THE PROTOTYPE, FREELANCED

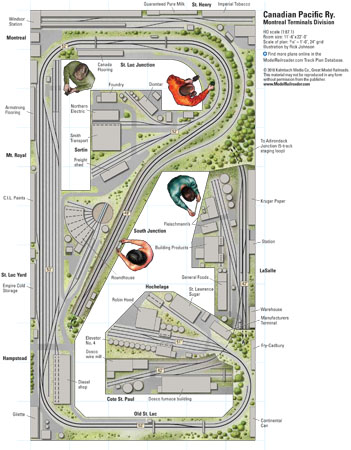

The ongoing challenge has been to build a convincing representation of the Montreal Terminals, a modeling subject worthy of a club-size layout, in a 12 x 22- foot room. There were five major yards, the CPR’s headquarters in Windsor Station, Angus Shops, and 350 sidings.

My layout is “proto-freelanced.” Space limitations made it impossible to accurately re-create even a few actual locations,track arrangements, or industries, but they served as nspirations.

Likewise, an operating session includes a fraction of the real number of trains seen by the prototype. On a typical day in 1968, 60 intercity passenger and commuter trains, 30 freights, 20 transfers, and numerous switch jobs appeared on the division’s 47 miles of main line. My operating sessions have eight passenger trains, eight freights, five transfers, and five switch jobs. I’ve created an illusion of the busy division by running a ufficient number of trains, all having prototypical consists and operating in a realistic manner, through scenes with easily identified CPR railway facilities and industries. Mine is a mid-size layout where mainline freights bring cars to a central yard, which dispatches transfers and switch jobs to deliver them

KEY DESIGN ELEMENTS

I tried to observe well-accepted and practical layout design principles, but ultimately had to make some compromises. I resigned myself to having two duck-unders and narrow aisles, and haven’t looked back. The result is a layout that fills the room, and some would say overfills it. But this is the appearance I want – a congested, urban railway.

There were a few key elements I absolutely had to include in my out-and-back design. St. Luc Yard is the main yard. Its five double-ended classification trackshave a capacity of 67 cars. There’s an arrival/departure track of 30 car lengths and a pull-down track (switch lead) 20 cars long. The classification tracks can do double duty as arrival and departure tracks. There’s also a van siding (CPR for a caboose track) and two storage tracks. All road freights and transfer jobs originate at and return to this yard.

The St. Luc service area has a two-track diesel shop, a six-track roundhouse, and two fuel and sand tracks. The six industrial areas – Mount Royal, Hochelaga, Sortin, LaSalle, Cote St. Paul, and St. Henry – have a total of 16 online customers, plus a CPR freight shed, with a total of 51 car spots.

Windsor Station is a three-track, stub-ended passenger terminal. I wanted the Adirondack Subdivision main line to be double-tracked from St. Luc Yard to staging. The hidden staging area includes five double-ended tracks arranged as a reversing loop, with capacities ranging from 16 to 30 cars.

I spent my working life in heavy industry, and am interested in industrial archeology. So my online industries must be accurate in terms of building and equipment design. I’ve devoted considerable time to studying Canadian fire insurance maps, high-resolution aerial photographs, and historical images of the areas and buildings I’ve modeled.

Though space limitations precluded scratchbuilding exact replicas, my industries are based on signature buildings that can be readily identified. For example, in nearly every photograph at the real Hochelaga Yard, the white, six-story Manufacturers Terminal Co. building is in the background, so I modeled it closely. My Guaranteed Pure Milk dairy next to Windsor Station has the prototype’s characteristic white, milkbottle- shaped water tower. My model of the Dominion Steel Co.’s St. Patrick Works replicates the building’s construction type, scrap piles with travelling cranes, and rolls of wire everywhere.

QUALITY CONSTRUCTION

In the first year and a half I spent planning the layout, I hand drew numerous track plans until I finally had one I thought would work. I made multiple photocopies of my final draft design and marked the position of every train at the start of an operating session. Each time a train moved to a different location, they would all be marked on another copy of the track plan. Determining where every train would be at any time and in what sequence they would operate told me how many trains the layout could support, as well as the number and length of station, yard, and staging tracks those trains would require.

Setting and maintaining high standards of construction went a long way in facilitating prototype operations on the layout. I spent considerable time ensuring the benchwork and tracks were built to very high standards. I didn’t cut corners, as there is nothing more frustrating and unrealistic than frequent derailments and stalling at slow speeds. Derailments are few on my layout and never the result of poor construction, but rather operator error.

Trains are run by direct-current (DC) block control. Every section of track has drops to 16 gauge feeders. All connections use terminal strips. Four GML Enterprises walkaround memory throttles provide excellent control.

The layout runs flawlessly, and I’ve made only minor repairs to three turnouts in 20 years. All I do is vacuum the

layout and clean the track and locomotive wheels once a year. I have no plans to convert to Digital Command Control (DCC) and sound, as I can’t justify the time and expense. I am usually a lone wolf operator or with one or two others, and the DC control system is more than satisfactory for my needs.

REALISTIC OPERATIONS

I chose the time frame of late summer 1968, as this was just before the CP adopted its Multimark rebranding, which I never really liked. Though the track arrangements are freelanced, the operations follow the prototype as closely as possible. I’ve replicated my favorite trains of the era. There are four passenger trains: the Atlantic Limited to St. John, New Brunswick; the Delaware & Hudson’s overnight Montreal Limited and daytime Laurentian to New York, powered by ex-Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Alco PAs; and one CP Dayliner local.

There are four mainline freights: CP No. 908 to Saint John; CP No. 904 to Wells River, Vt.; Napierville Junction No. 105 from Rouses Point, N.Y.; and Penn Central VM11 from Syracuse, N.Y. Five transfers and two switch jobs serve the industrial areas. There are, in addition, three yard switcher jobs – two in St.Luc Yard and one at Windsor Station.

THE OPERATING SCHEME

There are different schemes for prototype operations, depending on the era being modeled. In 1968 the Montreal Terminals was run by timetable and train order (TTTO).

I started to develop the detailed operating scheme when all the track was fully functional in the late 1990s. I studied the CPR employee timetables and the Schedule of Fast Freight Trains from the era to understand how the division operated.I read the CPR General Operating Instructions and the Uniform Code of Operating Rules (UCOR) to understand how the CPR ran trains. I pored over my hundreds of slides and negatives to create

realistic consists. While doing this, I had the radio scanner on in the background listening to how the real Montreal Terminals was operated by the professionals. What an education that was!

The main consideration for the freight trains is that the CPR didn’t move loaded cars between online customers within the Montreal Terminals. This was both because of the very short distances and the fact that these industries produced many more empties than loads. Therefore, cars come from and go to places off the layout, represented by staging.

An operating session begins with CPR No. 904 and the five transfers ready to depart St. Luc Yard, having been made up in the previous session. Train 904 heads to staging and the transfers go to the industrial areas. The transfers switch Mount Royal, Sortin, and St. Henry, while the industries at LaSalle, Cote St. Paul, and Hochelaga are served by switcher jobs assigned to those yards.

While the transfers and switch jobs are working, Napierville Junction No. 105 arrives at St. Luc Yard from staging, with cars for interchange to outbound freights later in the session and the next session’s transfers. As the transfers return to St. Luc, the yard crew makes up the two outbound freights (CPR No. 908 and Penn Central MV12) that depart late in the session, as well as the next session’s CPR No. 904.

Later on, three more freights (CPR No. 915, CPR No. 949 and PC VM11) arrive from staging with more online and interchange cars for the next session. The session concludes with the St. Luc Yard switch crew making up the next session’s CPR No. 904 and five transfers.

While all this is going on, eight passenger trains operate between Windsor Station and staging.

The mainline freights require about 80 cars. The transfers provide 50 of those cars, and direct interchange from the Napierville Junction and Penn Central freights add the other 30.

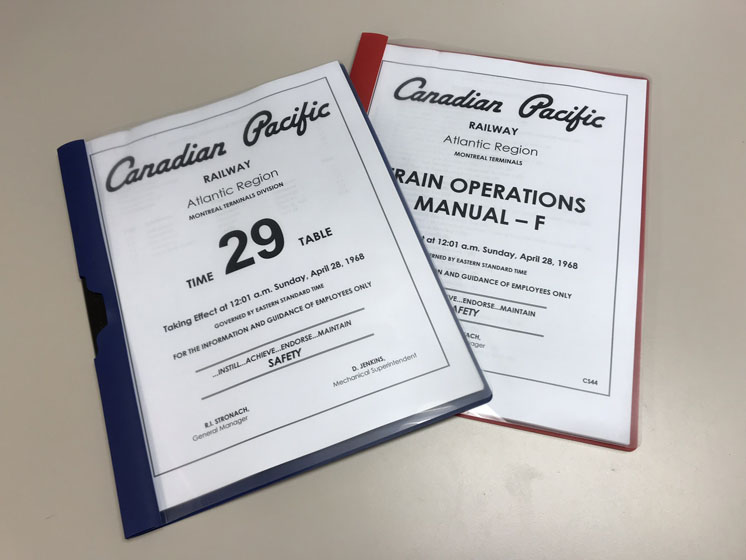

I’ve created an employee timetable to govern operations on my railroad, copying the style and format of the actual CPR Timetable No. 29, April 28th, 1968. It includes train schedules, subdivision footnotes, special instructions, train operating procedures, locomotive tonnage ratings, track diagrams, and the Car Control Manual. I wrote actual footnotes for the layout’s trackage.

For example, Sortin has a 16″ radius curve, to which two footnotes apply:

“J. Cars 50 feet or longer and equipped with cushion underframe draft gear must not be coupled together but must be separated from each other by a 40 foot or shorter car with standard draft gear due to the sharp curves. Extreme caution must be exercised when negotiating Sortin trackage due to the sharp curves.”

“K. When pushing cars after uncoupling, the bodies of the couplers must be properly aligned in the delayed action position so as to prevent derailments on sharp curves due to lateral forces on the outside of the couplers if misaligned.”

The timetable has been reissued seven times as I fine-tune my operations with input from two retired CPR dispatchers.

Recently, I added the CPR Car Control Manual, which provides crews with details of how to switch each online customer. The tonnage ratings of diesel units are provided, and operators have to do the math when making up trains to determine the consist needed to haul a train up the ruling 2 percent grade between LaSalle and St. Luc Junction (60 tons for a 40-foot car and 70 tons for a 50-footer).

USING SWITCH LISTS

I’m more interested in running trains than being the yard clerk or conductor doing lots of paperwork. I have no need for a car-card system, as cars don’t move between industries on the layout. Therefore, car forwarding is accomplished with switch lists. The twist is that I don’t have to make them before an operating session. Specific cars are assigned to each industry, as in the following example.

Building Products in LaSalle ships roofing shingles in 40-foot boxcars. Operating session A begins with three cars on the layout dedicated to this industry: CP 226259 is loaded at the plant, waiting to be picked up by Transfer 212; CP 252512 is in St. Luc Yard in the consist for Transfer 212, which will set it out; and CP 221755, in Train No. 949 in staging, will return to St. Luc Yard as an empty, destined for Transfer 212 in operating session B. The cycle of car positions repeats every three operating sessions. Interestingly, CPR had 40-foot boxcars assigned to captive service for the real Building Products, so there is a prototype for everything!

Cars interchanged at St. Luc Yard directly between inbound and outbound freights cycle every two sessions. Therefore, with some cars cycling every two sessions and others every three sessions, it takes six to get all cars back to where they started.

Each manual also contains a switch list for St. Luc Yard, which provides consists of all inbound trains and how the cars are to be blocked for the outbound road freights and transfers.

TRAIN ORDERS AND SIGNALING

Every session has an Operations Manual in which each train has one or two pages of nstructions. The paperwork is a combination of a clearance,train orders, operating instructions, and switch list. I don’t need train orders, as scheduled trains and extras (the occasionalwork train or Sperry test car) simply need a clearance to leave St. Luc Yard or Windsor Station, since the division is double-track, directional running with automatic block signals (ABS).

The entire Montreal Terminals is within yard limits. So on main tracks, all trains run at track speed by signal indication and have to get out of the way of first-class trains. Everywhere else, movements are at restricted speed. Where there is a need to wait for another train, the “train order” is included in the operating instruction. For example: At 6:50 a.m. run engine light from St. Luc to South Junction. Wait until Transfer 210, Engine ___ and Train No. 41, Engine ___ have arrived. Run to Montreal. Pick up train on Windsor Station Track No. 3. Run to Adirondack Junction Track No. 1.

OPERATING

Running 21 trains per operating session means there are a number of meets. I most often operate alone and have multiple trains on the road at one time. There’s no fast clock, and the trains follow the sequence or schedules in the employee timetable.

I know, for example, when operating Transfer 212 that I have to get clear of the Northward Track at LaSalle to let the Atlantic Limited go by. At this point in the session I’ll stop operating Transfer 212, run the Atlantic Limited to Windsor Station, then resume switching.

There is virtually no work required to prepare for an operating session, and it can be stopped and restarted at any time. The staging yard is a reversing loop design, so there’s no fiddle work required to re-stage trains.

At the beginning of each session I act as the diesel shop planner and complete the power lineup, assigning units to all trains. I change some of the power off the layout at the end of each session because I have so many interesting diesels I like to operate.

The diesel shop hostler is a job in itself. There’s a lot of power moving around. Arriving power first goes to the

fuel and sanding area, then to the diesel shop for running repairs or the roundhouse, and finally to the ready track.

I enjoy switching, and the layout provides lots of opportunity. The St. Luc Yard switcher classifies 130 cars per operating session. The transfers and LaSalle and Hochelaga switchers pull and set out 100 cars.

My operating system isn’t as prototypical as some, but it works well and isn’t complicated. The learning curve for guest operators is short. I give them an employee timetable before a session to familiarize them with the layout and trains. Upon arrival I take them for a tour of the layout, explain the controls, and give them the operating instructions for the trains they will run.

What lies ahead for the railroad? The layout is complete, but there remains a lot to be done. Some of the scenery is 20 years old, so it’s being renewed with Scenic Express SuperTrees, static grass, and other new materials. I’m adding another level of super detailing across the layout, one scene at a time. I’m also replacing many older cars as new and better ones become available.

There’s never been a better time to model the CP, as high quality locomotives and cars, true to Canadian prototypes, are now readily available. When I started, Canadian prototype modeling could only be done with brass, which ran poorly and was expensive. I’ve recently embarked on a campaign to weather my 250 cars and 50 locomotives.

My greatest satisfaction comes from operating the layout. I’m constantly challenging myself to operate in a more prototypical manner – running at restricted speed except on the main, stopping to let the brakeman off to line turnouts, pumping the air, doing brake tests, stopping to flag crossings, observing the Uniform Code of Operating Rules within interlocking limits, following labor agreements when yarding trains, and performing

running inspections.

In the last few years after joining the Operations Special Interest Group (OPSIG) and participating in the Yahoo groups Proto Layouts and Railway Ops – Industrial, I’ve become even more focused on replicating prototype operations. I continue to research operations of the Montreal Terminals. I recently received CPR’s maps and lists of every private siding and yard in the terminals for my era, which prompted me to change some industry names and the cars needed. I regularly call my retired dispatcher friend for his advice.

Despite the compromises I’ve made, after 15 years, my Montreal Terminals Division continues to captivate me. I haven’t grown tired of it, and in fact, being retired has given me more time to detail scenery, weather motive power and rolling stock, and best of all, operate the layout as often as I want.

NAME: CPR Montreal Terminals Division

DESIGNER: Ian Stronach

SCALE: HO (1:87.1)

SIZE: 11′-6″ x 22′-0″

PROTOTYPE: Canadian Pacific Ry., Montreal Terminals Division

LOCALE: Montreal

ERA: September 1968

STYLE: around the walls

MAINLINE RUN: 72 feet

MINIMUM RADIUS: 30″ (main), 16″ (spur)

MINIMUM TURNOUT: no. 6 (main), no. 5 (yards)

MAXIMUM GRADE: 2 1⁄2 percent

BENCHWORK: L-girder

HEIGHT: 45″ to 52″

ROADBED: cork on plywood

TRACK: Walthers code 83, Peco code 100 (staging)

SCENERY: plaster gauze on cardboard

BACKDROP: tempered hardboard

CONTROL: GML walk-around direct current

It would have been nice if the real St. Luc Yard was only five tracks when I first had to go there. The real maze of tracks, plus badly outdated maps didn’t help. Individual yard tracks were marked, but the numerous lead tracks to get to them were not. Then we started running D&H trains into Taschereau also – more to learn. I eventually learned how to negotiate it all, but glad to be retired.

Excellent modelling and a wonderful story about CP’s very busy Montreal terminal operations. I saw your reference to No. 949. I used to load box cars at the CP Shed in Brockville, Ontario. The cars were destined for various locations in western Canada, getting there via CP’s Brockville wayfreight (4th Class Train No. 60 during Mr. Stronach’s era) to Smiths Falls, Ontario and then via 949 which lited them along with other freight as well as doing a crew change.