Most modelers build their first layout as a loop that lets them sit and railfan the passing train. Even if freight sidings and spurs are added to the loop, it’s still easy to run the train without doing any switching or having to turn the locomotive. However, once the train has completed a dozen laps or so, most people become bored.

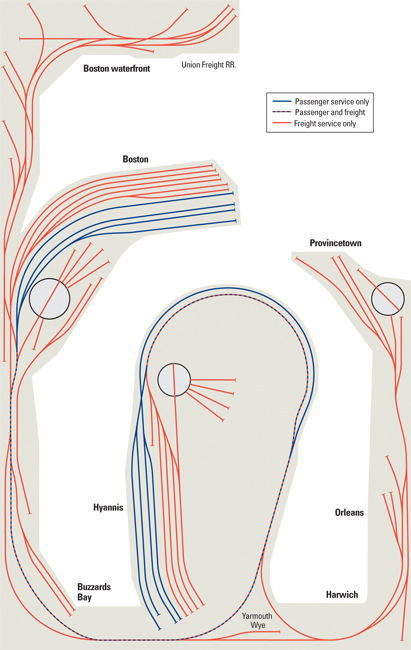

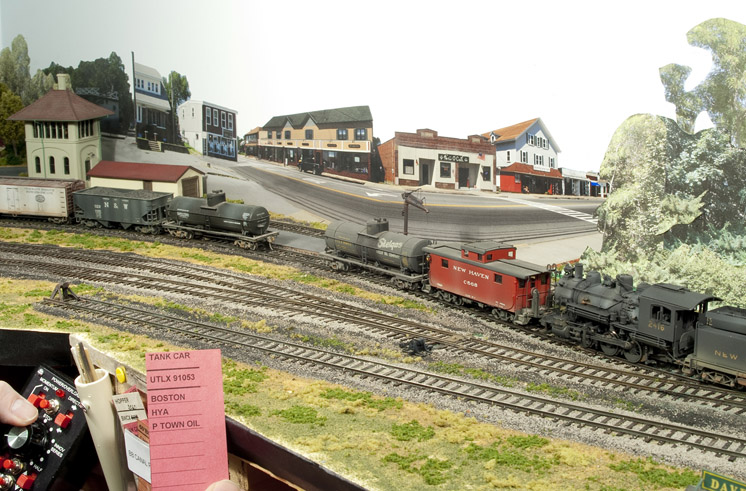

In contrast, prototype railroads operate on a point-to-point basis and are focused on their primary business – moving freight. Some passenger service may also run on part of the line, but these trains seldom produce a profit due to their operating costs. I model the New Haven RR on Cape Cod, Mass., in 1948. My article on the HO scale layout, “New Haven’s Cape Cod branch,” and its track plan was published in the October 2006 Model Railroader magazine.

The railroad begins on the Boston waterfront, where freight cars are picked up from the shipping docks and warehouses by the Union Freight RR and transferred to the New Haven’s South Boston Yard. These cars are then switched into trains for Cape Cod.

The road freight trains head south to Buzzards Bay, pass over the Cape Cod Canal Bridge, and head into the Yarmouth wye. The northwest leg of the wye curves toward Hyannis yard, where trains

either terminate or are split up into short peddler freights. Peddlers bound for Provincetown (at the tip of the cape) leave via the wye’s northeast leg. Some freights may travel straight through the wye, traveling directly from Boston out to Provincetown. There’s also passenger traffic on the line, but it only runs from South Station (Boston) to Hyannis. Figure 1 shows the freight and passenger traffic patterns I’ve incorporated into the railroad.

I initially used two kinds of paperwork to achieve realistic operation: a car card system for the freight car forwarding, and an event, or train sequence, list that directed the passenger trains.

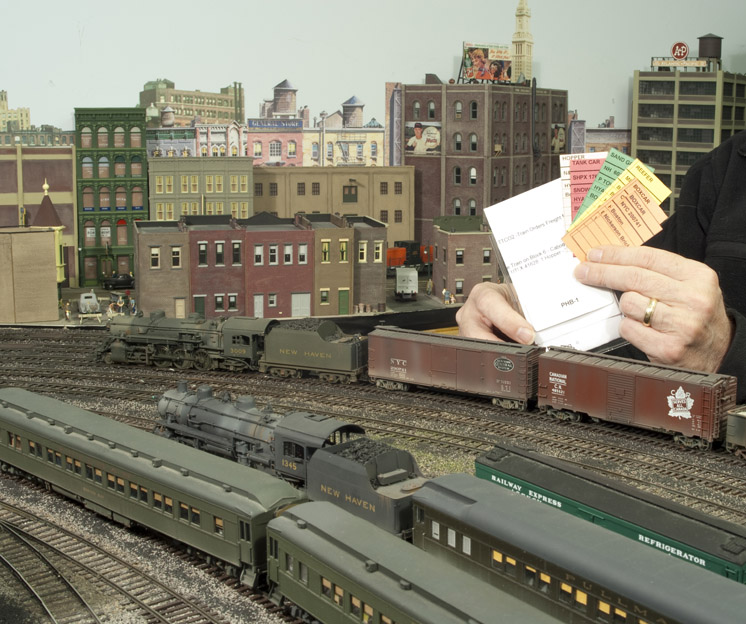

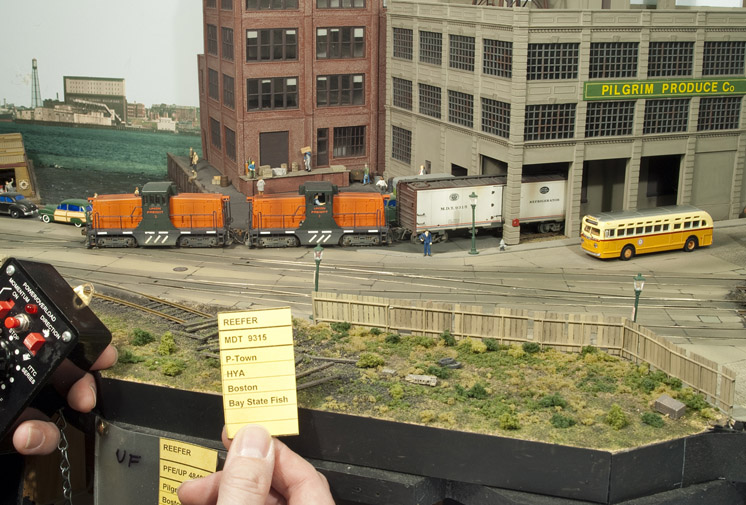

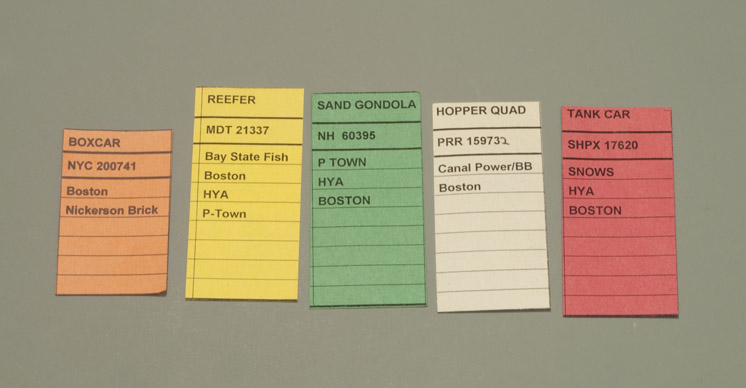

Let’s review how the car waybill system works. Inbound loads from connecting railroads arrive at the main yard for sorting and delivery to customers along the line. Outbound cars (loads or empties) are picked up from the on-line customers, fig. 2, and taken back to the yard where they’re switched into blocks (groups) of cars for connecting railroads. Each freight car has a car card, or “waybill,” which lists its basic information: the owner’s initials, car number, destination, and contents.

The waybills for cars spotted at the local industries are placed in small plastic pouches filed at each switching location, as seen in fig. 4. When a car is in transit, its waybill is placed in a pouch that travels with the train conductor so the crew knows which cars are to be picked up or dropped off at each stop. Each pouch is labeled with the symbol of its train.

Passenger service

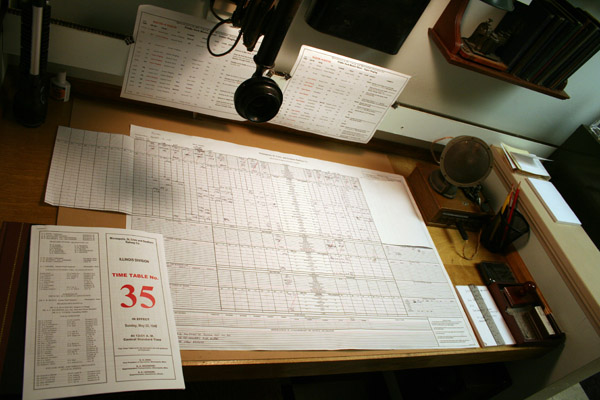

My passenger trains are identified by their routes and stops. Since both freight and passenger trains share the same track, I use a master sequence list to coordinate all of the train movements on the railroad.

Some model railroads use fast clocks (special clocks that run at a higher-than-normal speed to enhance this time/ distance effect). On my small railroad, I prefer to let the normal sequence of events drive my master list.

Sequence list “schedules”

My operating sessions last from 1½ to 2 hours, and we have six operators. We use DC cab control with walkaround throttles, but the operators remain at their assigned locations and pass the trains along to simulate the New Haven’s 1948 style of manual block operation.

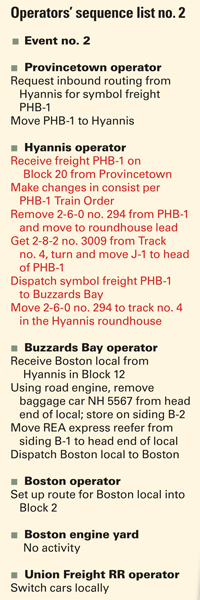

The sequence list does three jobs:

• It divides the operating session into six approximately equal periods that cover a sequence of events.

• It shows what each operator should accomplish during each event, as shown in fig. 5.

• It recommends routes for each train to avoid the problem of having two trains occupying the same DC electrical block at the same time.

This sequence list isn’t designed to handle car orders, which are half the fun of the operating session, and the car order system isn’t equipped to prevent two trains from entering the same block.

Combining the functions

Combining both functions led me to this hybrid sequence list that includes authorizations for train movements and car switching instructions. This system is an adaptation of the original operating system I explained in my earlier article “Sequence ‘timetables’ made easy” in the October 2002 Model Railroader.

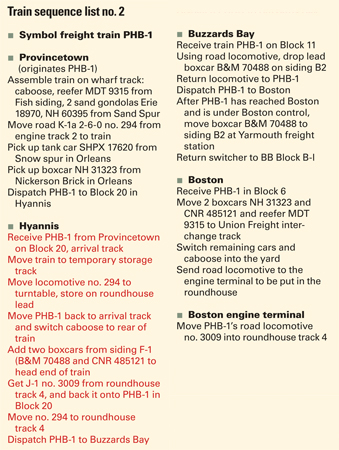

My operators and I have already developed two hybrid sequence lists and we’re working on a third. Figure 5 shows event no. 2 in our second list. This list is organized around stationary operators running a particular position and then handing the trains off much like prototype manual block operators. I have chosen the Hyannis Yard operator’s job (highlighted in red) as an example.

Hyannis is a stub-ended terminal with freight, passenger, and locomotive facilities. It can be reached from outer Cape Cod (Provincetown) by freight trains arriving through the northeast leg of the Yarmouth Wye. Similarly, passenger and freight trains from off-Cape can be routed into Hyannis through the northwest leg of the wye.

From the Hyannis operator’s perspective event no. 2 covers symbol freight PHB-1’s (Provincetown-Hyannis-Boston) arrival from Provincetown, picking up cars, changing engines, and then heading for Boston. The car handling instructions on the hybrid time- table come into play as the freight cars are switched in the Hyannis yard.

In fig. 6, the hybrid train list for PHB-1 has been highlighted in red so the Hyannis operator can easily see the changes he must make in this train as well as the switching moves that he has to handle during the train’s Hyannis stop. Finally, he needs to locate the waybill for each of the cars involved and transfer them to either the yard file pouches or PHB-1’s train pouch. Once the through train has left for Buzzards Bay, the yard crew gathers the setouts and delivers them to the customers’ docks or to the Hyannis freight house.

At the end of each event, we take a short break to see how everyone is doing and let anyone who needs a little more time catch up. If all is well, we continue on to event no. 3, and so on.

At this point, my entire operating crew seems to enjoy working with this new hybrid train sequence list system. By combining functions, we can still use the car waybills and enjoy a new operating experience.

Nice! this was a great article. On my layout I use the waybill operating system, and I really enjoy running trains with it.

First, let me say how much I enjoyed this article. For one thing, John Pryke is an excellent New Haven RR modeler. As a fellow NH modeler it is very impressive how in the limited space he has simulated some of the operations on what was the former Old Colony RR before it was merged into the NY, NH & H. It was interesting because he approaches from a entirely different operational perspective how to operate a good chunk of the track John Armstrong captured in his track plan on the Old Colony Lines in 1960. It seemed to me that Armstrong emphasized passenger operation and made freight a minor part of the operations. John Armstrong also placed heavy emphasis on the timetable to regulate train movement. Of course Armstrong was proposing a much larger layout.

Pryke also makes the point without switching and attempting duplicate prototype operation, train running is pretty boring. This is a point on which I totally agree.

As a teenager I was crew member on a rather large private layout. Everybody except the occasional visitors want the yard assignments and switching jobs. It was great fun and a mental challenge to get trains classified and moved within the timetable times.

One interesting aspect to me is that Pryke, Armstrong, the Pelham Model RR Club in the 1930’s, and a track plan on the New Haven between Grand Central Station and Boston (“To Boston on Time”) which appeared in Railroad Model Craftsman in the 1970’s, all recommended block tower control as being the most suitable control scheme for portraying the high density operations, but short haul nature of the New Haven RR.

Finally, it was gratifying to seeing a full article on the operations on an actual model railroad.