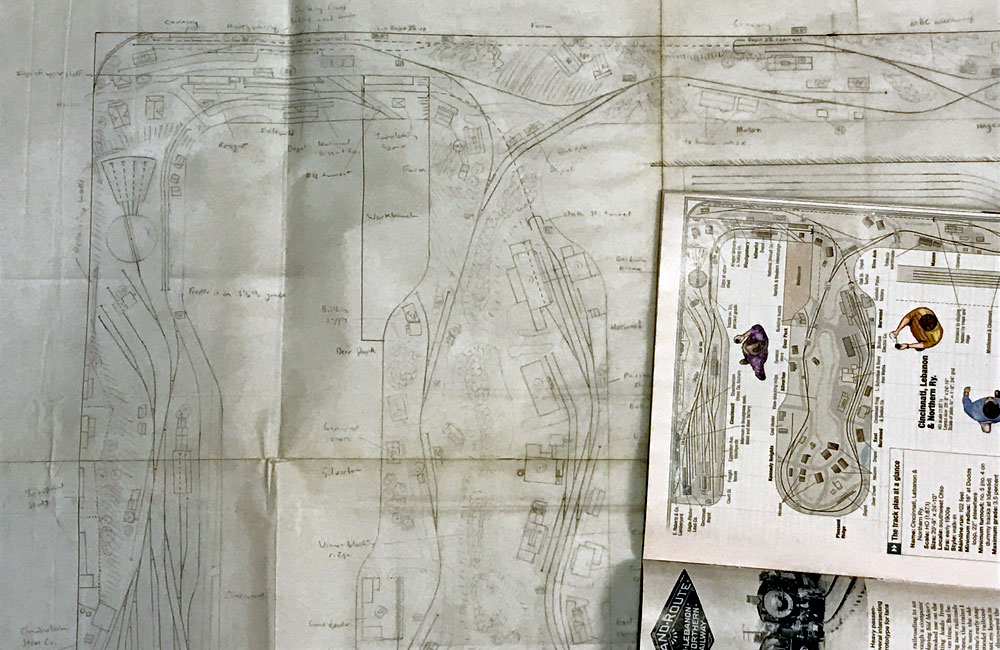

Today’s sketch was drawn long before Sketching with Steve was a gleam in anyone’s eye. It was 2008, and I’d been with Model Railroader less than a year. Finally, the resources to build my HO scale version of the Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern Ry. in 1906 were within my reach! I drew this track plan to fit in the 2½-car garage belonging to my then-fiancée, now wife, Traci, and was immensely proud when it was published in MR’s September 2008 issue. So let’s examine my mistakes in this track plan.

Luckily, this track plan was never built. When my mentor, MR executive editor Andy Sperandeo, looked at it, he just shook his head. Today, 13 years later, I see what I couldn’t see at the time, but he did. Let’s see what we can learn from my youthful mistakes. (I was just a callow lad of 43.) Don’t worry if you can’t read the photo of my faded drawing; I’ll link to a PDF of the published version below.

But first, I’ll practice a little self-care by listing the things I still think I did right on this track plan. By selectively compressing the long, boring, rural northern half of the layout into a shelf along the garage’s back wall, I managed to model the prototype’s entire 29-mile route in a space just under 21 x 25 feet, and still leave room for Traci to park her car. The track arrangements at Cincinnati and Lebanon are fairly close to the prototype, thanks to good diagrams in my reference book, Narrow Gauge in Ohio (Pruett Publishing Co., out of print). I included hidden staging to bring traffic in from the line’s northern connections. There’s a ton of operational opportunities all along the line, from depots and industries to team tracks and interchanges. I avoided putting the busy Cincinnati yards and industrial Norwood back-to-back, so operators wouldn’t get in each other’s way. And I understood that gentle curves that don’t parallel the benchwork edges look more attractive and interesting than ruler-straight main lines that do.

Now, let’s examine the mistakes in this track plan. First of all, it’s too crowded. Between Cincinnati and the wye at Blue Ash, the end of the commuter district, are seven named towns, four with depots and three more with passenger sheds. There’s just too much going on for this kind of space. As a result, both visual and operational realism suffer. The industrial area in Norwood is fine – in fact, it could be bigger – but the commuter stops at Silverton and Deer Park are only 3 feet apart! I should have added industries to East Norwood and modeled only two of the suburbs on the other side of the peninsula. That would let the commuter trains travel at least a few feet between stops.

Speaking of commuter stops, one thing I’m embarrassed to admit I didn’t know at the time was that stations always go on the main line. At many locations on this plan, I placed depots and passenger platforms along passing tracks, stub-ended spurs, and even an interchange. Likewise, there are a few spots where I have the main line going through the diverging route of a turnout. That’s not how prototype railroads did things.

A side effect of the crowding is that many of the team tracks and industrial spurs are less than 2 feet long. That’s too short even for the 34-foot boxcars of 1906, when the layout is set. Many spurs as shown would only be able to hold one car. And the only sizable passing track on the layout is at Norwood. Trains would be limited to the length of the siding at Blue Ash.

While it’s good that I included staging, it’s poorly implemented. Both the northern staging yard and the single muzzle-loaded staging track that feeds the Middletown & Cincinnati interchange are under the scenery and pushed back against the wall. Fiddle staging would be impossible, and if there were a derailment back there, reaching it would be difficult.

But the biggest problem with the track plan is the one that made Andy shake his head. Do you see it? It’s under the Blue Ash wye. In my effort to keep the Cincinnati and Norwood operators from bumping into each other, I flipped the industrial district to the other side of the peninsula. This makes it impossible for an operator to follow his train along the line, since twice he must walk around from Idlewild to Blue Ash while his train moves out of sight.

So how to fix this problem without crowding the aisle? One idea would be to place Norwood along the back wall (to the right of the plan), put the Blue Ash wye where Lebanon is, and extend a peninsula into the center of the room from there, with rural Mason and Hageman on one side and Lebanon on the other. Exposed staging could then extend along the front wall, on the left. This would eliminate the space for my wife to park her car, but we’re talking about improving the track plan, not my marriage.

The other way would be to flip the plan south-to-north. Put Cincinnati where Lebanon is, extend Norwood and the suburbs up the back wall, wedge the Blue Ash wye into the top-right corner, then wind the rest of the mainline along a peninsula branching off the top left. Operators would view the main line from the north side, contrary to the usual way of doing things, and losing the Montgomery branch isn’t ideal. But compromises are often necessary when dealing with what the dean of track planning, John Armstrong, called “givens” – factors that can’t be changed, like the size and shape of your layout space.

Oh, right, the difference between walk-in and walkaround layouts. A walk-in layout has aisles you can walk into, with layout on both sides. A walkaround is one where you can follow your train as it travels from one end to the other. A track plan can be both, but as published, my plan isn’t. It’s a walk-in, but not a walkaround because of that flip-flop on the peninsula. All clear?

Click here to download a PDF of Steve’s HO scale Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern track plan from the September 2008 Model Railroader.

Click here to download a PDF of Steve’s HO scale Cincinnati, Lebanon & Northern track plan from the September 2008 Model Railroader.

I too would suggest reading John Armstrong’s “Track Planning for Realistic Operation” and Bruce Chubb’s “How to operate Your Railroad”. The books are old, but do contain the essential things that are needed in order to create well working layout. Unfortunately none of the latest MR books level with those two.

What struck my eye was the lengths of passing sidings. There seems to be a generous passing loop at East Norwood but the loops at terminus stations are not in relation to this. The shortest passing loop dictates the longest trains one can run. There seems to be very few double passing sidings. Often one may run into situation that one has to hold a train at a station, and in addition to that, manage a two way passing. No-can-do here. I’d add at least one three through track station about midway the length of the layout. A good plan is to allow goods train to isolate itself into a group of sidings during switching to allow passing trains still — if one is desiring to have action at nearby stations while doing intensive switching at one station. The hidden sidings have no runaround facilities, why?

In MR trackplans as a whole I miss the fouling point marks of the turnouts, as it matters a lot when thinking about the length of passing trains. One can get too optimistic a view of the nicely drawn track plan only to notice that there is no way even a moderate length train can actually pass another anywhere.

One of the most fun and instructive features of John Armstrong’s “Track Planning for Realistic Operation” was the section where he took published track plans and suggested improvements. Glad you’ve picked up the ball, Steve. A lot of J.A.’s track plans had a lot of stuff crammed in and I have wondered whether this was meant to suggest possibilities. Tom Chatton

Sometimes prototypically correct design items don’t fit in reality. So it’s either fit them into available space, or leave them out.

I prefer the former.