John Allen’s Locomotive Weathering Secrets: Digging through back issues of Model Railroader the other day, I came across a short article about John Allen’s techniques for weathering locomotives. The January 1964 article features the work of several modelers, including Bill McClanahan and John Allen, and provides some tips on their practices for painting and weathering engines. At that time, most modelers didn’t weather their trains, which was one of the reasons why John’s work stood out in the pages of the magazine.

Following is an extended quote by John from the article. Since we have Gorre & Daphetid no. 34 in our collection, I pulled it out of its display case to shoot some photos to provide illustration for some of John’s techniques:

John: “All locos don’t get the same amount of weathering. It depends on the service and the time between major repairs. Locos working around mines or cement plants just naturally pick up residue, which road locos do not. Locos working coal mines will be dirtier – even filthy – with coal dust setline on the surface over and above the normal road service grime. Locos around cement plants will be dusted with a base of color from cement dust in the air. Water in our territory requires treatment, so GD Line locos show deposits of boiler compound everywhere steam escapes, such as pops, whistle, cylinders, etc.

“I paint by hand brush, using flat oil paint, and I prefer two thin coats to one heavy one to lessen the chance of obstructing fine detail. Before painting, all boilers [surfaces] are cleaned thoroughly, generally by lightly scrubbing them with weak acid, then rinsed and dried. I never paint a loco dead black. I mix the paint, usually about 70 percent black, 25 percent white, 5 percent red. Proportions vary from loco to loco. The principal thing to remember is to not overdo the weathering so it becomes a caricature. It should always appear to have been done unintentionally over a period of time.”

John continued his thoughts on weathering with a couple of photos and captions:

John: “No. 25 is one of GD’s older locomotives used in branch or mine service. It shows much ore deposit and road grime. The large whitish streak running down from the steam dome is boiler-compound residue from repeated safety and whistle blows. Due to its age and light tractive effort, No. 25 sees only occasional service, but this points up the fact that when a loco is modeled to be aged and weathered, but still in service, none of the essentials should be left off. It must be as carefully modeled as your newest [engine], only grime and rust are increased.”

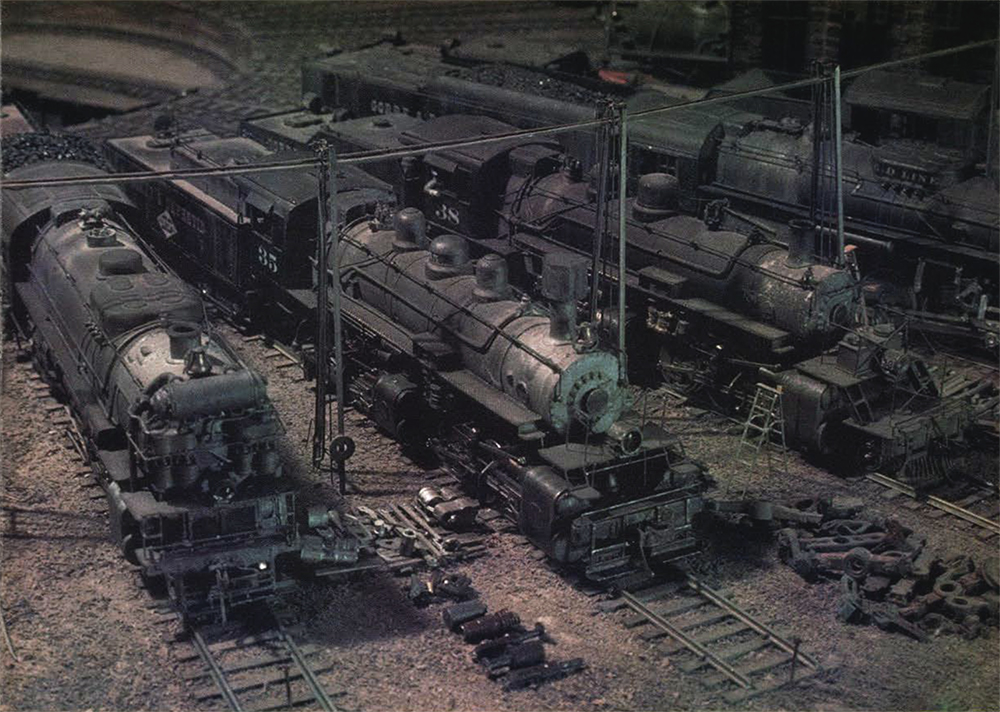

John: “In this scale-pigeon’s-eye view of power on GD’s ready tracks, note that No. 38 is redder than its companions. This is because of heavy service around the mines, where it picks up deposits of ore dust. No. 45 [far left] is in mainline service and No. 35, the 0-6-6-0, is used mostly in helper service. These two do not pick up ore dust but only normal road grime. No. 37 [top] is in for repairs and may be scrapped. Note that age and lack of recent use show in rust coming through the old paint.”

Based upon the information provided by John from the 1964 MR article, we can now look at how he used some of these techniques on No. 34, a 4-10-0, saved from John’s original layout when his house burned. Although the locomotive was in the house at the time of the fire, it was not in the layout room and survived.

In this side view of No. 34, we can see many of the places John used his boiler-compound effect, which are the white deposits on the firebox, whistle area, and cylinders. This locomotive also has a number of red dust marks, denoting likely mine service. As a side note, somewhere along the way, the locomotive lost its bell. The engine was known to not be a reliable runner and was on John’s workbench out of service at the time of his death.

This top view shows more boiler compound around the whistle and pop-valves. It also shows some soot marks around the stack, as well as more reddish dust along the top of the boiler. And on the running boards.

The view of the tender provides a good example of John’s custom mixed light black paint he used on the model before applying the weathering. It also shows the difference between the rust colors John used at the back of the coal bunker by the water fill hatch, and the reddish hue of the ore dust effect he applied to the back of the tender and along its sill. Also note that John hand-lettered his models with white paint. The GD diamond was often just a piece of paper, also hand lettered, applied to the model after the rest of the work was complete.

This close-up view of No. 34’s cab shows a few more of John’s weathering secrets. First, he used thinned paint to do some of the streaking effects, as shown on the side of the tender and the door behind the engineer. He also used a thinned wash of his boiler compound paint on the drive wheels directly below the firebox, and this detail appears on both sides of the model.

An additional point of interest in this view includes the orange paint marks at the bottom of the firebox and on the pipe directly below it. They only appear on this side of the locomotive, and almost look as though they are chipped paint with red primer underneath. Also, if you look carefully, you can see that the No. 34 is painted in a slightly darker black rectangle, indicating that this patch has been repainted once. Perhaps no. 34 was renumbered at some point, or perhaps John didn’t like his first attempt at hand lettering the engine. Note, too, that the upper left corner of the rectangle is missing, along with part of the numeral 3, as though the paint flaked away.

For more information on weathering steam locomotives, check out Detailing and Upgrading Steam Locomotives.

Beautiful weathering, reproduction of photos not so much.