The story of the Union Pacific Challengers has been told many times. It’s enough to know that the 65 engines represented by the Genesis model were built by the American Locomotive Co. (Alco) during World War II. These Challengers were used in freight, passenger, and helper service until 1959. One, the 3985, was returned to excursion operation in 1981.

More history can be found in the booklet included with the model, or you can refer to my article, “Challenger 3985 and her sisters,” in the January 1995 Model Railroader.

Overall, the model’s detailing is excellent, with finely molded rivets and other surface features. There are many separately applied plastic, metal, and wire parts, and in general their effect is quite good. Particularly noteworthy are the see- through holes in the running boards, and the sanding nozzles just in front of the second and third drivers on each engine. I like seeing the sections of the smoke hood (non-operating) inside the smokestack casing, and I also appreciate the rarely modeled radius on the rear corners of the cab, a common Alco feature.

The metal rods and valve gear have a realistic steel color, and the eccentric cranks are correctly angled on both sides. Unfortunately the crossheads and piston rods are black plastic. The piston rods especially ought to appear to be natural metal, since paint can’t be used where they pass through the packing glands into the cylinders.

The model is extremely close to its prototype in all measurements. The tender and trailing truck wheels are the correct 42″ diameter, while the pilot wheels are 33″ instead of 36″, and the drivers 67-1/2″ instead of 69″. Manufacturers often compromise on driver diameter because of oversize model flanges, so it’s good to see that this Challenger’s drivers come so close.

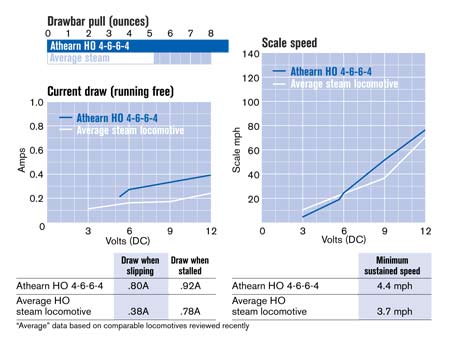

As is typical of locomotives equipped for DC-compatible sound, the starting voltage is a bit high. However, the locomotive comes with a push-button radio control unit that allows you to set a maximum voltage with your power pack and then enjoy wireless control of the engine’s speed, direction and sound effects. This wireless controller is also used for sound system programming, a definite step up in ease of DC operations.

(To get voltage and current readings with our test meters, I controlled the engine’s speed and direction with a power pack for our performance tests.)

The Challenger’s decoder automatically recognizes a DCC signal on the track and switches into command control operation. More sound effects are available in the DCC mode, and I found it easier to blow whistle signals using the function button of a DCC cab than with the radio-control unit. The engine’s exhaust-sound rate is adjustable with a configuration variable (CV), but the factory setting produces the correct (for both engines “in step”) four chuffs per driver revolution.

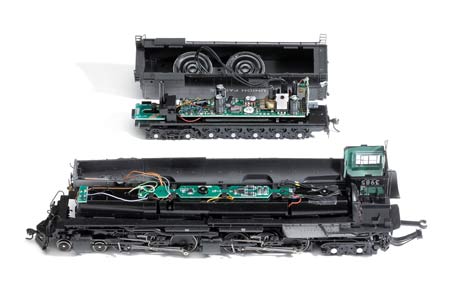

The sound effects play through two downward facing speakers enclosed in the tender, and volume can be manually controlled using a potentiometer under the tender’s middle water hatch. Those using DCC can also control the volume with a CV. In general the sound effects are good, although there’s quite a staccato attack to the chuff sound, and I’ve heard better coupler clanks from other systems.

Wheels and couplers. All the Challenger’s pilot wheels and drivers matched the National Model Railroad Association standards gauge, but the trailer and tender wheels – all the 42″-diameter wheelsets – were slightly narrow in gauge. The locomotive and tender operated satisfactorily through Atlas turnouts.

All twelve drivers and the forward eight wheels of the tender’s pedestal truck pick up current from the rails. That gives the Challenger ten pickup wheels on each side, although the traction tires will keep the rear drivers from picking up unless the flanges make contact.

The rear coupler on the tender is the correct height, and a magnetic knuckle coupler is included to replace the swing-gate dummy coupler on the pilot. It’s the correct height when installed with the supplied coupler box support and mounting screw.

As has unfortunately become typical for articulated models, both engines pivot on this locomotive, instead of the rear engine being rigid with the front engine hinged from it. The steam pipes can’t connect to the rear cylinders as they should, and the gap is noticeable on sharp curves. Although the Challenger can negotiate 18″-radius curves, I second Athearn’s recommendation that it be used on curves of 22″ or larger radius. It looks far more realistic on 30″ to 36″ curves.

A Challenger for your roundhouse? The UP Challenger is a popular locomotive that’s been modeled before, but there hasn’t been a better mass-produced model of this prototype than this one. It’s also good to see a model with built-in sound and DCC in the Genesis line, both features that add to the fun of model railroading. If there’s a stall for a 4-6-6-4 in your roundhouse, you’ll be happy to fill it with Athearn’s Challenger.

Automatic dual-mode

(DC/DCC) control and sound

system

Cab interior with backhead

Constant directional headlight

and backup light

Coupled wheelbase: 107′-3″

(requires a 15-1/2″ turntable)

Drawbar pull: 8.8 ounces (with

two traction tires)

Enclosed motor with two

turned-brass flywheels

Engine and tender weight: 35.75

ounces (engine alone weighs

26 ounces)

Illuminated train indicators

(“numbered boards”)

Magnetic knuckle couplers

Minimum radius: 18″, but 22″-

radius is recommended

Opening cab ventilator

Sliding cab windows

Wheel flanges: .035″ deep

except drivers, .025″ deep