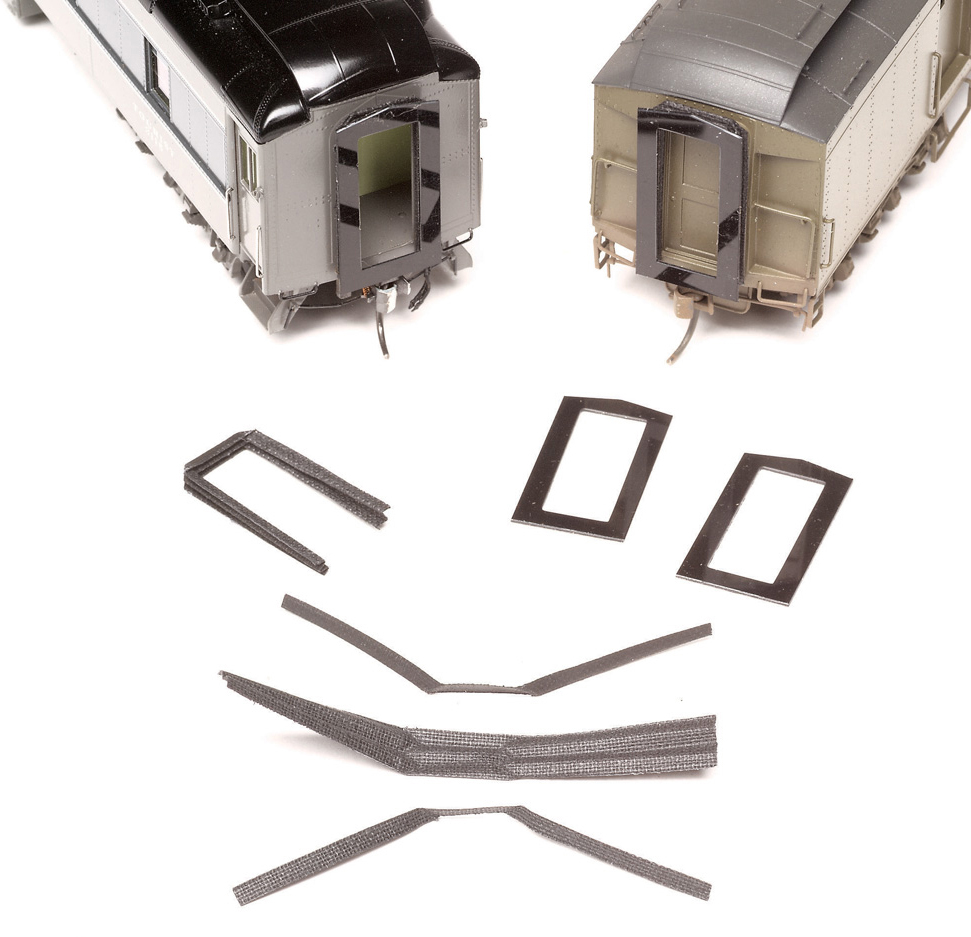

Diaphragms are bellows-like connections that enclose the space between cars for safe passage through the train. Passenger cars look naked without them, but they can be a pain in the neck if they don’t let cars negotiate all kinds of trackwork, or if they keep cars from coupling and uncoupling. I took my cue from Chuck Hitchcock, who found reliability in simple modifications he made to an old-line product.

Starting with Walthers no. 933-429 diaphragms, flatten out the folded paper bellows and use a steel rule and a sharp no. 11 blade to trim off one full fold. This lets the diaphragms fit between close-coupled cars. Then fold up the bellows again and rub hard along the folds with the steel rule to reduce their springiness. Chuck called this “taking the fight out of them.”

Finally, when assembling the diaphragm, make sure the burr left when the vinyl striker is punched out faces in toward the bellows. You can feel this burr by rubbing a finger across the striker; keeping it on the inside lets the striker slide smoothly against the next one. The sliding strikers let cars move freely though curves and turnouts whether being pushed or pulled.

The modified diaphragms don’t interfere with automatic coupling and stay tight on straight track. They will gap open slightly on sharper curves, but otherwise they look good. About the only way to manually uncouple cars with diaphragms is to take slack and pull one glad hand toward you with a wooden skewer. Since that may be possible only on the front track in a station, it’s best to plan for magnetic uncoupling.

From The Model Railroader’s Guide to Passenger Equipment & Operation (Kalmbach Books, 2006).