100 years of history. In the mid-1960s, Electro-Motive Division started experimenting with locomotives that combined two engines in one. The first was the DD35B, essentially two GP35s joined back-to-back. The DD indicated its two four-axle trucks, and the B stood for “booster,” meaning the locomotive was cabless. In 1963 and 1964, 30 DD35Bs were sold to the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific, the latter of which asked EMD for a similar unit locomotive with a cab. The result was the 5,000-hp DD35A, 15 of which were delivered in 1965.

In 1969, EMD offered a larger version, the DDA40X. The 40 indicated that the locomotive’s engines were the model 645E3As used in the GP40, and the X stood for “experimental.” Not only was it the first American hood locomotive to have a wide nose, it also was a test platform for the modular electric controls that would become standard in EMD’s Dash 2 line.

All 47 of the DDA40Xs built went to the UP, which called them “Centennials” to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the driving of the Golden Spike. Thirteen of the locomotives survive, all but one on display in various museums; the exception is no. 6936, still in service as part of UP’s Heritage Fleet.

The model. Bachmann’s HO scale DDA40X (the company sells it under the misnomer DD40AX) features a finely molded plastic body shell on a split-frame die-cast metal chassis. The body’s major dimensions match those on a Union Pacific diagram reprinted in George R. Cockle’s book Giants of the West (Overland Publications). The model has plastic handrails, wire grab irons, and molded-in lift rings. The lettering is straight and crisp, and the paint is even and opaque.

From the side, one of the flywheels attached to the rear motor is visible in the walkthrough in the center of the HO locomotive’s body. On the prototype, this opening is unobstructed.

The front of the model’s die-cast metal frame intrudes into the cab and is visible through the front windows. Also, the hood has 10 shorter doors under the lower portion of the dynamic brake intake, which matches UP drawings, but not prototype photos.

A look inside. Under the plastic body shell, a printed-circuit board (PCB) runs the full length of the top of the die-cast metal frame. The model has two dual-flywheel-equipped can motors, one for each truck. All eight axles are driven, and all 16 wheels pick up power.

Light-emitting diodes for the headlights, backup lights, classification lights, and number boxes are attached to the inside of the shell. There is also an LED rotary beacon on the cab roof that blinks when the locomotive is in motion.

A DCC decoder is mounted vertically in an open space between the two motors and connected to the PCB via a standard eight-pin wiring harness. If you want to replace it with a sound decoder, choosing one 5/8″ x 13/16″ or smaller will allow it to fit in the same space. The inside of the fuel tank has space to mount two downward-facing speakers, and there are holes to emit sound in the bottom.

Although the instructions state that the decoder has only 28 speed steps, it actually does support 128 speed steps for finer speed control.

On DC, the model was also a bit jerky at low speeds, but smoothed out as I advanced the throttle.

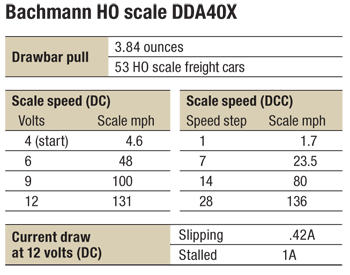

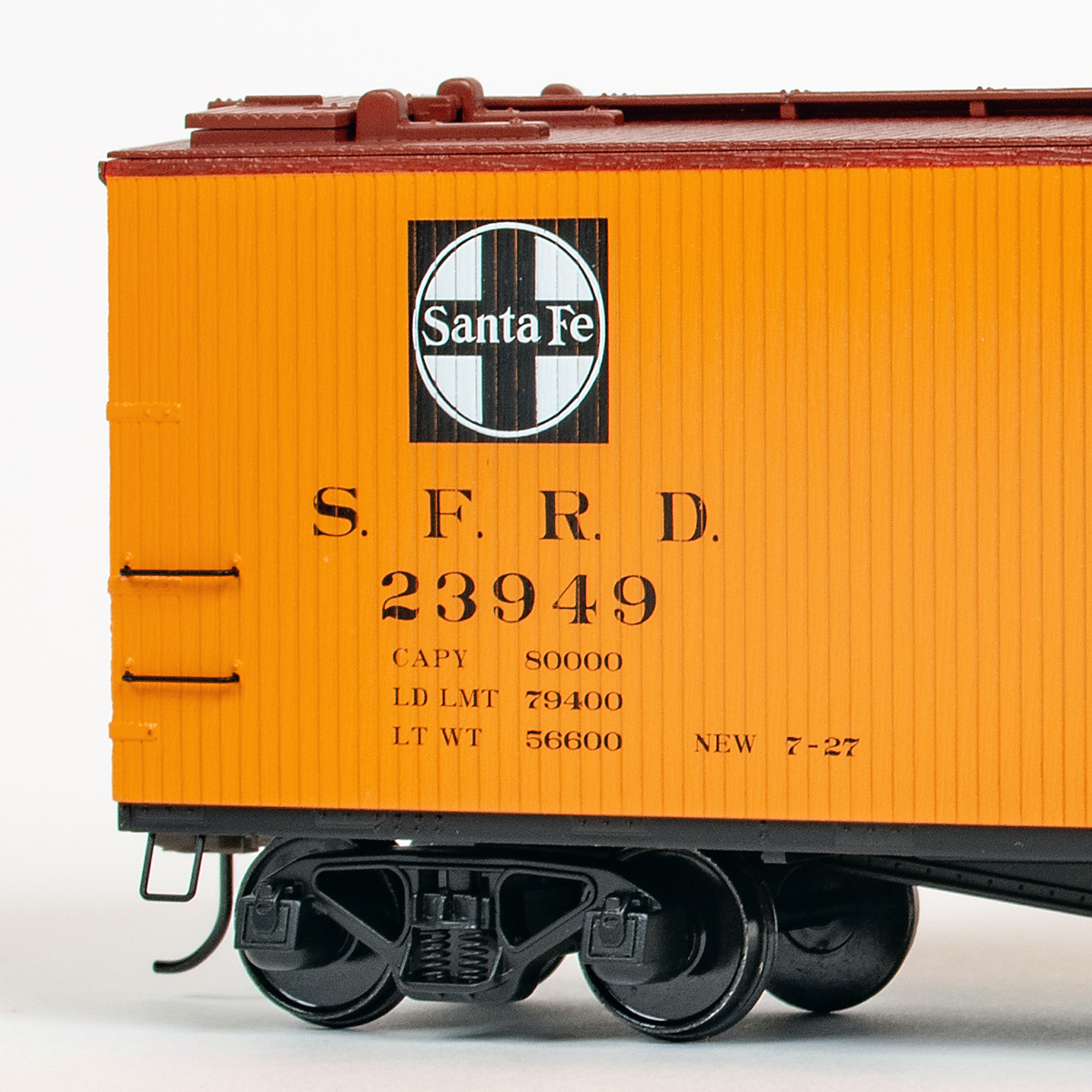

With its two motors, our DDA40X measured up to its prototype in pulling power. The meter on our test bench measured nearly 1/4 pound of drawbar force, enough to pull 53 free-rolling freight cars on straight and level track. The model comes equipped with E-Z Mate Mark II magnetic knuckle couplers, which were mounted at the correct height.

As might be expected with such a long wheelbase, our DDA40X prefers broader curves. Bachmann recommends no smaller than 24″ curves for this model, and bigger would be even better.

A UP icon. If you model Union Pacific’s western main lines from 1969 into the 1980s you’ll want at least one of these monsters. This model would look right at home dragging a long fast freight.

Price: $125

Manufacturer

Bachmann Trains

1400 E. Erie Ave.

Philadelphia, PA 19124

www.bachmanntrains.com

Road numbers: (all Union Pacific) No. 6915, 6927, 6932, and 6943

Era: 1969 to present

Features

All-wheel drive and electrical pickup

Chemically blackened wheels, in gauge, with RP-25 contour

Directional light-emitting-diode lighting

Dual-mode Digital Command Control decoder

Flashing rotary beacon on cab

Lighted number boxes

Minimum radius: 24″

Truck-mounted E-Z Mate Mark II magnetic knuckle couplers, at correct height

Two skew-wound can motors with dual flywheels

Weight: 1 pound, 7 ounces