Electro-Motive Division was a relative latecomer to the road-switcher market, following successful entries from Alco and Baldwin. The new hood unit was designated the GP7, GP for “general purpose” and 7 because it used the same 1,500-hp engine as EMD’s F7 cab unit.

The locomotives were a huge success for General Motors. Between October 1949 and May 1954, 2,610 GP7s were sold to American railroads; 112 more went to Canada, and two to Mexico. (Its similar-appearing successor, the 1,750-hp GP9, was an even bigger smash, with more than 4,000 built.)

The GP7 saw service on almost every North American railroad, pulling everything from branchline freights to mainline passenger trains. Passenger units were equipped with steam generators to provide heat for coaches; our sample is a freight version, without the steam generator. The GP7s could be ordered with or without dynamic brakes.

The locomotives proved to be not only great sellers, but solid performers. Rather than scrap them when new models came out, many railroads chose to have them rebuilt, such as the Union Pacific’s GP7M. A good number of GP7s, rebuilt or not, are still serving short lines and excursion railroads today.

The devil’s in the details. The body dimensions and detail placement of the Bachmann model match diagrams in Model Railroader Cyclopedia vol. 2: Diesel Locomotives (Kalmbach Books, out of print). The Bachmann model is of an early-production GP7, often referred to as “phase I” by railfans. Phase I GP7s were built between October 1949 and August 1952. These diesels had solid side skirts rather than the slotted side skirts of later production GP7s.

Our sample is decorated for the Pennsylvania RR. The almost-black “Brunswick Green” paint is smoothly applied. The yellow lettering is sharp, opaque, and correctly aligned. The clear, flush-fitting cab window glazing is framed in crisp chrome paint.

The Bachmann GP7 is available with or without dynamic brake blisters, depending on the road name. Though many Pennsy Geeps had dynamic brakes, the model correctly depicts PRR no. 8805 without them.

The finely molded, flexible plastic handrails are painted yellow in the prototypical locations.

There were a number of discrepancies between our model and the prototype PRR no. 8805. For instance, the prototype had m.u. hoses on the pilot, m.u. stands, and a trainphone antenna, all of which are absent on the model.

Other inconsistencies include the wrong lettering style on the cab number; the yellow “F” designating the locomotive’s front is on the wrong end (the Pennsy ran its road switchers long hood forward); and the horns, similarly, are on the wrong hood.

Grab irons on the ends of both hoods are missing from the model. Details West and other firms sell wire grab irons as well as metal m.u. hoses and stands that would be appropriate for the model.

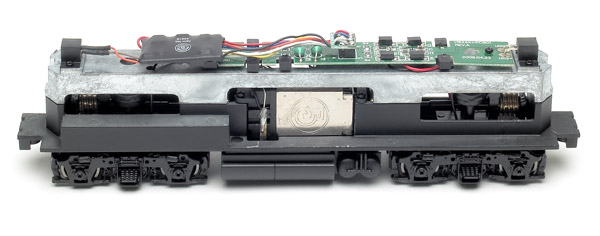

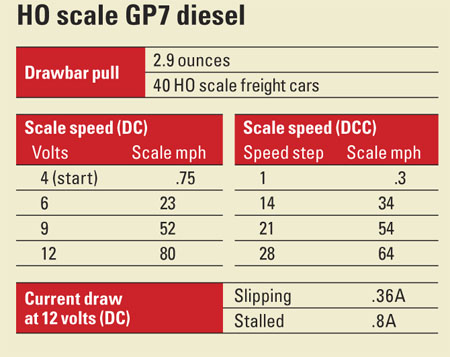

A can motor is nestled in the center of the die-cast metal frame. Two brass flywheels are concealed in recesses of this frame, between the motor and the two worm gears that drive all four axles of the model. This all-wheel drive gives the model plenty of power; our digital force meter showed the GP7 could pull a train of 40 HO scale freight cars on straight and level track.

A printed-circuit (PC) board for lighting extends almost the full length of the top of the frame. The DCC decoder is attached to this board via a standard 8-pin wiring harness; Bachmann provides a jumper board for this socket in case you want to operate the locomotive under direct current only. The decoder is dual-mode, meaning it allows normal DC running, but operating it under DCC sets a decoder Configuration Variable (CV) that locks it into DCC mode. Going back to analog operation requires subtracting 4 from the value of CV29.

The decoder sits under the part of the hood occupied by the cab, but the locomotive’s inner workings aren’t visible through the cab windows. There is a small amount of space between the cab sides and the shell’s inner walls; carefully removing the cab would let a modeler add figures.

In DCC operation, using 28 speed steps, the engine at first didn’t move until speed step 6. Using the Model Rectifier Corp. Prodigy Advance system on our test bench, I reprogrammed the decoder’s starting voltage (CV 2) to 255, the maximum. The locomotive then responded to speed step 1 at a halting, but still impressively slow, 0.3 mph. At speed step 28, it moved at 64 mph, almost exactly the prototype’s top speed.

Switching to 128 speed steps had an odd effect: it caused the locomotive to race along at almost 20 scale mph at speed step 1. I experimented with some different values for CV 2, finally settling on 210. The model then rolled along at less than 1 scale mph in speed step 1. After I reprogrammed its starting voltage, the locomotive, in general, responded and operated much more smoothly under 128 speed steps.

The Bachmann GP7 diesel has good performance and plenty of pulling power for the tasks typically assigned to a four-axle road switcher. The model does lack some details, such as grab irons and m.u. hoses, but could provide the foundation for a fun superdetailing project.

Price: $89

Manufacturer

Bachmann

1400 E. Erie Ave.

Philadelphia, PA 19124

bachmanntrains.com

Road names: Pennsylvania RR, Baltimore & Ohio, Chessie System (B&O reporting marks), Clinchfield, New York Central (lightning-stripe scheme), and Union Pacific

Era: 1949 to present

Features:

All-wheel drive and electrical pickup

Dual-mode Digital Command Control decoder

Light-emitting-diode headlights

Magnetic knuckle couplers, mounted at correct height

Painted flexible plastic handrails

RP-25-contour metal wheels mounted in gauge

Weight: 15 ounces

Wire uncoupling levers