iMax Reverse Loop Module

Massoth Electronics

6585 Remington Dr. Suite 200

Cummings GA 30040

Price: $128.50

Web site: www.massoth.com

15-amp capacity, automatic reverse-loop detection and direction-control system for DCC or DC operation

Pros: Non-shorting detection eliminates arcing and pits that can damage wheels and track; works with DCC and analog DC (with extra power supplies and switches)

Cons: Black-and-white photo of wiring in instruction book is ambiguous, making following it for installation impossible (the on-line color version clarifies things); vague instructions for analog DC operation

Reverse loops have always been problematic for track-powered railroads. There have been many schemes over the years to make the reversing of the power automatic. Some use magnetic sensors, others detect the short circuits that fried many a fuse in my youth, quickly switching the power the other direction. Massoth’s automatic detector is an advancement of that technology.

The problem with detection circuits that trigger on shorts is that they require a short to trigger it. No matter how quickly it detects the short and changes the polarity, there’s still an instantaneous arc across the wheel to the rail, which pits both the wheel and the rail. Over time, these pits build up and the wheel becomes pretty useless for picking up electricity.

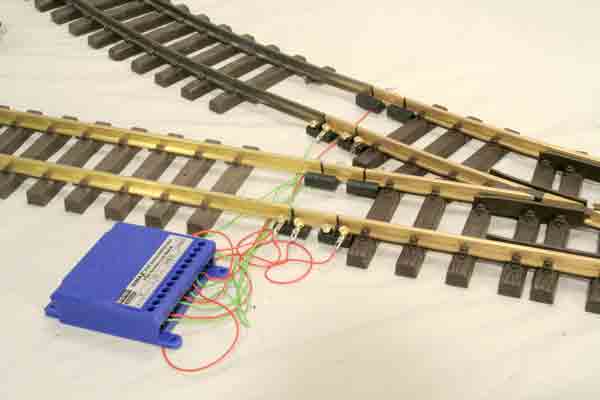

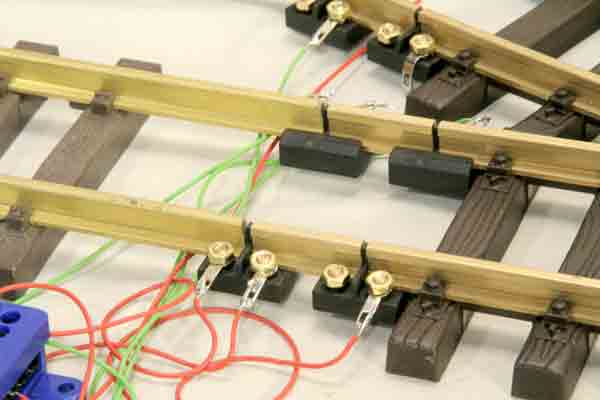

Massoth has solved this problem by doing something different. Instead of detecting a short, it uses a very small section (about 1″) of rail that is electrically isolated from both the reverse loop and the trunk line. When a locomotive comes in contact with this isolated section, the wheels transfer power from the energized rail to this insulated section. The insulated section is connected to sensors in the “little black box” (it’s actually blue), which compare the polarity of the voltage on one side of the insulated section to the other. If it’s reversed, the box changes the polarity of the power to match. There’s no short to cause arcing, thus no damage to the wheels or track. In DCC operation, you can even have two trains in the loop at the same time, since your direction of travel is independent of the track polarity.

The revering unit measures around 2″ square, and around 1/2″ tall. It has screw terminals to make connecting the wires simple. There are four “in” track inputs, two “out” track outputs, four sensor inputs, and an external-power input for regular DC operation. The instruction manual describes various wirings for the myriad ways to hook up this unit. My only complaint is that the photo showing how the wires are attached to the sensors is hard to decipher because it’s printed in black and white, and you cannot tell which colored wires really go where. I had to go to the company’s web site and download the color PDF version of the manual to see what was really going on. Once I had that figured out, installation was simple.

The insulation clamps that join the rails are designed for code-332 rail. If you use smaller rail, you’ll need to supply your own insulated rail joiners.

The instructions say the unit works on 14-27 volts DC. I hooked the unit up per the photos, including some diodes that the manufacturer recommends including when there’s a great distance between the track sensors and the control box. Evidently, the voltage drop across those diodes was enough to lower the output of my power supply to the point where the unit would not function properly. I removed the diodes from the circuit and all worked as advertised. The relays inside the box audibly click as it changes polarity so you know it’s working just by listening. It has a rated capacity of 15 amps so I don’t foresee it being overloaded by even the most aggressive installations.

The reverse unit works for a single reverse loop or wye; the book has wiring diagrams explaining installation for both track arrangements. If you have a double-reverse-loop set-up, you’ll need one module for each loop.

The unit also has other operational modes, including one that works by detecting shorts, and working off of regular analog DC track power. The short-circuit method works as advertised, though the strong-point of this unit is that you don’t need to use that. I did not test the analog DC operation, as I didn’t have any switches or magnets to attach to my locomotive to test the circuit. I do wish the instructions were a little more detailed as to what, exactly, those switches and magnets have to be in order to function.

Massoth recommends that the reversing unit be kept out of the elements. While the sensitive electronics are sealed within the box, the screw terminals are not, and could corrode if exposed to moisture. (Housing the unit inside a lineside building, for example, would provide sufficient protection.)

It’s been quite some time since I had anything to do with track power, reverse loops being one of the primary reasons I abandoned that method. I have to admit, though, that I’m impressed by this new technology to facilitate some of the more tedious and problematic aspects of track power. With this unit, I’d have no worries designing a reverse loop into a track-powered railroad design. I really like the “no short” aspect of this. I don’t know how much damage a brief short circuit could do to the modern electronics that control our trains, but if I can eliminate that as a potential cause for trouble, I’m all for it.