The prototype. Amtrak began offering passenger service with a hodgepodge of equipment inherited from participating railroads. In the electrified territory, now known as the Northeast Corridor, locomotives were mostly Pennsylvania RR-heritage GG1 electrics. These venerable locomotives were becoming vulnerable as years of wear took their toll.

Amtrak’s first attempt to replace the GG1 was the General Electric E60CP and E60CH, but a derailment at high speed during testing resulted in them being limited to 85 mph in service.

Unsatisfied with this performance, Amtrak imported engines from France and Sweden for testing. The Swedish locomotive impressed the most, and a deal was made to assemble similar locomotives under license in the United States at the Electro-Motive Division La Grange, Ill., plant using components from ASEA of Sweden. The carbodies were built by the Budd Co. in Philadelphia for the first two orders, then Simmering-Graz-Parker in Austria for a third.

The AEM-7 name comes from combining the initials of ASEA, EMD, and 7,000 hp. Railfans came up with their own names for the locomotives – “toasters” for their shape or “meatballs” due to their Swedish heritage.

That horsepower propelled the AEM-7 and about 10 Amfleet cars at 125 mph up and down the Northeast Corridor for nearly 40 years. Amtrak purchased a total of 54 locomotives in its three orders. The first locomotive, no. 900, was delivered in November 1979. The last, no. 953, was built in December 1988. Two locomotives were lost in a wreck in Maryland in January 1986, and fire claimed two more in 2003 and 2011.

Train length was limited not by the locomotives’ pulling power but by their head-end power (HEP) supply. Amtrak rebuilt 29 AEM-7s with AC traction motors starting in 1999. This rebuild also doubled HEP capacity. Around this time, Amtrak installed ditch lights on the locomotives as well, and repainted the engines in the phase 5 scheme.

Other owners were the Maryland State Railroad Administration (MARC), with four, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA), with seven. These locomotives also had Austrian carbodies.

After EMD stopped building AEM-7s, NJ Transit placed an order for the similar ALP-44. These locomotives have larger grills along the roofline and were built in Sweden by ASEA Brown Boveri. NJ Transit owned 15 ALP-44s, which were retired by 2012. SEPTA also purchased a single ALP-44, which is the last of its type in revenue operation.

The Amtrak and MARC fleets have also been retired. SEPTA plans to retire its AEM-7s and ALP-44 as replacement ACS-64s arrive between March and November 2018. Two Amtrak locomotives have been preserved, one at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, Pa., and one at the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Ill.

Roof details are abundant, including metal pantographs that can be used to collect power from overhead catenary. There’s a switch on the motherboard inside the locomotive to select truck or pantograph power.

As these locomotives had long lives, exterior details, especially on the roofs, changed over time. Depicting the prototype from its delivery until the late 1990s, the Atlas model has rooftop equipment similar to, but not exactly the same as, the locomotive shown in the MR drawings. It also has the smooth face of a pre-ditchlight locomotive.

In addition to the rooftop details, the numerous metal grab irons and handrails are separately applied, as are windshield wipers, steps, and placards. The steps to the cab doors are mounted on the trucks to allow for tight model railroad curves, but operators with wider radius curves could pop these off and mount them to the body shell.

The Amtrak phase 3 paint scheme is well done, with sharp separations between the stripes on the sides and the black panels around the windshields and up over the roof. The lettering is crisply printed and conforms well to the corrugations on the model’s sides.

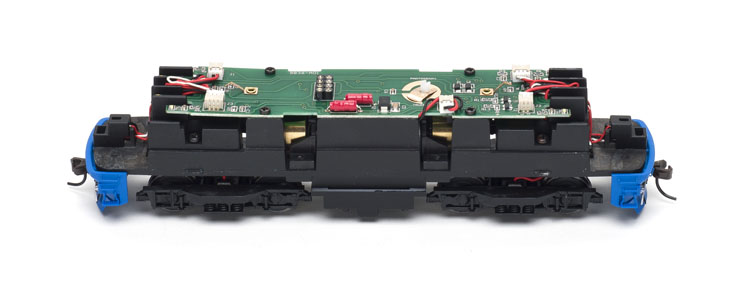

The locomotive’s can motor drives all wheels on both trucks, and all wheels pick up electrical power. Metal weights mounted at each end support a printed-circuit (PC) motherboard over the motor. The ESU LokSound Select dual-mode decoder is plugged into the bottom of the motherboard over the rear truck. A sugarcube speaker is mounted in an enclosure over the front truck.

Surface-mount light-emitting diodes (LEDs) illuminate the number boxes, rooftop strobe lights, headlights and rear marker lights. (AEM-7s were used in push-pull service at times.)

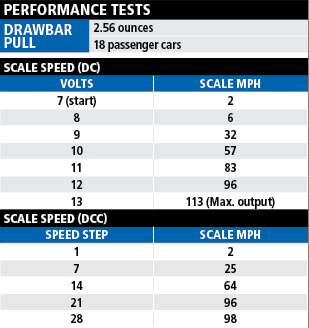

On the test track. I wanted to find out how fast this model ran, as the prototypes were built for speed. At speed step 28 on our NCE PowerCab Digital Command Control (DCC) test setup, our sample reached 98 scale mph. This is a bit short of the top speed of the prototype, but still fast for a model railroad.

In direct-current testing, the model reached 113 scale mph at about 13V, the maximum output of our Model Rectifier Corp. Tech 4 power pack. Further testing in DC revealed a starting voltage of 5.5V for sound, 7V for movement at 2 scale mph. Sounds were automatic, and the lights, including headlights, marker lights, and rooftop strobes, operated depending on direction.

I could control many of these functions independently in DCC. In addition to the lighting functions, the horn and bell sounds can be triggered, a coupler crash on function 3, and HEP fan on F5. This decoder has ESU’s Full Throttle package, so I was able to set and release the independent brake with F10.

The sound package doesn’t make any discernible change as the locomotive accelerates or brakes, except for a brake squeal sound at the end of a quick stop.

I easily changed the decoder address to match the locomotive’s road number, but ESU’s indexed configuration variables (CVs) can make more advanced changes complicated when programming with a DCC throttle. One way around this is to download the free LokProgrammer software from ESU’s website.

Make your intended changes using the menus on your computer, then print out the CV values and enter them manually with your programming throttle. Electronic Solutions Ulm also sells a LokProgrammer interface that allows you to write your changes directly to the locomotive from your computer through a connected section of track. DCC Corner columnist Larry Puckett offers more tips for programming ESU decoders in the May 2018 Model Railroader.

Our pull force meter indicated 2.56 ounces of drawbar pull, equivalent to 36 HO scale freight cars or 18 passenger cars. On our staff layout, the Milwaukee, Racine & Troy, I tested the locomotive with a variety of Amfleet models we’ve collected over the years. Because of the inside-bearing design of the trucks on these cars, they don’t roll very freely, and the locomotive struggled with six cars up a 1.5 percent grade. However, with free-rolling freight cars, the same grade was no problem with 11 cars, and the engine pulled nine cars up our 3 percent stress test grade.

As a fan of Northeastern railroading, it’s good to see these models back in stores after almost 20 years. If you’re hankering to operate passenger trains under wire, either real or simulated, these locomotives could be just the ticket.

$179.95 (DC)

Manufacturer

Atlas Model Railroad Co. Inc.

378 Florence Ave.

Hillside, NJ 07205

www.atlasrr.com

Era: 1980 to early 2000s, as decorated

Roadnames: Amtrak phase 3,

as delivered; Amtrak phase 5; NJ Transit. Fantasy schemes: Milwaukee Road, Pennsylvania RR, and Reading Co.

Also available undecorated

Features:

Accumate knuckle couplers, at correct height

Die-cast metal chassis

Dual flywheels

Full cab interior with painted crew members

Gold version equipped with dual-mode ESU LokSound Select decoder

Operating headlights and marker lights, which are directional

Operating pantographs

Weight: 13 ounces