1:32 scale, gauge 1, live-steam Royal Hudson

Accucraft Trains

33268 Central Avenue

Union City CA 94587

Price: $4,285

Web site: www.accucraft.com

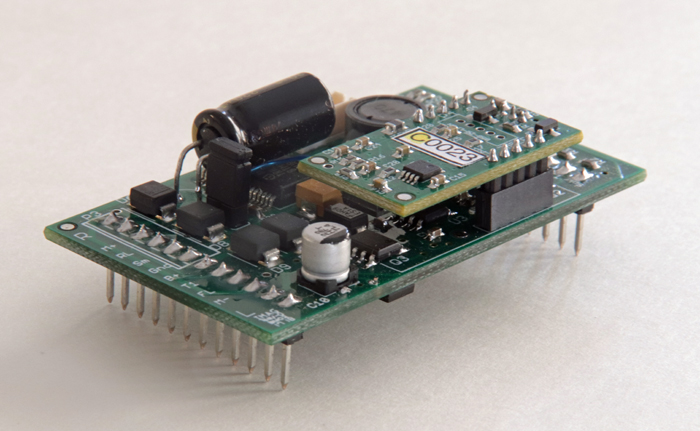

All metal, live-steam model of Canadian Pacific Royal Hudson; internally fired, multi-tube boiler; alcohol fired (gas firing also available); Walschaerts valve gear controlled from the cab; sprung drivers; equalized front truck; sprung rear truck; sprung, six-wheel tender trucks; two safety valves; throttle; blower; pressure gauge; water glass; whistle; bypass valve; axle pump; hand pump in tender; displacement lubricator; working cylinder drain cocks; instructions and elementary tool kit included; minimum radius, 10′. Weight: locomotive, 17 pounds; tender, 7 pounds. Dimensions: length (locomotive and tender), 343/8″; width, 4″; height, 61/8″. In 1:32 scale this works out to 91’8″ x 10’8″ x 16’4″, respectively

Pros: High level of detail; high fidelity to prototype; excellent paint and graphics; high level of sophistication; fully configured; smooth running; easy to handle; can be kept in steam indefinitely

Cons: Very little swing on front tender truck; only one drawbar hole-tender sits a little too far from locomotive; difficult to light

Our review sample is a model of #2860, one of the last Royal Hudsons built for the CPR, in June of 1940. This last batch burned oil (previous engines burned coal). The prototype has been preserved and is running today.

The model is an accurate replica of the prototype, complete in nearly every visible detail. It fully captures the prototype’s distinctive streamlining. Paint and graphics are excellent. The engine is available in three different liveries. The one reviewed is the engine’s “in service” paint scheme. The tender is connected to the engine via a simple drawbar with just one hole. This positions the tender a little far from the locomotive. A person with a drill press could easily add another hole.

The wicks on this engine must be packed by the purchaser. Wick material, which appears to be some type of ceramic fiber, is supplied and an insert describes the process, which involves removing the rear truck and a brace to get at the burner.

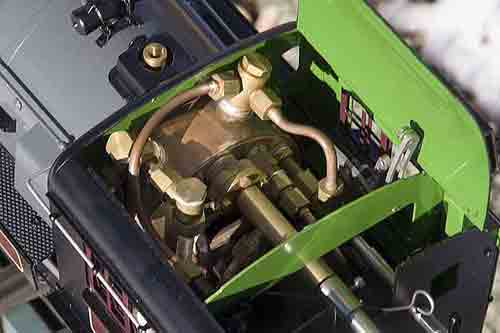

Mechanically, this is a complex and sophisticated locomotive. It sports just about every fitting possible, including a whistle concealed under a running board. The cab is crowded. The pressure gauge, on its side, faces out the left-side cab window and control levers protrude from the back wall of the cab. The cab roof lifts for access.

The tender contains the fuel tank, a water reservoir, and a hand pump for the water. The fuel tank utilizes the “chicken feed” system and has an open/close valve on the top. To attach the tender to the engine, you must first connect the water and fuel lines, as per the instructions.

Preparing the engine for a run is straightforward, so I won’t go into detail here. A tool kit comes with the engine that includes syringes, nut drivers, a pump handle, and some extra screws.

Running a locomotive of this complexity and sophistication is not for the faint of heart, nor is it for the inexperienced. Once the engine is fueled, oiled, and watered (using the tender pump), a suction fan (not included) is placed in the stack. I found the fire fairly difficult to ignite. You open the fuel valve, then, when the wicks are soaked, light the fire through the firebox door, as the bottom of the burner has a plate to restrict air flow, making the burner inaccessible from that direction. Lighting through the firebox door is awkward, as the door is placed near the floor of the cab (in the usual place), but the cab is quite crowded and the back of the cab is enclosed, as per the prototype. A wire attached to the firebox door allows you to open and close it. You have to stick a lit igniter down into the cab, then into the firebox to light the fire. I tried using my usual igniter-a length of stiff wire with some wick material at the end, soaked in alcohol, then lit. I couldn’t get this far enough into the firebox to actually light the fire. (To check if the fire is lit, a dental mirror is very handy.) What you really need, and what I finally had to go and buy, is a butane barbecue lighter. You thread the end of it into the cab, between the fittings, and get the nose as far into the firebox door as you can. You leave it there for 10 seconds or so, at which time the fire will be lit. The suction fan is turned on after the fire is ignited.

The instructions say that it will take about seven minutes for pressure to come up to 20 psi. It took around 15 minutes on our test run, but this may have been due to weak batteries in the suction fan or the coldness of the day. Once pressure finally came up to about 20 psi, the fan was removed and the engine’s blower turned on. From then on it was smooth sailing. Pressure came up rapidly to the blowoff point of 60 psi. As per the instructions, I put the engine in gear, opened the drain cocks, and cracked the throttle. The engine moved off at once, with water and steam escaping from the cocks-very impressive. After a few yards, I closed the cocks and the engine was off on its own.

Performance was all one could ask for. The locomotive runs smoothly and powerfully. It will run faster than you want but is easy to throttle down. I was concerned about the lack of movement in the front tender truck, but that proved not to be a problem (on my track, at least-minimum radius 13′). The ambient temperature was in the low 40s and the steam effects were great. The engine ran smoothly in both directions. The axle pump slowly increased the water level in the boiler, as it should. With practice, you should be able to learn where to set the bypass valve so that the water level remains constant. With an engine of this caliber, keeping it in steam all day is no problem.

Shutting the engine down presented its own problems. The instructions suggested using a CO2 dusting can to extinguish the fire, which is what I did. It worked fine. The instructions also say to blow down the boiler. The alcohol-fired engines, however, do not have blowdown valves (although I’m told the gas-fired engines do). The only way to blow it down, once the fire it out, is to open the blower, which I did. I also emptied the tender of its remaining fluids and gave the engine a wipe down.

This locomotive, when all is said and done, is a fine model of a classic prototype. It runs very well indeed and is a strong puller. Due to its complexity, I cannot recommend it as a beginner’s engine. However, if you have had some steam experience, you’ll find running this

locomotive a pleasure.