Second-generation power. The real GP35 was built as a more powerful and efficient successor to EMD’s distinctive GP30. In production for just over two years, the GP35 family reached a total of 1,333 units by 1966 – the most numerous of the second-generation units. It’s a good choice for a model.

The most distinctive spotting feature of the GP35 is the smaller 36″ radiator fan between two 40″ fans. The GP40, the 35’s more-powerful and longer sibling (3,000 hp, compared to 2,500 hp), has three 40″ fans. That’s about the only way to tell them apart without counting handrail stanchions. The low short hood was standard on the GP35, though EMD built high-hood versions for the Southern, Norfolk & Western, and Nacionales de Mexico. The Micro-Trains model comes only in the low-hood version.

The model GP35 features dynamic-brake blisters on the hood and air reservoirs along the fuel tank. Prototype units were built with and without dynamic brakes, and the Frisco and Chicago & North Western ordered units with bigger fuel tanks that required roof-mounted reservoirs.

One thing I did notice in looking at photos was that all of the diesels in this series, and others for that matter, had yellow-painted handrails at the steps. This made stepping onto and off of a moving locomotive a little safer – black handrails against a black locomotive disappear, especially at night.

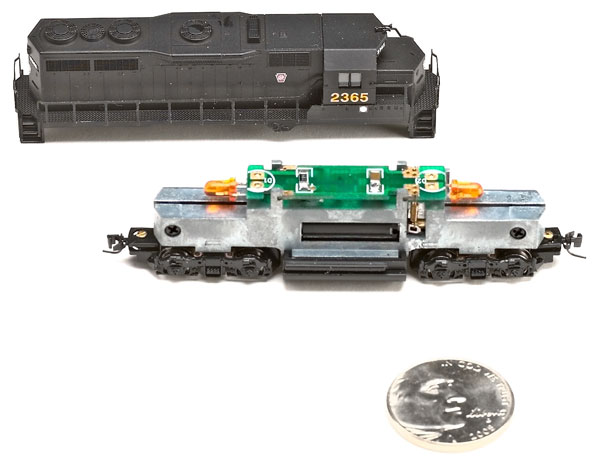

A model this small (about 3″ long and 5 /8″ wide) just begs to be scrutinized. I got out my magnifying glass to look closely at the details – even when I was young my eyes weren’t good enough to see some of what’s on this model. Even under magnification, the handrails retain their good looks. I counted the handrail stanchions – a correct nine, unlike the longer GP40 which has ten, the gentle curve of the handrails at the steps and walkways look right, the walkways themselves have a safety-tread pattern molded in, and grab irons are molded onto the nose and rear; filler caps are also molded in the right places, and the grills have the correct number of vertical supports.

Then I got out the digital calipers and started comparing dimensions against the drawings in the Model Railroader Cyclopedia: Vol. II, Diesel Locomotives. Here are what I consider to be the rather remarkable results: model length over the couplers is a scale 57′-9″ (prototype measures 56′-2″). That’s a discrepancy of 1 percent! Length over the end platforms is 52′-8″ (prototype is 51′-4″), less than 1 percent off. Height is 15′-3″ (the prototype measures 14′-8″). Width is 10′-8″ (prototype is 10′-4″). Those numbers would be pretty remarkable in O or even HO, but this is Z scale. Very impressive.

Enclosed between the weights that take up the entire length of the body are two brass flywheels. On top of the weights is the circuit board, which features directional golden white light-emitting diodes.

The model comes equipped with truck-mounted Magne-Matic Z scale knuckle couplers mounted at the right height (Märklin coupler-equipped versions are also available). Minimum radius for the locomotive is 4½”.

I used the digital calipers again to measure wheel gauge and found all four wheelsets in gauge. Flange depth and tire width are .010″ too wide and deep. These are not RP-25 contour wheels, but the locomotive tracked just fine on our test track.

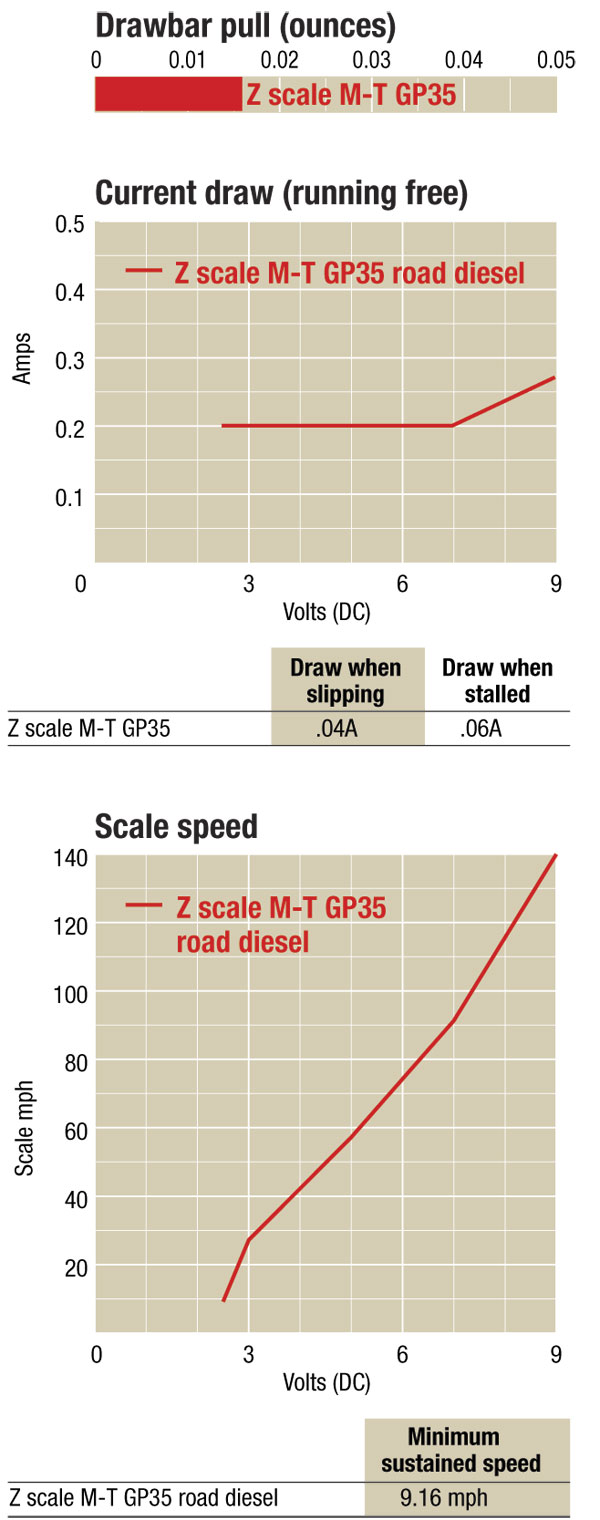

How does all that translate when it comes to performance? Current draw is low, as you might expect. We used an electronic meter to test drawbar pull and barely got it to register at .16 ounce. But, given the light weight and smooth-rolling characteristic of Z scale cars on the market, the little locomotive should pull a train of credible length. We thoroughly cleaned our test track and the locomotive’s wheels prior to testing, and the best minimum speed we could nurse out of her was 16 mph. Top speed is a rather quick 140 mph. That’s fast by prototype standards, but it’s not particularly unusual for models this small.

When I first started modeling in N scale (way too long ago), we didn’t have many choices when it came to locomotives – much less good-looking, good-performing ones. Today it’s a different story, not only in N, but also in Z. It seems to me that Z scale is reaching the point where modelers have a nice choice of locomotives and eras. The Micro-Trains GP35 does a good job of opening railroading in the mid-1960s to Z scale modelers.

Price: Pennsylvania RR (with Magne-Matic couplers) $165.95, (with Märklin couplers) $164.15; Union Pacific $195.95 and $194.15; Canadian Pacific $175.95 and $174.15.

Manufacturer

Micro-Trains Line Co.

P.O. Box 1200

Talent, OR 97540

www.micro-trains.com

Description

Plastic and metal ready-to-run locomotive. Circuit board with terminals for DCC

Road names

Pennsylvania (black), Union Pacific (Armour yellow/Harbor Mist gray), Santa Fe (red and silver warbonnet)

Crisply molded-on details (except horns)

DCC terminals on circuit board

Directional lighting

Dual brass flywheels

Etched-metal handrails

Magne-Matic knuckle couplers (Märklin couplers available)

Minimum radius: 4½”

9-volt coreless motor

Styrene body shell

Split-frame chassis