Spotting features. The F7 was one of General Motors Electro-Motive Division’s most successful diesels ever, with more than 3,800 A and B units combined sold in the United States, Mexico, and Canada. The F units were ubiquitous on North American rails, cementing EMD’s dominance in the diesel market for years to come. Built between February 1949 and December 1953, many F7s lasted in revenue service into the 1980s, and some are still working today on short lines and tourist railroads.

There’s a strong family resemblance between the models in EMD’s F series. The easiest spotting features between the different “phases” – a railfan term for changes in construction details over time – are the side grills and air intakes. The Phase I F7A was visually identical to the Phase IV F3A. Both locomotives had horizontal-slit Farr-Air grills on the upper carbody sides, four horizontal-louver air intakes on the sides, square windows in their end doors, and a 36″ dynamic brake fan on the roof. Phase II F7As had a 48″ dynamic brake fan, vertical-slit grills, vertical louvers, and a round porthole in the end door.

Bachmann’s model represents a Phase I F7, built before November 1951. However, just as on Bachmann’s HO model, the N scale F7A has the Phase II’s 48-inch dynamic brake fan, a feature not introduced until August 1952.

Looking it over. The paint job on both the A and B units is superb. The silver is smooth and even, the red is vivid and opaque, and the thin black and yellow stripes between them are without voids, feathering, or overlaps. Even the tiniest printing, like the “F” at the front end and the “Water” label in the lower red stripe, is legible under magnification.

Most of the locomotive’s details are molded in place on the plastic shell, including grab irons, ladders, and stirrup steps. The horns were separately applied, as were the nose’s angled number boxes, which were blank on our Santa Fe sample model and most of the other road names offered.

The body shell lacks a few details, such as nose and “eyebrow” grab irons and windshield wipers. The glazing isn’t flush in the cab window frames, and the porthole windows lack glazing.

Most of the major dimensions of the locomotives match those in drawings I found in official EMD publications in our library. The coupled distance between the N scale A and B unit is 2 scale feet wider than the prototype.

There were some minor detail discrepancies. The rearmost side intake grill, along with its adjacent sand filler hatch, should be almost a scale foot farther forward, closer to the rivet line. The nose light protrudes more on the model than on the prototype. The F7 was offered with a choice of one or two nose lights. All the photographs of Santa Fe passenger F7s I could find had two, while the model has only one.

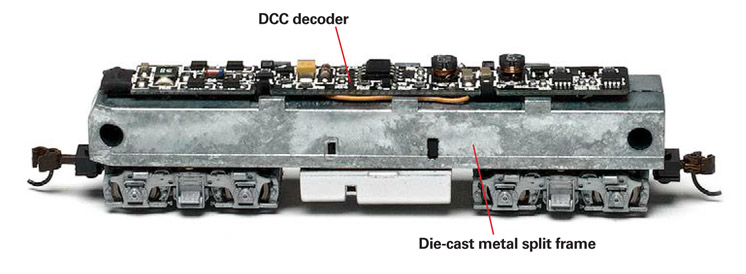

The model’s can motor, flywheels, and gear towers are completely enclosed within the halves of a split die-cast metal frame. The decoder is secured in a pair of plastic clips on top of the frame. Electricity is passed from pickup wipers on both trucks to the two halves of the frame; the decoder has a pair of contacts on each end that pick up current from the frame. On our A unit, I noticed

that the front truck’s wipers didn’t touch the frame, making the locomotive less tolerant of dirty track. I unscrewed the frame, bent the contacts up slightly, and reassembled the mechanism, improving the engine’s performance.

Though I’m not aware of any sound decoders specifically made to replace the DCC decoder that comes in Bachmann’s N scale F7s, the plastic clips that retain the stock decoder can be easily slipped out of the frame, leaving plenty of space atop the frame for an N scale decoder and button speaker. The only wiring required would be attaching two wires to the frame and two to the motor.

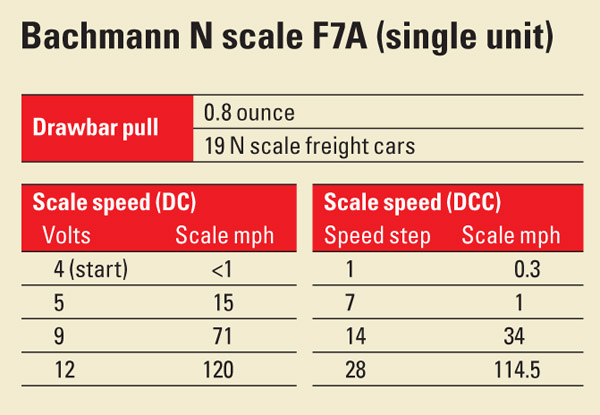

The yellow LED headlight came on at 3V. At 4V the locomotive moved so slowly I could count the number of ties it passed in 30 seconds on my fingers. At 12V, it reached a top speed of 120 scale mph, higher than the prototype’s highest top speed gearing of 102 mph.

Under DCC, the locomotive displayed even better slow-speed performance. The locomotive’s motor buzzed at speed step 1, but the locomotive didn’t move. I used our NCE Power Cab DCC system to program Configuration Variable (CV) 2, which governs the motor’s starting voltage, to a value of 31. After I did so, the engine responded to speed step 1 by moving at 0.3 scale mph.

Even after I increased CV2, the engine’s speed curve seemed weighted toward the low end of the scale, rolling at just over 1 scale mph at speed step 7. The Bachmann decoder doesn’t support CV5 (top voltage) and CV6 (mid voltage) or selectable speed curves. However, setting the decoder’s speed steps from 28 to 128 made a big difference and provided much finer control.

The model’s drawbar pull is shown in the chart above. An A-B set should easily pull 38 free-rolling N scale freight cars on straight and level track.

The A-B set also had no problems pulling a 10-car passenger train around our N scale Salt Lake Route layout’s no. 6 turnouts and 10″ radius curves.

An icon. If there’s a more iconic example of a diesel locomotive than an EMD F unit wearing Santa Fe red and silver, I haven’t seen it. Bachmann’s version of this classic locomotive looks sharp, and after a few simple adjustments runs great.

Manufacturer

Bachmann Industries

1400 E. Erie Ave.

Philadelphia, PA 19124

www.bachmanntrains.com

Road names: Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (warbonnet); Baltimore & Ohio; Erie Lackawanna; Great Northern (green and orange); and Norfolk Southern.

Era: 1949 to 1980s

Features

- Blackened metal wheelsets, in gauge (all pick up power)

- Directional LED headlight

- Five-pole skew-wound motor with dual brass flywheels

- Knuckle couplers mounted at correct height

- Minimum radius: 93⁄4″

- Separately applied number boxes (blank on most road names)

- Split die-cast metal frame

- Weight: 3.5 ounces (A unit),

- 3.75 ounces (B unit)