On our layouts, ballast is strictly a scenic element. We use the material, whether it’s crushed real rocks, dyed walnut shells, or other material, to simulate the rocks used on full-size railroads. But prototype ballast is far from cosmetic. Among the uses for ballast on the prototype are to prevent track from shifting up and down, sideways, and lengthwise; evenly transfer weight from the rails and ties to the subroadbed; and facilitate drainage.

Types of ballast

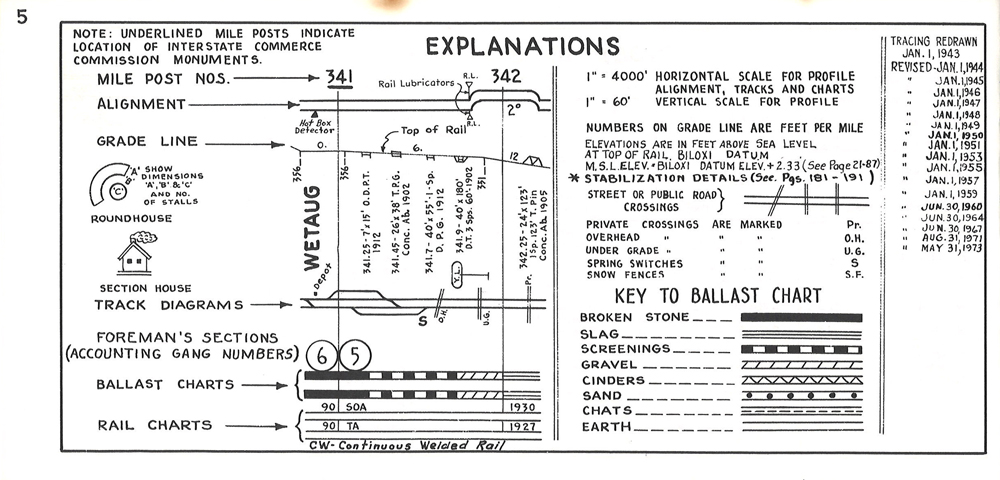

As shown in the “key to ballast chart” above, a variety of materials can be used for ballast. Examples of broken stones include granite, limestone, and quartzite. Slag is a waste product from steel manufacturing that’s crushed into rock-sized pieces. Broken stones and slag were used on the Illinois Central Gulf (ICG) main line between Fort Dodge, Iowa, and Omaha, Neb.

The individual rocks used for main line ballast range in size from 1-1/2” to 3-1/2”. The hard rocks are non-porous and have angled edges that lock together well. Since the material is often sourced from nearby quarries, the type of rock and color varies between railroads. In some cases ballast can become the signature of a railroad. Chicago & North Western’s famous “Pink Lady” quartzite ballast was sourced from a quarry in Rock Springs, Wis.

The ballast used on branch lines, in yards, and on industrial spurs may be broken stone and/or slag, but more often it’s cheaper materials like gravel, cinders, sand, and chats (waste from lead-zinc mining). On the ICG Sioux Falls District, gravel and chats were the two primary ballast types. Gravel ballast was also used on the spur leading to the trailer-on-flatcar ramp at Crookston, Minn., as shown above.

Roadbed sections

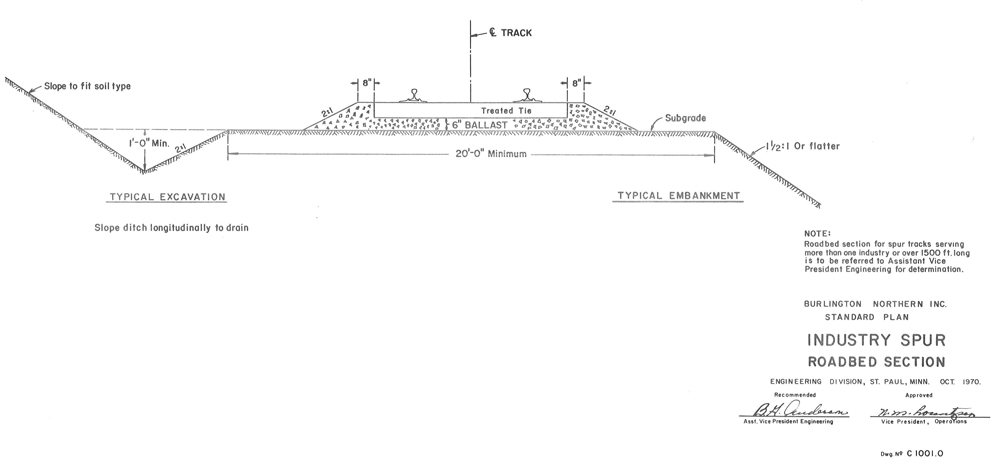

Most major railroads published books with standard plans for trackwork. A few years ago I came across a March 1974 edition of Burlington Northern’s Roadway Standard Plans from a used book dealer. Inside the book were illustrations of roadbed sections for industry spurs, single- and double-track main lines (tangent and on curves), and light-traffic lines.

One of the items the illustration above shows is ballast depth. On light-traffic lines, industry spurs, and passing sidings there’s generally 6” to 10” of ballast between the bottom of the ties and the subroadbed. On heavy-traffic and high-speed lines, the ballast depth may range from 12” to 18” or more.

Ballast depth can also vary by era, so it’s best to refer to roadbed section illustrations whenever possible. Original railroad standard plan books show up occasionally at used book dealers, railroad swap meets, and online auction websites. Since these were internal, limited-run publications, they can demand a premium price.

Reproduction standard plan books have been offered by some railroad historical groups over the years, including the Santa Fe Ry. Historical and Modeling Society, the Soo Line Historical & Technical Society, and the Southern Ry. Historical Association.

Maintaining ballast

Ballast, like most things on the railroad, requires regular maintenance. Over time ballast begins settle and lose its shape. In addition, rock fragments from worn ballast, spilled commodities, locomotive sand (used for traction), and soil can prevent proper drainage.

Railroads and contractors often use self-propelled equipment to maintain ballast. Tamping machines, or tampers, are used to level the rails and redistribute ballast between and below the ties. Regulators are equipped with plows and wings to shape the ballast profile. The broom, fitted with fiber-reinforced rubber whiskers, remove rocks from the tie tops and do the final dressing.

In other instances, railroads may hire contractors to help with ballast maintenance. Loram, a railroad maintenance-of-way company, provides various services such as shoulder ballast cleaning and undercutting.

If ballast maintenance is deferred for an extended period, a void may form between the bottom of the ties and the subroadbed. As trains pass, the weight of the locomotives and freight cars will press the rails and ties into the soil. If conditions are wet, the ties will pull mud into the ballast as they spring back up. This is called mud pumping. The photo above shows an example of this near a grade crossing. The mud has contaminated the ballast to the point that water isn’t draining properly and there’s standing water between several of the ties.

On your layout

A few months ago I posted my article “Tips for successful ballasting” on Trains.com. In the story, I explained the different types of ballast you can use on your layout; various tools, glues, and wetting agents; and my favorite ballasting techniques.

Fortunately, we don’t need all sorts of machinery to build up the roadbed on our model railroads. Instead, we can use cork, Homasote, foam, and other off-the-shelf products. However, we can use roadbed to reflect height variations found on the prototype. Industrial spurs can be laid directly on the layout surface.

In addition to roadbed height and rail code, the type of ballast used can give operators and visitors clues as to what different tracks are used for. Track that has crushed-rock ballast and is free of weeds is most likely the main line. Depending on the era, sidings and yards will be ballasted with gravel, cinders, chats, or similar materials. Secondary tracks may also have a few weeds between the ties.

Ballast can also help reinforce the era of your layout. Contributing editor Tony Koester’s HO scale Nickel Plate Road (NKP) St. Louis Division layout is set in the fall of 1954 when steam and diesel locomotives were operating side-by-side. Following a roadbed section diagram from the prototype, Tony used cinders for the subroadbed and crushed rock (Arizona Rock & Mineral No. 1382) for the ballast on the main line. Cinders were typically smaller than crushed rock. If you model in HO scale, consider using N or Z cinders as they’re more realistically sized.

Contributing editor Pelle Søeborg’s HO scale Union Pacific Daneville Subdivision layout effectively illustrates many of the ballasting tips and techniques covered here. In the photo above, the two mainline tracks are higher and the ballast has a well-defined profile. The two sidings are lower, and there’s some ballast on the tie tops. Similar to Paul J. Dolkos, Pelle added a few weeds next to the siding.

A small thing Pelle did in this scene was mix gravel from the road into the ballast on the adjacent siding. It’s subtle, but the gravel gives the ballast an uneven edge, much like you’d see on the prototype.

You can learn more about Pelle’s techniques in his article “How to make track look realistic” in the July 2013 issue of Model Railroader.

Check out Jeff Wilson’s all-new book Modeler’s Guide to the Right of Way for more information on track and roadbed, grade crossing and trackside details, signs, and more. The 112-page book is available on the Kalmbach Hobby Store website and at hobby shops that carry Kalmbach Media products.