it got me interested in this rare and colorful history.

Great article! I also love tracing old rights-of-way. Thanks for the tips on using Google maps. In the 50s my father pointed out berms south Hwy 16 in southern Wisconsin that he said were the right-of-way for an interurban line from Milwaukee to Watertown that had be been pulled up years before. They are probably still there.

I enjoyed the article very much, Vance. I spend much of the year in Charente-Maritime in France where there was an extensive metre-gauge system before 1950. Lots of the stations survive and much of the grade has become rural roads. I use Google Earth and the French Géoportail website to trace the old alignments. I have shared my discoveries on the French forum http://www.passion-metrique.net/forums/index.php which helps me to improve my French language and get to know other like-minded people.

Great article. Living in the hills of East Tennessee I also have become a sleuth searching for long abandoned rail lines. Living in hilly terrain makes it somewhat easier than in the plains. Cuts and level roadbeds make following the routes of the long abandoned rail lines relatively easy. One technique I use is to look following a light snow. It is amazing how an old roadbed shows up with a slight layer of snow.

A scary thought is that I am old enough to remember some of the abandoned lines. 🙁