Note: Links to downloadable files are at the end of the article.

Solidworks program

I again will be using Solidworks as the CAD program but you can use any CAD program to build yours to your specifications.

The support pole has been painted a shade of gray and the signal itself has been masked off to prevent overspray (photo 1). (Note: It really is gray, not the color that came out of my camera!)

Everything on the signal pole is now ready to put together.

This project, like many of mine, is going to use a single, type 18650, Li-ion cell for power (photo 2). This cell will supply 3.7V at between 1500 to 3500mAH of current. (The exception is LiFePO4 at 3.2V.) The cells are fairly inexpensive due to their extensive use in commercial products, such as the Tesla Model S, autonomous robots, and LED flashlights. You can get two 18650 cells and a charger for about $7.00 from Walmart.

(Post note: Now that the solar cells have arrived; they do not measure 100mm x 50mm. They are 103.2mm x 47.9mm, so I have to lengthen the extruded cut to accommodate the extra 4mm. They are also not 3mm thick in total. The wiring needs to be accommodated as well, so I will include another extruded cut and a hole for the wiring.)

The solar panel will be at an angle for optimum, fixed, collection. For my location the angle needs to be 27.5°. A coupler will be needed to attain that angle and, since I will use the same brake line as the support for the solar panel that I did for the signal pole, the coupler needs to fit over the brake line. One end of the coupler will be mounted directly to the solar panel frame.

Here are the components for my solar panel (photo 7). As shown, there are four parts: the frame itself (frame.stl), the solar panel, glass, and the frame cover (frame top.stl). The ABS parts will be painted first, then I will put everything together.

However, I first need to cut off the supplied connector on the solar panel and glue down the wires to provide some mechanical relief. I used a hot glue gun, which works fine (photo 8).

Once the wires have been secured, the connector cut off, and the frame painted, it’s time to start putting everything together.

Next, the glass goes over the top of the solar cell inside the frame. I used GE Preminum Silicone Glue along the edges of the frame, then placed the glass inside. Try to make sure the glass is sealed against the environment.

With the support pole and the angled joiner that was printed earlier, the solar panel is now complete and ready to hook up the electronics and plant in the ground (photo 11).

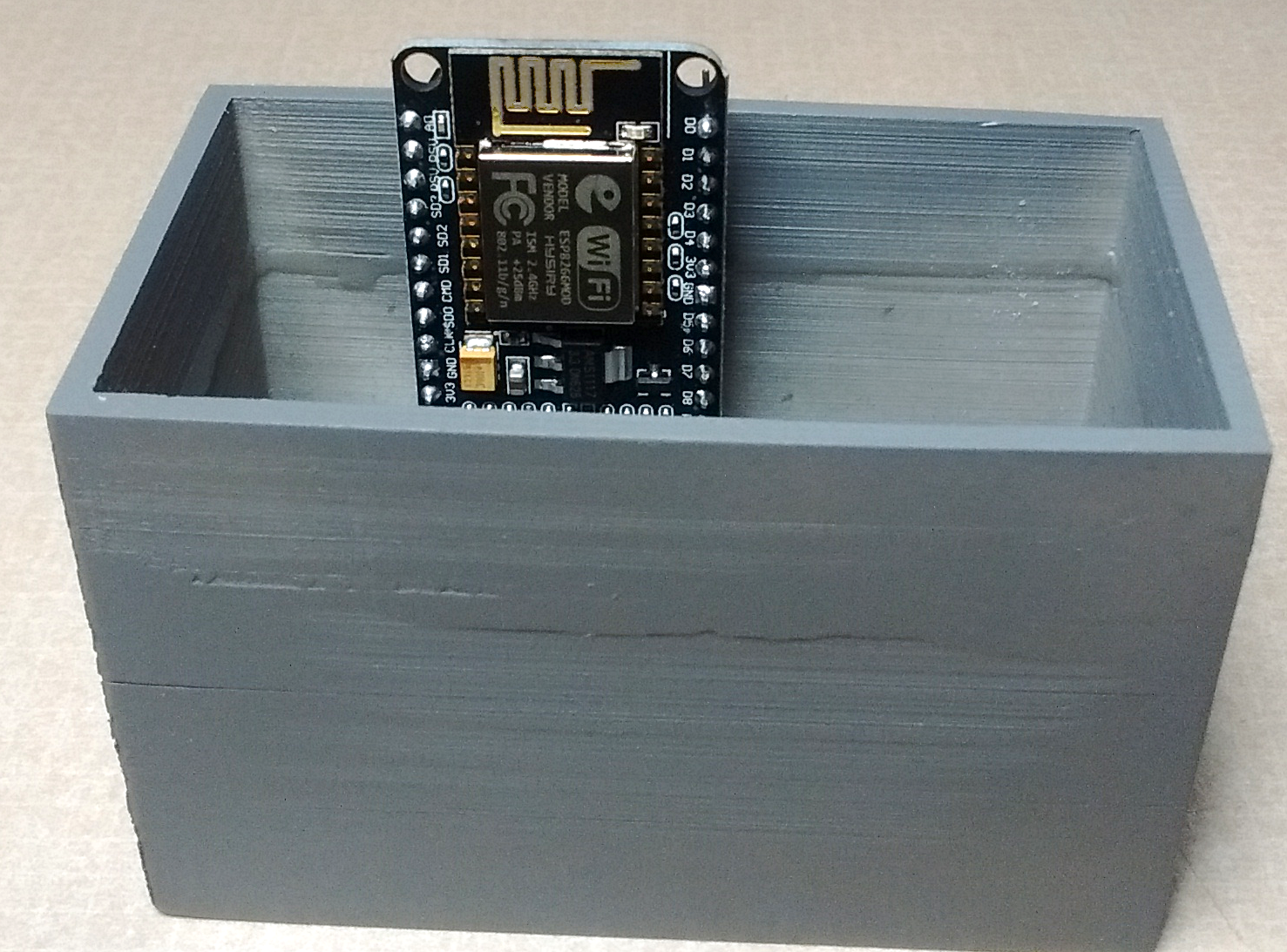

Since the signals are going to be automated, I need an equipment box to hold the battery, constant-current sources, and the WiFi. First, there are several things to consider:

1. Keep the battery below ground level.

2. Make the box high enough to make sure the WiFi antenna has a clear view of everything above ground level.

3. Make the box long enough to hold the 18650 battery.

Since it needs to look like an equipment box, I will need a concrete pad like those that equipment boxes usually sit on. (Note: you can hide the electronics just about anywhere — an old building, a signal hut, or anything large enough to accommodate the components. The solar panel could be fixed to the roof of a nearby building but, since I don’t want to keep tearing up wiring while I am weeding, I chose the equipment box to keep everything within a short distance of the signal.)

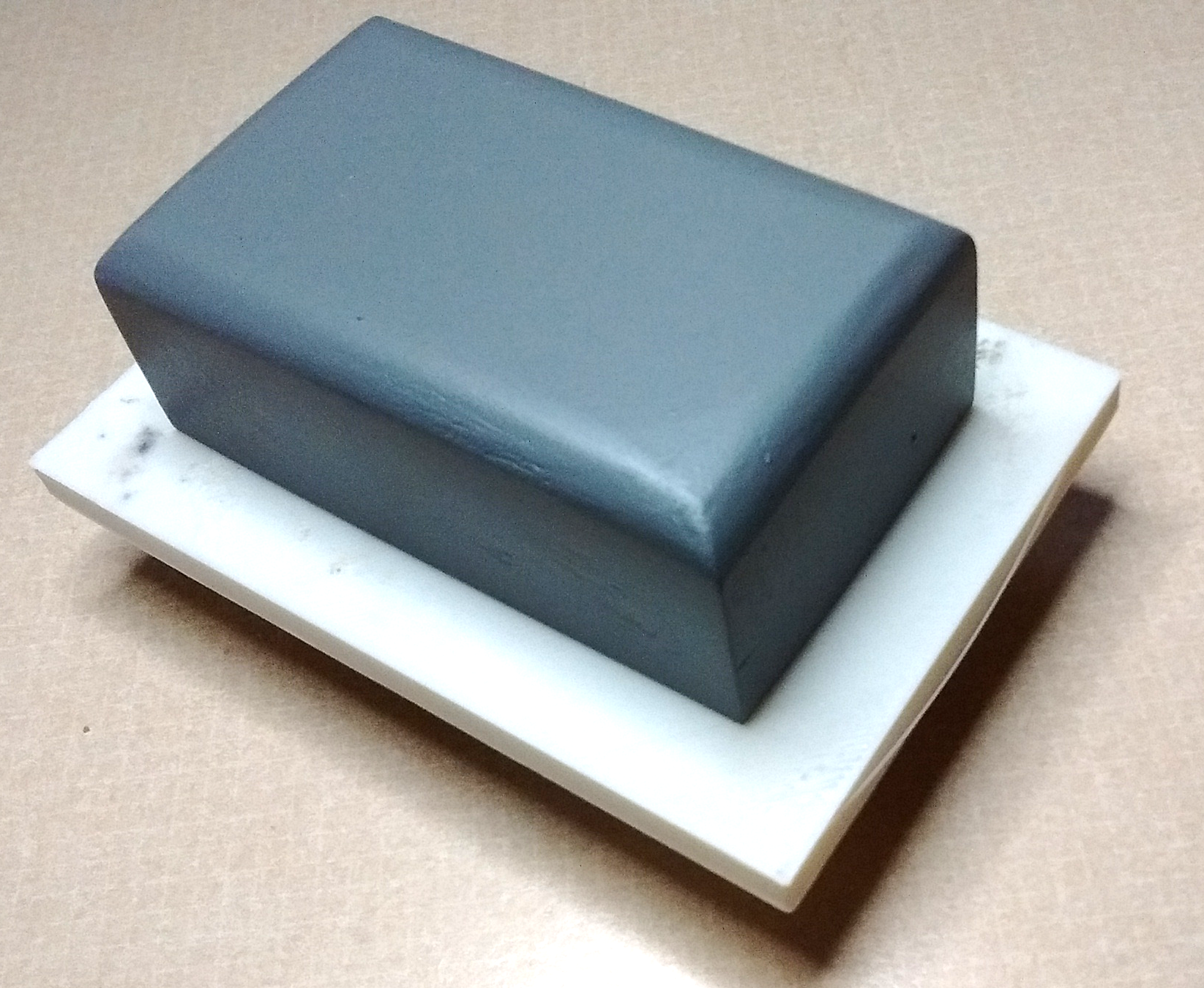

As is typical with ABS filament, there was some cracking (photo 12) and the vault completely separated in my hand while cutting off the flashing (photo 13).

I glued the broken vault together using CA cement, with clamps to keep everything as square as possible. The separated portion was filled with CA glue and sanded smooth