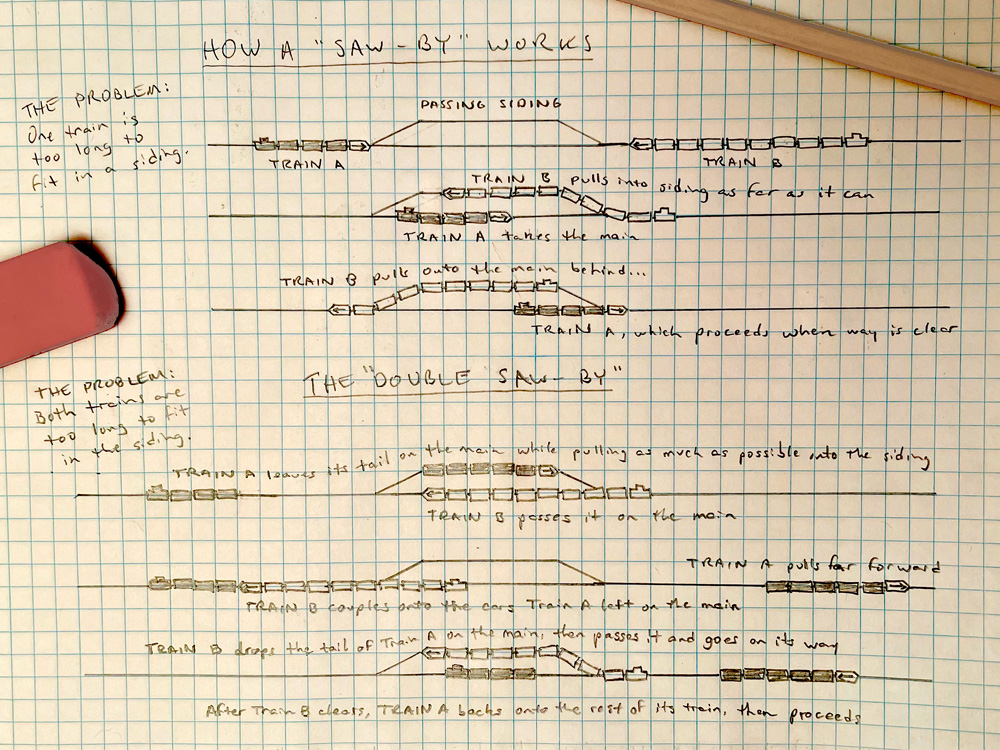

When two trains running in opposite directions on a single-track main have to pass each other, the dispatcher will schedule them to meet at a passing siding. But what happens when one or both of those trains is too long to fit into the siding? Engineers coped with this situation with a maneuver called a “saw-by.”

Since the saw-by requires both trains to come to a stop, and time is money on the railroads, dispatchers tried to avoid this situation by scheduling the meet for a location with a longer siding, splitting one or both trains into multiple sections, laying over part of the train on a nearby spur, or other tricks. But complicated maneuvers like this can add what modelers like to call “operating interest.” Challenges are fun! After all, it was modelers who invented the switching puzzle. You might want to schedule a saw-by meet at your next operating session, if only to watch the engineers sweat.

Here’s how a saw-by works. The first example is fairly simple and occurs when only one of the trains is too long for the siding. The longer train (Train B in our diagram) pulls as far as possible into the passing siding and waits for Train A. When it arrives, Train A takes the main, then its brakeman lines the turnout behind it for the passing siding. Train B exits the passing siding onto the main behind Train A, returns both turnouts to normal, then proceeds on its way. With the track ahead now clear, Train A then proceeds.

This assumes the longer train arrives first. If the first train to arrive at the meeting point fits into the siding, it doesn’t matter how long the other train is.

The Double Saw-By

Now for a trickier puzzle. What happens if neither train can fit into the siding? The solution is the double saw-by, which involves splitting one of the trains into two chunks.

For the double saw-by, Train A would leave part of its train behind on the main (protected by a flagman, no doubt) and pull as much as will fit completely onto the passing siding. Train B then passes it on the main, letting the front end of Train A enter the main behind it and pull several train lengths forward.

Train B then couples onto the remainder of Train A that was left on the main and backs up. It drops those cars onto the main alongside the passing siding, then uses the siding to run around those cars and go on its way. Finally, Train A backs up, couples to the rest of its train, and resumes its own journey.

“But what happens if Train A is so long that the back half it leaves on the main is also too long for the siding?” I can hear you ask. Well, although I’ve never heard it called a triple saw-by, such a maneuver would be possible, with Train A backing up to pick up multiple chunks of its back end as Train B drops them on the siding. I’d imagine that most dispatchers would rather pursue any number of other solutions before scheduling a maneuver like this.

If you’re looking to add some challenge to your next operating session, try putting a few too many cars on the trains scheduled to meet on a short siding. Unlike on the prototype, your engineers will probably have a great time figuring out how a saw-by works.

I remember learning what a saw-by is while riding on Amtrak. If done right, the shorter passenger train only needs to slow down. However, we had to stop because they had trouble throwing the switch behind our train. Finally, the freight locomotive had to throw the switch by pulling onto it and forcing the points to move. Our conductor explained to me what was happening and told me it was called a saw-by.

The key question to go with this is “how long does a double saw by take?” It would have to be hours because we’re talking miles back and forth at slow speeds, not to mention all the walking the crew would have to do. Wouldn’t this create a traffic jam all up and down the line, esp in TT&TO days?