Detailed and smooth-running steam locomotives are cause for celebration among N scalers. They’re even more so when the engines in question feature onboard Digital Command Control (DCC) and sound. That’s the case with the latest offerings from Broadway Limited Imports, a pair of Pennsylvania RR 4-8-2 Mountains ready to haul fast freight on your N scale PRR layout. These sharp-looking models come equipped with BLI’s powerful Paragon2 DCC sound decoders, delivering precision control and authentic sounds.

Mountain muscle. The first 4-8-2 steam locomotive was built by Alco in 1910 for the Chesapeake & Ohio, which named it “Mountain” for the Appalachian terrain it was designed to conquer. It would be 13 years until the Pennsylvania RR would field its first 4-8-2, a test engine designated class M1. The engine was heavier than the United States Railroad Administration’s standard Mountain design, also having larger cylinders and drive wheels and higher boiler pressure. Based on the PRR’s class I1s Decapod and using the same boiler, the M1 was field tested for three years before Pennsy felt comfortable ordering 200 more from Baldwin Locomotive Works and Lima Locomotive Works.

The Pennsylvania RR’s next 4-8-2 order, for 100 more engines, were equipped with Worthington feedwater heaters, visible as rectangular boxes atop the smokebox, directly behind the stack. Other improvements include a one-piece cylinder block and smokebox saddle casting with internal steam delivery pipes. Rostered by the PRR in 1930, these engines were designated class M1a. In 1946, some of these engines were refitted with uprated boilers for even higher steam pressure, as well as water recirculators, and designated class M1b. The external cleanout plugs for these recirculators, seen on the side of the locomotive’s distinctive Belpaire firebox, is the only external difference between the M1a and M1b classes.

The M1 family was designed for use pulling both freight and passenger trains, and a few were decked out in simulated gold trim for passenger duty. Broadway Limited’s N scale versions are all painted in the unadorned freight scheme. Many remained in service up until the Pennsy ran steam for the last time in 1957. M1b no. 6755 is preserved on display at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, Pa.

Outside and in. We looked at both no. 6743, a pre-war detailed class M1a, and no. 6704, a post-1946 detailed class M1b. Both models are flawlessly painted in “almost black” Dark Locomotive Green Enamel with dark graphite smokeboxes. The PRR Buff lettering on the tender and cab sides is crisp, opaque, and free of voids. Under magnification, the lettering on the back of the tender is legible, and the builder’s plates on the smokebox nearly so. Like their prototypes, the models have keystone-shaped smokebox numberplates.

All the dimensions I checked matched up with those on drawings of a PRR class M1a in Kalmbach Publishing’s Model Railroader Cyclopedia: Vol. 1, Steam Locomotives (1960). The drawing shows a freight engine, with the brakeman’s “doghouse” on the rear of the long-haul “coast-to-coast” tender, like that on BLI’s model.

The wheels on both models were in gauge, according to the National Model Railroad Association standards gauge. Like the valve gear, the wheels are chemically blackened. Just like the prototype, the middle four drivers are “blind,” or flangeless, letting the engine more easily navigate sharp curves and turnouts. The rear drive axle has traction tires.

Removing two tiny screws below the back corners of the cab and one above the lead truck allowed me to carefully lift off the plastic locomotive shell. The can motor and its brass flywheel filled the firebox. The rest of the boiler was occupied by a cast-metal weight, which gave the locomotive its 3.5 ounces of weight. The engine’s Paragon2 Digital Command Control sound decoder and speaker are housed in the plastic tender. The tender is topped by a shiny, molded plastic coal load. The magnetic knuckle coupler on the rear was mounted at the correct height on both models. (The front couplers are dummies on both.)

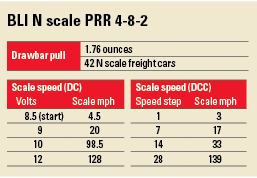

Performance. Since the two models are internally identical, I did all my testing on no. 6743. I first ran the engine on direct current.

Like most other dual-mode sound-decoder equipped engines, the M1a took a lot of voltage to get started. At first, I had difficulty getting the engine to start gently. But then I realized that if I let the engine sit at about 7V for a few seconds, the headlight would come on, the startup sound sequence would play, and the engine could make a smoother start. With this method, I could make the engine crawl at less than 1 scale mph, although I noted some hesitation. At 8.5V, the engine rolled more steadily.

This didn’t leave a lot of range on the throttle for fine control of the engine’s speed. At 10V, it was already surpassing the prototype’s top speed of 90 mph. At 12V, the model reached 127.8 scale mph. Later I used our Digital Command Control system to change CV5, Vmax, to a value of 128, which lowered the engine’s top speed under direct-current to a more prototypical 90 smph.

While I had the DC power hooked up, I also tested the engine with a DCMaster, a control box from BLI (sold separately) meant to be wired between a DC power pack and the rails. This four-button controller lets the user trigger the bell and horn on Paragon2 locomotive models, as well as program decoder Configuration Variables (CVs) without need for a DCC system.

Under Digital Command Control, I enjoyed much more precise control over the engine’s speed, as well as access to more sound effects, such as a coupler clank, air pump, coal auger, and a number of station announcements and background sounds.

I liked that some of the sound effects changed function depending on whether the engine was moving. For example, when stopped, F5 and F6 trigger a blow down and the water fill sequence, respectively. However, when moving, these two function keys decrease or increase the chuff intensity, great for when your engine is climbing or descending a steep grade.

Another interesting feature is the ability to record and play back “macros,” or sequences of throttle functions, thus automating the engine’s operation. I tested it by programming the engine to move forward a short distance, stop, play the bell and whistle, then reverse back to the starting point.

One handy feature for modelers using cabs with 8 or 10 function keys is that the model’s 28 functions can be easily remapped to any throttle function key.

Right on track. These BLI locomotives look as good as they sound. With their accurate details and dimensions, authentic sound, and powerful control options, beating these N scale PRR M1a and M1b Mountains would be a hard climb.

Price: $349.99

Manufacturer

Broadway Limited Imports

9 East Tower Circle

Ormond Beach, FL 32174

www.broadway-limited.com

Era: 1930 to 1957 (class M1a); 1946-1957 (class M1b)

Road numbers: M1a (pre-World War II): 6720, 6743, 6798. M1b (post-1946): 6704, 6716. Both also offered painted but unlettered.

Features

▪▪Brass bell, whistle, and safety valves

▪▪Electrical pickup on six drivers and all tender wheels

▪▪Five-pole skew-wound motor with brass flywheel

▪▪Golden-white light-emitting-diode headlight

▪▪Individually adjustable sound effect volumes

▪▪Magnetic knuckle coupler on rear, dummy coupler on front

▪▪Paragon2 sound decoder

▪▪Weight: 4.8 ounces, engine alone weighs 3.5 ounces

▪▪Wire handrails, piping, and coupler lift bars

I purchased the M1a and received it last month. Without any hesitation, I had to put it on the layout to test it. You were spot on with your findings concerning the run-up before moving. I loved the sounds as it started off then slowly fading as it picked up speed. I haven’t tried all the functions as of yet, deferring to complete my scenery. The model I purchased was an unlettered version, rebuilt and runs like a champ. BLI has done great things with the Paragon 2.

Can the dummy coupler on the front be replaced with a working coupler, and if so what would be a suitable replacement. Also, who has the best price on the locomotive. Thanx

Please indicate the speed at step 1 with 128 step dcc. I think that your reason for tabulating only 28 step performance is arcane and should be dropped in favor of 128 speed.

Thank you

The prototype M1 (all subclasses) had blind tires on the middle drivers. The PRR called them “flat tires.” The model is correct in this respect.

Any other railroads used these steam engines as did PRR or bought them after PRR finished?