The hobby of model railroading looked very different when Al Kalmbach launched The Model Railroader in 1934. Train sets were more toys than scale models, cars were made out of wood and cardboard, and practically everything had to be scratchbuilt or at least assembled. Different manufacturers’ trains ran on different electrical currents, there were several competing coupler systems, and shredded asbestos was considered a great choice for ground cover. (We no longer recommend that.)

To borrow a line, we’ve come a long way, baby. Our model railroads are more realistic than ever, both in how they look and how they run. A lot of that is thanks to the National Model Railroad Association, whose Standards and Recommended Practices made it possible for products from any manufacturer to work with those of any other. But equal credit goes to the manufacturers who saw the chance to revolutionize the hobby and took it. Here’s a look back at some of the innovations that changed model railroading into what it is today, presented in order of introduction.

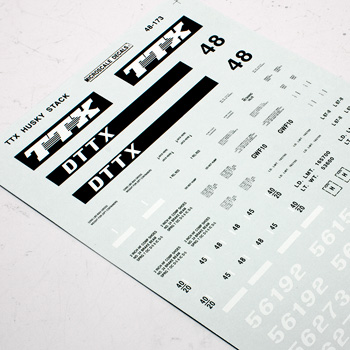

Water-slide decals

Decals predate steam railroads by about half a century. The technique was developed in France in the 1750s as a way to use tissue paper to transfer engraved designs to ceramics. But pre-printed water-slide decals were in use in the hobby in the 1920s. Lionel was using water-slide decals to letter its products in 1937, and cars lettered with “decalcomania” (an early term) were advertised in the earliest editions of MR. As time went on, businesses offering custom-printed decals brought realistic graphics to the casual hobbyist. Today, anyone can print custom color decals on their own computer printer.

NMRA standards gauge

The revolutionary thing about this product isn’t the product itself, but rather what it represents: National Model Railroad Association Standards and Recommended Practices. When the NMRA was founded, there was no standardization between manufacturers. One company’s wheelsets wouldn’t necessarily fit on another company’s trucks. Each maker’s locomotives had their own power requirements (some ran on direct current while others used alternating current). When Al Kalmbach, hobby retailer William Walthers, Milwaukee mayor Frank Zeidler, and others gathered at that first NMRA national convention in Milwaukee in 1935, settling on standards for the different scales was Job 1. The hobby we know today wouldn’t exist without the work of the NMRA.

Onboard sound

Modelers have been trying to put realistic railroad sounds in their models nearly as long as the hobby’s been around. Lionel started equipping its three-rail O gauge locomotives with air-driven whistles in their tenders in 1935. Model Railroader published an article on how to pipe a more realistic sound signal to a speaker in a locomotive tender in May 1959. But that was a homebrew solution. This system was “perfected,” in the words of a July 1972 MR product review, by Pacific Fast Mail. Its system came with a control panel and a speaker module to be installed in a locomotive tender. Today, prototypical sounds are generated by tiny Digital Command Control decoders.

Hobby paints

Being able to purchase hobby paint in authentic railroad colors is taken for granted these days. But that wasn’t always the case. Al Kalmbach used to color his scratchbuilt cars with thinned-down printer’s ink. The Testor Corp. first advertised its new line of hobby paints (in 14 colors) in the October 1946 MR; Floquil’s Hobbycraft paints were announced in February 1947. What distinguished hobby paint from regular paint was its thinner consistency and finely ground pigments, which enabled it to cover evenly without obscuring molded-in textures. Even when hobby paint became readily available, it didn’t come in a wide variety of prototypical colors. Formulas for mixing the basic colors into accurate railroad colors were passed around between hobbyists like treasured family recipes. Today, practically any desired railroad color is available pre-mixed at the hobby store.

The airbrush

The airbrush was first developed in the late 1800s. It didn’t catch on quickly with the hobby market, though. Model Railroader didn’t run its first article describing the use of an airbrush until March 1959. But the development of better hobby paints, with a consistency thin enough to work in an airbrush and still cover effectively, made it more useful, and it caught on quickly. No camel-hair brush, however fine, could achieve the smooth, even paint coverage of an airbrush.

Weathering chalks and powders

Weathering, turning a pristine model into one that looks like it’s been working hard out in the sun, rain, and sleet for years, is an art form. So it’s appropriate that one of the most useful weathering products came, like the airbrush, from the art world. Artist’s pastels, chalk-like drawing sticks that come in a rainbow of colors, could be shaved into a powder that modelers applied with a soft brush. The effect is softer and easier to build up in subtle layers than paint. Now, hobby manufacturers offer finely ground pigments in colors like rust, dirt, mud, grime, and soot, mixed with dry adhesives that make them stick even better to our models.

Flextrack

Though many of us associate the early days of model railroading with tubular sectional track, flexible track is older than you might think. It wasn’t the flextrack of today, with realistically textured plastic ties and molded tie-plate-and-spike detail, but rather extruded steel or brass rail stapled to fiber ties. In a full-page display ad in the June 1938 Model Railroader, Mantua touted its HO scale Ready-Laid Track as being able to curve to radii as small as 20″. Atlas offered a similar product. It wasn’t foolproof; Linn Westcott complained in a 1945 article that the clips on his Mantua track were so tight that he couldn’t bend it. Still, it was a great leap forward from the rigidity of sectional track. Flexible track freed modelers to build the trackwork they wanted without the work of hand-laying.

X2F couplers

Though it’s maligned these days, the X2f coupler, also known as the “horn-hook” or “NMRA coupler,” was a great leap forward for its time. Before its development by an NMRA committee in 1955, a number of incompatible systems, including LaNal, Mantua, and Varney, competed for market share. The X2f had its own problems – it looked nothing like the prototype, it took a lot of force to connect, it wouldn’t couple on curves, it tended to cause derailments when backing, and the ramp-based uncoupling system was clunky. But it was cheap to make, so some manufacturers adopted it as a standard even before the NMRA did. The price helped the X2f hold its own even as the Kadee magnetic knuckle coupler was introduced almost concurrently. And just having a universal design was a vast improvement.

Kadee couplers

If it seems like magnetic knuckle couplers have been a part of model railroading forever, you’re not far off. Twin brothers Keith and Dale Edwards (the K and D of “Kadee”) introduced an HO scale mechanical knuckle coupler in 1947 – eight years before the X2f – and the Magne-Matic, still known and sold today as the “No. 5,” in 1956. Not only did Kadee’s version couple easier than horn-hooks, it featured “delayed uncoupling,” which allowed a car to be pushed with the couplers unhooked, dropping it along a siding where needed. No longer was uncoupling limited to the location of ramps. And though the early versions were oversize for the scale, they looked more like the real thing, too. Now that Kadee’s patents have expired, other manufacturers are offering their own magnetic knuckle couplers, most of which work together – a new de facto standard.

Styrene

“From the comments I have heard and read, the word ‘plastic’ is in the same category as profanity among model rails. This is plumb foolishness; you don’t know what you’re missing,” modeler Alan B. Armitage wrote in the August 1959 Model Railroader. Armitage would further press this view in a two-part article later that year, “The case for styrene.” Even then, he saw the advantages styrene offers: “It cuts easily with an ordinary knife, scribes beautifully, has no grain, can be drilled and tapped … and will take rivet impressions as well as any metal.” He also touted the material’s versatility, strength, and ease of gluing and painting. Who am I to argue with a man MR called “one of the hobby’s finest model builders?”

“Shake-the-box” car kits

Say “Ambroid” to any longtime model railroader and brace yourself for a rant about how modelers these days don’t know how good they have it. Like early structure kits, early car kits used to consist of an instruction sheet, a box of sticks, and printed-cardstock sides. Then styrene injection molding was developed. This revolutionary process, which could turn out model parts quickly, cheaply, and repeatedly from a single set of tooling, turned model rail cars from a craftsman’s work to a commodity. Before long, Athearn, Varney, Globe, Walthers, Model Die Casting (Roundhouse), and others were producing car kits with plastic sides and ends or even one-piece plastic bodies. Some were so simple to assemble that all you had to do was “shake the box.”

Cyanoacrylate adhesive

Most people remember first hearing about cyanoacrylate adhesive (or CA for short) from those memorable “Krazy Glue” commercials in the 1980s. (The brand first appeared in stores in 1973.) But the all-purpose, quick-setting adhesive was first marketed by Eastman Kodak in 1958. Before that, modelers looking to bond dissimilar materials, like plastic to metal or metal to wood, had to rely on two-part epoxy, a comparatively messy, slow-setting, and wasteful alternative. Cyanoacrylate adhesive not only made the assembly of mixed-media structure and rolling stock kits a lot easier, it probably also prompted the sale of a lot of acetone-based nail polish remover to sticky-fingered model railroaders everywhere.

Injection-molded plastic structures

Structure-building craftsmen used to scoff at modelers who built plastic structure kits. But injection molding made plastic come into its own. Finally modelers had an easy way to realistically represent brick, tile, shingles, and concrete block, as well as finely molded castings for windows, doors, and detail parts. Bachmann Bros. advertised its line of HO scale Plasticville structure kits as far back as 1952. Atlas, which had started out offering modeling tools, launched its line of structures with a styrene through girder bridge kit. Revell followed with an enginehouse that soon became a favorite of kitbashers and is still sold today. Soon, other manufacturers and importers like Con-Cor, Heljan, AHM, Walthers, and Vollmer joined them. Though the purists scoffed, styrene structure kits were here to stay.

Light-emitting diodes

You won’t find too many modelers using the phrases “grain of wheat” or “grain of rice” these days, unless they’re talking about breakfast. Those are the sizes of miniature incandescent lightbulbs that used to be used as model locomotive headlights, structure illumination, and trackside signals. But that would change with the introduction of commercial light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in 1962. We published our first project using LEDs in February 1971, a flashing grade-crossing signal. Since then, LEDs have been introduced in a variety of colors and smaller and smaller sizes. Today’s surface-mount LEDs are so small that Z scale engines can have working markers and ditch lights. Best of all, they last a lot longer than incandescent bulbs.

Ground foam and static grass

Most of us remember the terrain under our first train set as being the living-room rug. When we graduated to our first real train table, it might have been painted green, or if we were lucky, covered with green-flocked grass paper. Modelers in the early days of the hobby did wonders with plaster, sifted dirt, dyed sawdust, lichen, and even shredded asbestos. A product review in the July 1968 Model Railroader marveled at how realistic and versatile ground foam was at modeling grass, shrubbery, and tree foliage. A similar breakthrough came when static grass – short synthetic fibers – entered the market in the early 1970s. Electrostatic applicators would come along later. Both were vast improvements over dyed asbestos.

The internet

This one isn’t actually a product, nor is it model railroad-specific, but there’s no denying the impact it’s had on how we build our layouts. Before Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989, researching a prototype railroad involved going to the library and hoping it had the book you wanted. Buying your own copy of an out-of-print book required attending swap meet after swap meet, traveling to distant book shops, or even hiring a rare book agent. Railroad historical societies were great sources of information, but often too distant to be convenient. Now, thousands of pages of information, photos, and maps are available instantly.

Laser-cut structure kits

Wood structure kits have been around a long time, but they used to be of the “craftsman” variety, requiring the builder to do a lot of measuring and cutting before the glue even came out. A common term for such kits was “box of sticks.” In the late 1980s, firms like New England Structures, Micro-Scale Models, and Fine Scale Miniatures began offering laser-cut wood kits. We reviewed FSM’s first such kit in our December 1989 issue. Though similar wood kits featuring die-cut siding were offered earlier, computer-driven laser cutting reduced the cost of producing these kits, putting the realism of wood structures within the reach of more modelers.

Digital Command Control

There were model railroad command-control systems before the NMRA issued Standards 9.1 and 9.2 in 1993. The system that would become Digital Command Control was a licensed extension of one developed by Lenz of Germany under contract to European model makers Arnold and Märklin. Competing systems still exist today. But it was the NMRA standard that guaranteed decoder-equipped locomotives made by any manufacturer would work on a layout powered by any other manufacturer’s DCC base station. Digital Command Control brought a variety of advantages over direct current, not the least of which was the ability to control multiple model locomotives independently on the same section of track.

3-D printing

Just as laser-cutting had done with wood kits two decades earlier, the advent of inexpensive commercial 3-D printing services democratized the production of detailed metal and plastic parts. Now, producing the exact detail part, vehicle, locomotive shell, or structure you want is within reach of any modeler who has access to the internet and the patience to learn to use the software. And for those who don’t, entrepreneurs are offering custom design and production services. Prototypes too rare or obscure to make mass production viable can be made in small runs or individually.

Power on board, a.k.a. “dead rail”

A relatively new development whose impact on the hobby has not yet been fully realized is radio-control and battery technology. These developments are commonly known under the catch-all term of “dead rail,” since they allow model locomotives to travel, just like the prototypes, on non-electrified rails. The concept of dead rail isn’t itself an innovation; wind-up clockwork trains predate electric ones, after all. And both battery power and radio control have been tried before. But it’s only in the past few years that both high-density rechargeable batteries and control circuits have been miniaturized to the point where both could be installed in a standard-sized HO scale locomotive. We can imagine a future where today’s standards like power packs and layout wiring are things of the past.

I remember in the late 50’s finding my way into a hobby shop and seeing all manner of amazing things that would tease any 9 year old of the time… although I was originally there to acquire those plastic baggies of 1:72 scale German military tanks with the Airfix header card. On the other side of the aisle was … the trains. Gosh, those were such inspiring days leafing through the product catalogs and pamphlets, most two-color, but some full color. I look back now, especially after the reminders of this article at the progress we’ve made since, and think I am so very lucky to have experienced that era first hand.

And looking back I’m amazed at what I thought was great (well, it was then) compared to today’s offerings, but more so, notice that half my modeling is still stuck in the 60’s & 70’s. I read about “grain-of-wheat” bulbs and thought “Wuzzamatter with them?” … and then, uhhh, oh, yeah, right. Did anyone else try putting them into a model car build for headlights only to find the bulb kinda, well, melted the surround area? Or those Gloor Craft structure & car kits, or the superb LaBelle passenger cars that everyone knew that there was nothing better than wood, than wood, right? At least until, Roundhouse came out with their injection 36′ Old-timer cars in glorious reefer and boxcar designs. I was gonna argue something about that “shake-in-the box” kit, but, I’m seeing the light. The 40′ AAR box I wasn’t into so much cuz when I grew up (sorta) there was still plenty of RS3’s and OB and double-sheathed boxcars on the roads. I still prize my collection of all those models I have acquired over the decades because I’m still stuck in the past and they bring my a quiet comfort to my modeling.

Mind you… moving into Period Miniature structure kits. Dimi model, Gould and even FSM… well, yeah, the hobby just keeps involving to new heights. And buying those great Atlas HO diesel loco’s got better with the Kato drives and all the work of buying Detail Associates & Grandt parts to upgrade the models was just par for the course, if you wanted to show off something special. By the time I added up what I invested in the Atlas loco upgrade, I would’ve saved some coin and time, and just bought one of those Genesis or BLI loco’s you get EVEYTHING already installed with much better detail and function… even at those prices! When I finally broke down and bought a Genesis SD70ACe DCC Sound and fired it up… I was gobsmacked at the realism and sound!

Yup, the hobby sure has changed since 1964 when I started my first layout with an 0-6-0 Rivarossi side tank – which I still have and still runs – and the evolving continues. I so happy I’ve gone along for the ride 🙂

50 years ago, a project in California produced a set of module standarders that enable modelers from all over the world to bring their trains out into the public light and show people what model railroading was all about. There were a few portable layouts, but all components were restricted to that specific layout. What occurred at the Belmont Shore Model Railroad Club was a modular N-Scale layout and set of plans that change model railroading from decline to a thriving hobby that now uses modular standards to bring N and HO layouts along with other scales to just about every single train show. Without NTRAK, and Jim FitzGerald, model railroading would not be what it is today.