If you’ve read Model Railroader or many of our books and special issues, you’ve probably seen references to timetable-and-train-order operation, or TTTO for short. Employee timetables (ETT) that governed TTTO operation listed station names, mileposts, train numbers and classes, departure and arrival times, and operating instructions, among other items, to govern train movements. So why did railroads use train orders? The dispatcher-issued messages were used to supersede and supplement the timetable.

Though train order use is extremely rare today, Direct Traffic Control, Form D control, and Track Warrant Control still use instructions (orders). However, instead of relying on operators to relay the messages, the instructions are transmitted directly to crews via radio.

How train orders worked

Dispatchers sent train orders to operators at a station or tower, and on rare exceptions directly to the train crew. There were two primary reasons to use them. The first was to supersede the timetable. If scheduled trains were falling behind schedule, train orders could be used to change the movements of other trains on the line.

Train orders could also be used to supplement the timetable. Examples include annulling scheduled trains, running extras, or updating operating conditions (slow orders, soft track, and noting locations of occupied camp cars, for example).

Two types of train orders

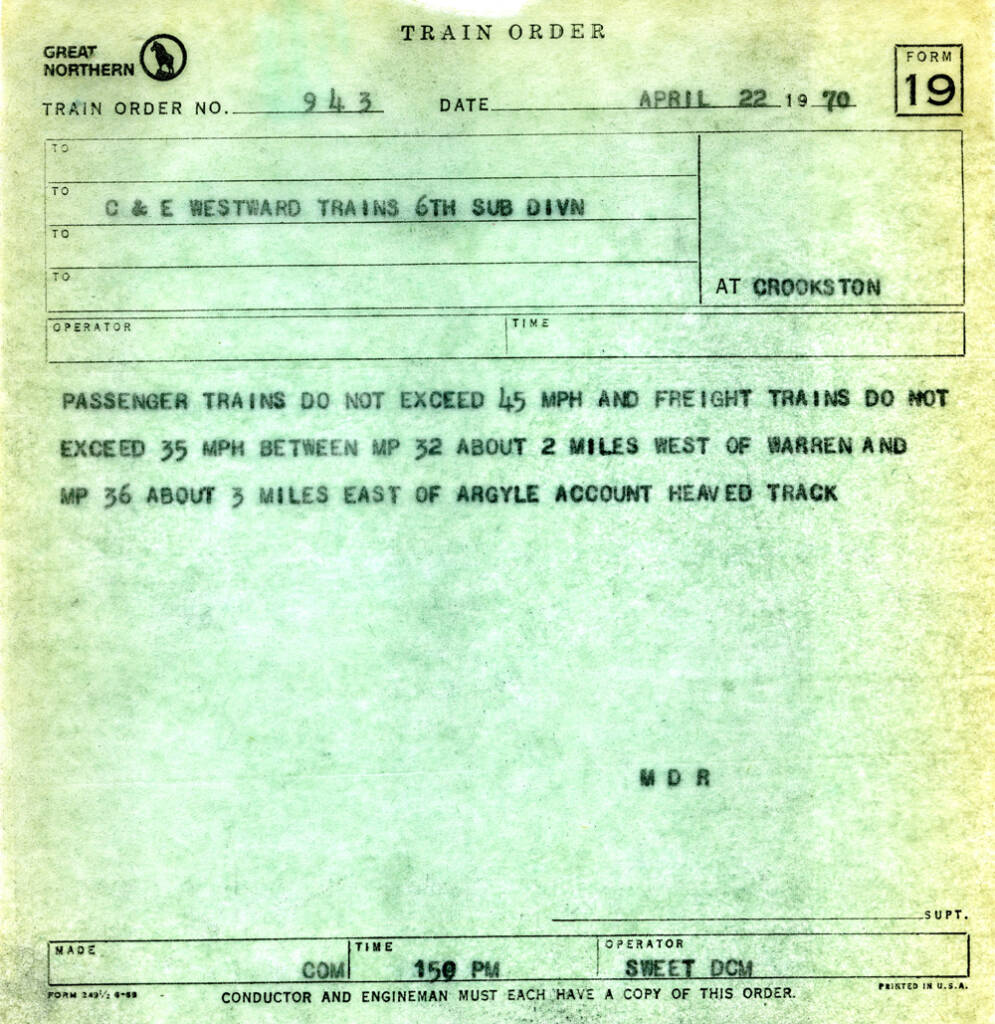

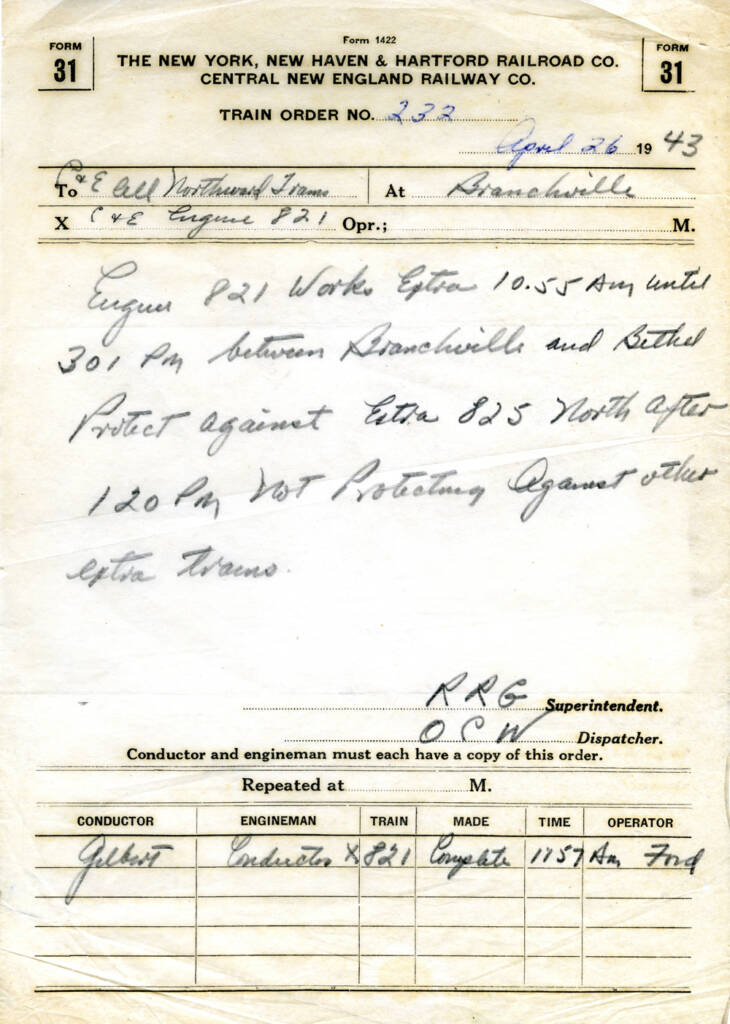

There were two types of train orders, Form 31 and Form 19. Both were printed on tissue paper, earning them the nicknames “flimsies” and “tissues” by railroad employees.

Form 31 train orders, which weren’t used by all railroads and largely fell out of fashion by the 1960s, required trains to stop. The book “19 East, Copy Three” by David Sprau and Steve King (Operations Special Interest Group, 2013) states, “A train order form ‘31’ required a conductor’s signature at delivery to confirm the order had been received, read, and understood. As trains got longer and heavier, stopping to sign a ‘31’ order caused operating problems. So the railroads introduced the train order form ‘19’ for those less-critical train order situations.”

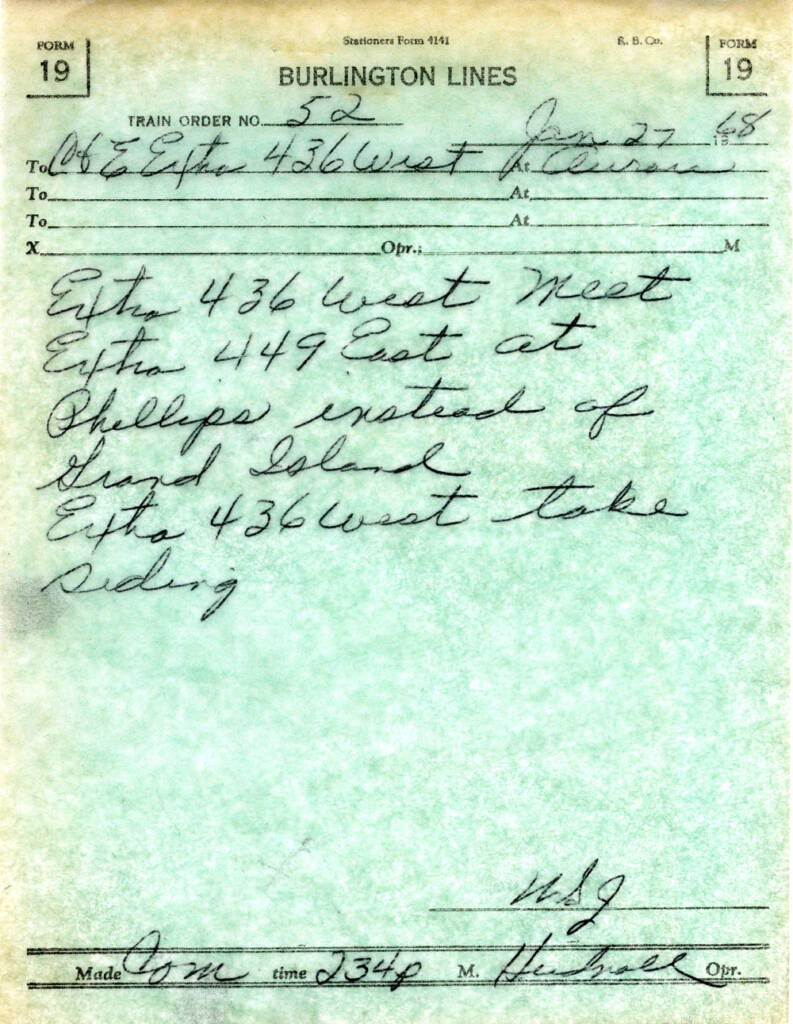

Form 19 orders could be issued to trains in motion, a scene often documented by railroad photographers. In Bruce A. Chubb’s 1977 Kalmbach book How to Operate Your Model Railroad, he wrote, “Form 19s could be delivered to a train without stopping it because the train’s safety would not be jeopardized if the train proceeded on before the crew had a chance to read the order.”

Styles for each situation

“Wait a minute! You just said there were two types of train orders, Forms 31 and 19. Now you’re showing me a list of more than 20 additional forms. What gives?” Below are the alpha codes that outlined how train orders should be written for specific situations. I compiled the list below from the two books listed in the previous section. Prototype-specific forms can be found in railroad rulebooks.

For example, I have a copy of Burlington Northern’s Train Dispatcher’s Manual from December 1979 which lists the various train order forms the railroad was using at the time. In addition, it provides details on each form and a sample. For example, under Form S-A, it says, “When train order meet is issued between opposing trains the train order must in all cases designate the train which is to take siding. The “take siding” instruction must appear at the beginning of the order. Example: No. 2 take siding meet No. 1 at __________.”

Why were there so many prescribed train-order forms? For safety. All employees (dispatchers, train crews, maintenance-of-way gangs, etc.) were trained in what the different forms meant and how to act on them. Interestingly, the BN manual noted that dispatchers must “Adhere to prescribed forms were applicable. If prescribed forms do not suffice, an improvised order shall be brief and clear and not in contradiction to the prescribed forms.”

- Form S-A: Fixing meeting points for opposing trains

- Form B: Directing a train to pass or run ahead of another train

- Form S-C: Giving right over an opposing train

- Form E: Time orders

- Form F: For sections

- Form G: Extra trains

- Form H: Work extra

- Form J: Hold order

- Form K: Annulling a schedule or section

- Form L: Annulling an order

- Form M: Annulling part of an order

- Form P (or S-P): Superseding an order or part of an order

- Form R: Providing for movement against the current of traffic

- Form S: Providing for use of a section of double or more tracks as single track

- Form T: New timetable notice

- Form U: Advance authority to proceed from ABS stop signal

- Form V: Check of trains

- Form W: Clearance or register requirements

- Form X: Slow order

- Form Y: Maintenance-of-way conditional stop

- Form Z: Relief of flag protection

On your layout

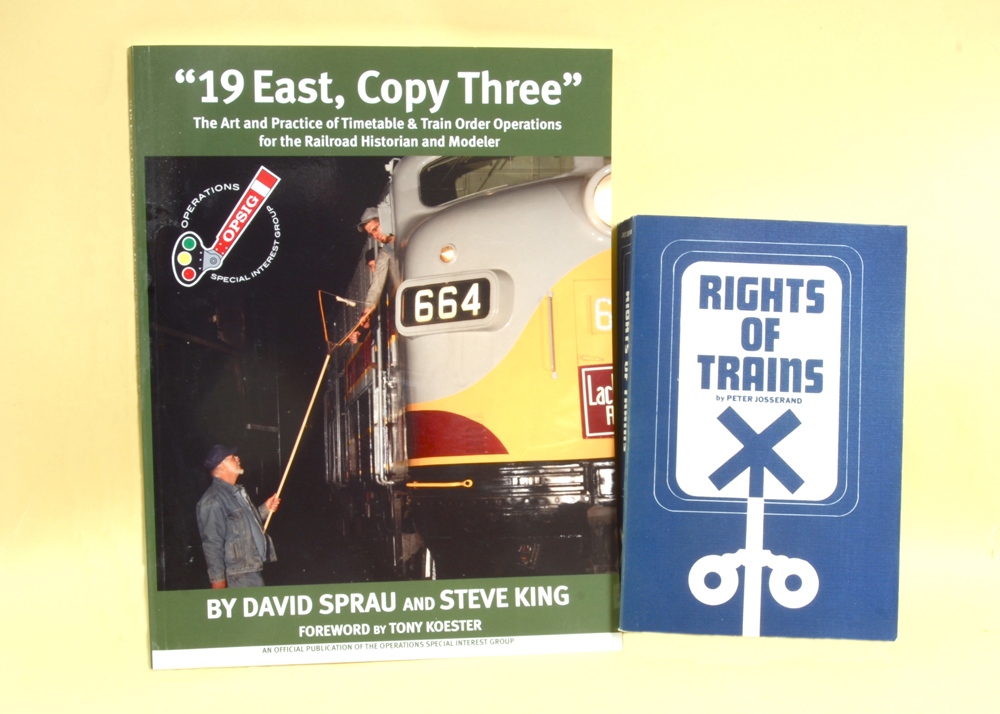

Timetable-and-train-order operation isn’t something you’re going to learn overnight. Fortunately, there are a variety of resources out there to help you. The Operations Special Interest Group is a great starting point. The group’s book “19 East, Copy Three” is a valuable book as it provides historical information on TTTO operations and ideas on how to adapt it to a model railroad.

Peter Josserand’s book Rights of Trains, now in its 5th edition, covers both TTTO operations and other methods of train dispatching. Many model railroaders who run their layouts with TTTO recommend this publication.

Model Railroader Contributing Editor Tony Koester’s book Realistic Model Railroad Operation: Second Edition (Kalmbach Books, 2013) devotes a chapter to timetable-and-train-order operations. Though the book is out of print, used copies can be found at model railroad swap meets, online auction websites, and used book dealers.

Jerry Dziedzic’s monthly column “On Operation” in MR explores a variety of operating topics, including TTTO. In fact, his January 2024 column was “Delivering train orders.”

Micro-Mark has paperwork for getting started in TTTO operations. The company offers Form 19, Form 31, and Clearance Form A pads.

I recently began collecting used train order forms from my hometown and have found them valuable for a variety of reasons. First, I’m able to get a better idea of how the Burlington Northern operated in the early 1970s. Second, the documents let me study the various alpha code forms used by the railroad. I’ve been able to see how meets, slow orders, and other situations were handled. In addition, the Form 19s often indicate the road number of the lead locomotive, giving me an idea of what units were used in the area at the time.

Even if you don’t plan on using TTTO operations on your own layout, it’s good to have an idea of how it works, especially if you plan on attending operating sessions. There are plenty of resources out there, and plenty of people to learn from. Don’t be afraid to ask questions!

I’d like to thank Jerry Dziedzic for his assistance with this article.