Meet Dominic Bourgeois

What was your first train set (or locomotive)?

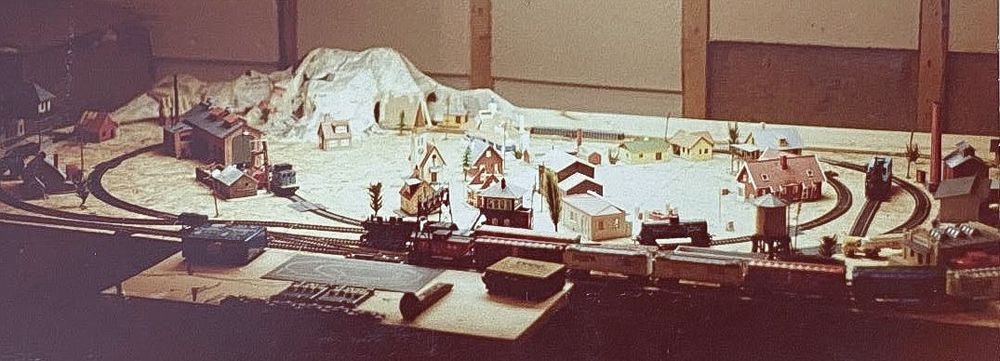

I was only 6 years old and so I don’t quite remember, but I’m reasonably confident that it was a Model Power set that included a Baldwin “Shark” diesel painted in the Canadian National striped scheme and maybe two cars, a caboose, and a circle of track. My dad bought a bulletin board to set the track down in a more permanent fashion, but it only measured 36”x 48” and the 18”-radius curves had to be kinked tighter to fit. For some reason, it was not to be, and the set disappeared.

But some interest in trains did remain and by Christmas at age 13, my parents ordered a small Life-Like starter set for me. The store made a mistake and delivered a larger set, including a CN-painted GP38-2, probably five or six cars and an oval of track. This time, a 4’ x 8’ sheet of particle board formed the base. Like most mass-market train sets of the time, this one had a poor-running locomotive and oxidation-prone brass rails. I was hooked enough to purchase an Athearn GP35 painted in Soo Line colors on the advice of the local toy and hobby store owner. That model ran well, so my interest in the hobby only increased from then on. I also discovered Model Railroader at the time, which was fortunate.

Describe your model railroading philosophy in 6 words.

How about four words? “Prototype modeling is addictive.” When I first delved into the hobby, I did like anybody else would and modeled “whatever.” Then I gradually learned that modelers of the time almost universally adopted a “proto-freelancing” mode, where they modified reality to suit their modeling needs and tastes. That approach encompasses a full spectrum of options, ranging from a basic recognition of reality, to the elaboration of a full-blown rationale, and perhaps even a complete history, for a freelanced but quasi-prototype-based railroad set in a specific time and place.

I did something highly unusual: I created a freelanced railroad (the Vermont & New England RR) that ran on a layout that correctly replicated the actual Centra Vermont RY’s right-of-way and environment. I enjoyed visiting St. Albans, Vt. and building a miniature version of it. My modeling and railfan friends could relate to what I was building, and that dynamic proved motivational. I was a member of a club at the time and within a few years an organized field trip to Albany, N.Y., coincident with a related series of articles in Railroad Model Craftsman, resulted in a superseding interest in the Delaware & Hudson RY. I soon transitioned to a strictly prototypical approach, having already almost reached that point anyway, and never looked back.

While I understand that most modelers prefer to freelance, no doubt motivated by a perfectly understandable need for self-expression and a wish to avoid the feeling of being constrained in the hobby, I had discovered that the world was a very interesting place, worthy of replication as-is. If one makes the effort to carefully observe the real environment around a railroad, all kinds of neat, appealing features that you wouldn’t necessarily think of on your own become apparent, generating interesting modeling projects and often leading to the learning of new skills. To me, another aspect of prototype modeling is that it allows me to run trains or take photos at a time and in locations which I did not have the opportunity to experience firsthand, but wish I had. The research work that became necessary, especially since I chose to represent the year 1975 rather than present-day, also proved thoroughly enjoyable. Research is definitely time consuming, a kind of hobby within the hobby, in fact, but railfanning and field trips are fun and inspiring, while exploring relevant media is often eye-opening. Finally, there’s the thrill of the chase for that elusive bit of data or ultra-rare accurate model produced years ago.

Prototype modeling is easier than ever, though, considering the recent influx of highly detailed, accurate models on the market, as well as the wealth of research material now readily available online and in print.

What was your biggest modeling mistake?

“Make only new mistakes” is an oft-repeated adage, but real life doesn’t work that way. We just can’t know everything there is to know before diving into a project. I’ve made countless mistakes in the past, and I continue to make them. It doesn’t matter. With a bit of experience, most mistakes in the hobby can readily be fixed (or disguised). As long as a given mistake doesn’t result in the house burning down or a lost limb, the penalty is minimal, and you end up learning something from it. Luckily, I did manage to avoid the relatively major mistakes of building poorly aligned track or sub-par benchwork.

I’m dodging the question, aren’t I? Well, here’s my stupidest mistake: A long, long time ago, I found out that you could bake paint after applying it to a model to make it adhere better. I set the temperature on the toaster oven quite low and monitored the process through the glass window. One partially melted plastic diesel shell later, I learned that this technique only applied to brass models. I fixed the shell so that it looked passable enough to put in service, but in retrospect, I could have more readily turned it into a wrecked unit parked by the roundhouse.

What’s your least favorite modeling task?

I don’t think there’s anything I really dislike about the hobby. Sure, there are times when I’d rather not have to do wiring, hand lay an umpteenth turnout, or scratchbuild the 23rd structure necessary for a prototype scene (after having built the previous 22 more appealing ones), or re-map the functions on another DCC sound decoder, but then, at times, the urge to do those things does hit me. Most of them are thankfully not long-term commitments, so they are not terribly burdensome. All offer some degree of satisfaction, at least when completed, if not always while underway. Having said that, cleaning track and wheels is never fun.

What project(s) have you been working on recently?

I’m working on the Delaware & Hudson’s Mohawk Yard on the outskirts of Schenectady, N.Y. Like all the railroad’s locations I’ve previously modeled, the scene consists of a series of individual modules that can be moved easily at home or brought to train shows, or even, best of all, be flipped over to make the task of wiring more comfortable.

But that’s just one thing. I always have several different smaller projects underway concurrently with the more long-term endeavors. I never get tired of working on rolling stock, for instance. In fact, I frequently pick up a previously completed freight car or locomotive and decide to make some improvement to it because I’ve found better reference material, or my skills have improved in the interim. I’ve made an effort in recent years to work through my stockpile of still-in-the-box rolling stock, adding appropriate paint, details and weathering, and I managed to actually complete nearly all of them. Since I continue to acquire more rolling stock (like all of you, no doubt), I now make sure I “process” them as they come in rather than letting them accumulate untouched. Yes, it takes some discipline, but it guarantees every new purchase is essential to the theme, rather than just an impulse buy.

What advice would you give to a new hobbyist?

To persevere. Every single advanced or highly skilled hobbyist we admire today started out as a beginner at some point. There’s no getting around the fact that it will take a bit of time to learn the basics, but in this information age it will not take all that long. Joining a club or round-robin group can also be very helpful. You will learn new skills from real people and make new friends along the way, which is a good thing. Once you’ve mastered the basics you need to be functional, you’re essentially cruising at your own pace. The projects you undertake will shape your skill set; each one promises new challenges and delivers enjoyment while underway or when completed.

Oh, and learn to disregard the rudest critics. That wasn’t much of a problem when I started, but it’s unfortunately become more common in today’s anonymous cyberspace, in this and most other spheres of society. Critics, or self-proclaimed experts, expect perfection and will accept nothing else… from others. Understand that they themselves often don’t actually build anything, let alone complete a layout, and you will feel liberated. The best modelers out there are almost universally nice people who do remember that they were once beginners, and they will generally refrain from expressing harsh criticism. They will, however, offer valuable advice when asked. Ultimately, though, you’re in this hobby for your own enjoyment, so the only person you need to please is you. Go for it!