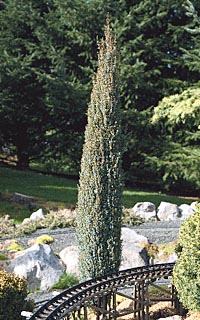

Are you practicing? In the last issue, we discussed the need to jump into the garden, shears in hand, and take a stab at pruning our needle-leaf conifers, such as spruce and false cypress, to create pointy, airy cones. Illustrations showed starting points and steps for finishing the scale tree; by following an illustration, you know when you’re done, just as in building a model structure. Over and over, year after year, we practice keeping living scenery manageable and out of the way of oncoming trains.

Woody broadleaf shrubs, whether evergreen like boxwood or deciduous like maples, model a different style or shape than our cone-shaped conifers, and require a new look at the role they play in the scenery. Most railway gardeners, such as the Kollmanns (photo 1), like to plant umbrella-shaped trees in town to shade buildings and keep scale plastic figures cool. Without our attention, the greenery could turn into fat bushes, hiding those buildings and townsfolk. Finally, we’ll take a look at how to clean up herbaceous perennials, including grasses.

Open a canopy from a sphere

Broadleaf means “not needle-like.” The scale purists are already whining, “Too big!” But perceptive modelers, like the Mortillaros, use the photographer’s trick of placing trees with larger leaves to hang in front of their mid-field scenes. This gives the viewer perspective and the sense of sharing the same ground as the artist (photo 2). In other areas, broadleaf “trees” could hide a fence or other 1:1 object.

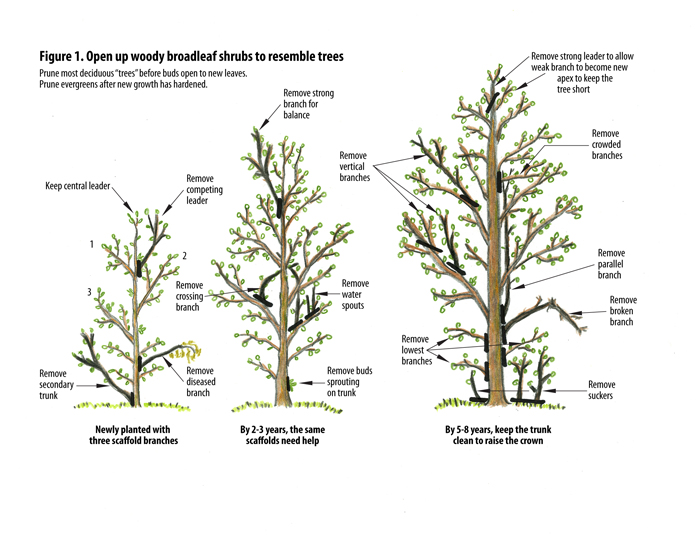

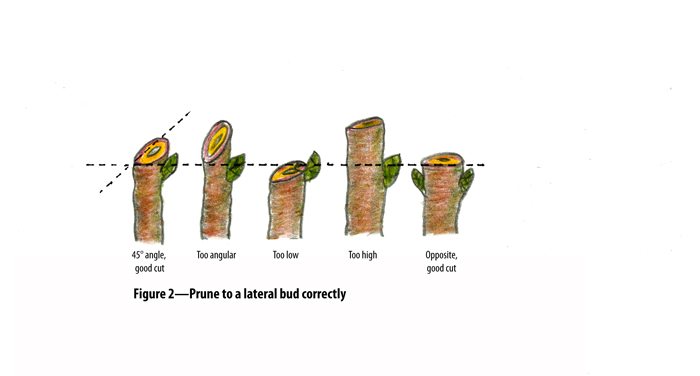

To make the lower branches (trunk) visible and the top ones lush, think of the lowest trunk-like branches as scaffolding or supports for the roof of finer branches bearing the canopy of leaves. Photo 3’s specimen boxwood shows how the Sommers divided the trunk near the bottom into interesting gnarled arms reaching up and out to hold up the top. When younger, it might have looked similar to the Millers’ boxwood in photo 4. Both boxwoods have been pruned of lower branches, crossing and crowded branches, and tips that shoot for the sky. Figures 1-2 show how cuts may keep the plant open and small throughout the life of the railway.

Pinch back perennials

Herbaceous perennials live year after year but die back to the ground in winter. When low temperatures kill the stems, the flattened tops of the plant can act like blankets to protect the roots from excessive cold and promote self-seeding. More importantly, stems act like mulch to prevent repeated freezing and thawing, which heaves poorly rooted plants up and out of the ground.

At the end of winter, prune or pull away the dead material to see green sprouts for the new season. In warmer climates, perennials can be pinched or pruned back after blooming, relieving the plants of dead flowers and broken stems for a tidier look. Some perennials, like heather, require pruning (deadheading) immediately after blooming to encourage next year’s blooms (photo 4).

Get into grasses

It makes us smile to see how seasoned railroad gardeners have solved some problems, owing to their many years of dealing with the same issues. Here are two solutions for perennial grasses.

How many times have you seen a worn tractor lying fallow in a forgotten field? That’s how the Altmans pictured their peaceful Canadian farm in photo 5. The Johnsons learned how to deal with bird-planted lawn-grass “weeds” next to their depot—they just shear them with scissors to keep the look in scale (photo 6).

Tidy up

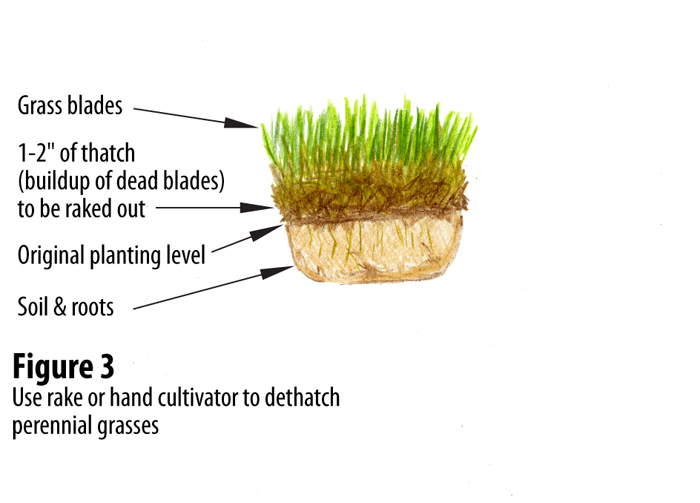

Keep your pruners handy when visiting the garden. Deadhead spent flowers. Use grass trimmers for groundcover. Dethatch grasses (figure 3). Pull out dead leaves from between branches with your gloved hand. Shake or knock the upper trunk a bit to allow loose, dead defoliation to fall out. It’s okay to leave an occasional lifeless tree or branch; it’s only natural and provides a perch for dragonflies and small birds. But be aware that most gardeners’ eyes will repeatedly fall on that deadness. Some people think there’s a best time to prune out diseased or dead wood, and there is—any time.

Let the sun get into branches to light up your scenery. With each pruning experience, the way to best care for your growing landscape becomes more obvious. It’s living art. As Neitzsche declared, “We have art so that we shall not die of reality.”

Prune with a purpose

“Open up” the tree to let in goodness:

• light for photosynthesis

• air for fungus-free leaves and stems

• water for hydration and cleaning off pests

• space to let defoliating leaves fall

• aesthetically balanced shape resembling a tree, not a shrub.

On an “opened up” little tree, one can imagine a scale bird flying down to perch on one of the shelf-like branches.

How do you prune your broadleaf trees and groundcovers?

Gary Everitt

Salem, Oregon, Zones 8-9

Dwarf burning bush

Last year we had such a beautiful early spring that most of the plants produced leaves and flowers much earlier than usual. I didn’t have an opportunity to prune until May. I prune according to the schedule I was told by an orchardist years ago: “The best time to prune is when you have the time.” So I have been known to prune any time of the year, but I usually start pruning the miniature plants in the spring after the branches have a huge growth spurt. Sometimes (read “usually’) a long rainy spring up here can put that off until the new growth is pretty long and after the dwarf Alberta spruce have already passed their new-growth soft stage. Our burning bush (Euonymus alatus ‘Compactus’, Zones 4-9) gets a big growth spurt in the spring, so I cut it way back. This year I severely pruned it back to give clearance for a streetcar on a new trolley line that I installed behind the diner.

Ray Turner

San Jose, California, Zone 9

Shrubs and thymes

Shrubby cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa var., Zones 2-9) can be maintained tree-like by thinning and removing low-growing branches every few months in the growing season. It blooms in the spring and all summer. Cotoneaster naturally wants to be a bramble, so it requires monthly pruning to open it up and remove branches growing downward. In the spring it fruits nice “apples” but I’m not convinced they are worth the pruning effort.

Elfin thyme grows thick with time and just needs shearing around the track every few months.

Woolly thyme sends out runners, which will root if left alone and require cutting off near the track.