of detail.

Everything old is new again. Budd’s RDCs were an immediate hit, which seemed to baffle rail watchers of the day. In the few years after the first RDCs hit the rails, Trains magazine (then called Trains & Travel) ran four articles on them, all asking some variation of the question, “Just what are these things?”

After all, as one of the articles observed, self-propelled gas-electric cars – then called “doodlebugs” – had been tried and discarded years earlier as impractical and underpowered. Yet, here was this audacious (and fairly new) car builder, trying to bring the concept back, and improbably succeeding.

The reason for Budd’s success was in part due to its technological innovation, including the company’s “Shotweld” technique for welding stainless steel without damaging its anti-corrosive properties. The car’s performance was also impressive, outpacing the Pennsylvania RR’s M.U. cars in acceleration tests and beating Denver & Rio Grande Western’s California Zephyr on a test run from Denver to Moffat Tunnel.

But the biggest factor in its success may have simply been timing. As automobile sales and highway construction both skyrocketed in the years following World War II, passenger demand on the railroads fell. For many roads, it became too expensive to run a diesel locomotive with only one or two passenger cars in tow. A single Budd RDC-1, on the other hand, could carry 90 passengers and cost about 50 percent less to operate than a locomotive-hauled passenger train.

Between 1949 and 1962, Budd built 398 Rail Diesel Cars, some of which are in revenue operation today. Railroads employed them on branch lines and other little-traveled routes, and in urban commuter service. The cars came in four configurations: the all-passenger RDC-1; the RDC-2, with a baggage compartment and seats for 70; the RDC-3, with 48 seats, a baggage compartment, and a Railway Post Office; and the RDC-4, an RPO-baggage car with no passenger space. Rapido offers HO scale models of the first three. We tested its RDC-1.

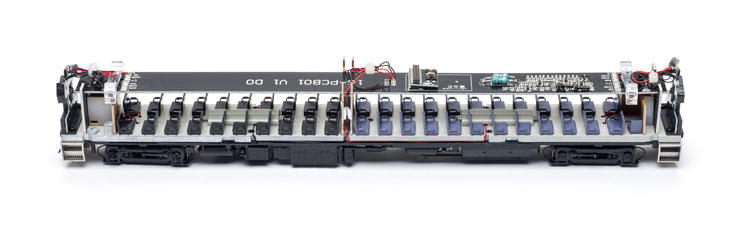

The interior is just as impressive, with constant lighting and painted seats. The twin motors are hidden in enclosures between the rows of seats, below window level, offering an unobstructed view.

The models bear truck sideframes, Gyralights, and other details specific to their prototypes. But to ensure modelers can accurately reproduce every variant of the prototype at any point during its life, Rapido’s RDC includes a sheet of decals and a packet of optional, user-applied details, including a pilot, a pilot cover, window grills, alternate roof grills, exhaust stacks, antennas, horns, diaphragms, and a Gyralite housing.

Model Railroader published drawings of the RDCs in its September 1953 issue. Rapido’s model matched every dimension I measured and checked against that drawing. The model RDC-1 also matched prototype photos in appearance and placement of details.

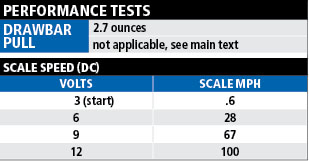

Test run. The prototype RDC wasn’t designed to pull unpowered cars; its couplers were intended solely to link up with other RDCs. Such is the case with Rapido’s version. The manual says that the motors and drivetrain were designed to be small enough to not be visible through the car’s windows, not for power, and that towing another car will void the warranty. Nonetheless, we used our workbench force meter to test the model’s pulling power, and it mustered enough to theoretically pull 19 HO scale passenger cars on straight and level track. Just don’t do so, OK?

Though the RDCs are offered with an ESU LokSound Select sound decoder, our sample RDC-1 is direct-current only. I tested it on our workbench using an MRC Tech 4 power pack.

The car started moving at 3V, rolling at a stately .6 scale mph. (The lights were fairly dim at that voltage.) Though the RDC was famed for its quick acceleration and braking speeds, and would never be caught switching a freight yard, it’s good to know the slow-speed capability is there if you want it. At 12V, the RDC reached a top speed of 100 scale mph, a bit higher than the 87 mph top speed of the prototype. The interior and exterior lights shone brightly at that voltage. The headlights and red marker lights on each end were directional. Rapido’s manual says that working ditch lights are installed, but hidden inside the shell, for the user to mount if his prototype of choice had them.

Since Rapido’s documentation says the RDC can handle a minimum curve radius of 18″, I decided to run the model through the 18″ curves and no. 4 turnouts of our Virginian Ry. project layout. Though it handled the curves and turnouts adequately, the car’s length and overhang caused problems on the layout’s close-quarters tunnels and with trackside details like ground throws and signs along curves. If you’re planning on running this car on tight curves, give it wide clearance. It would look better on broad curves, anyway.

The avenue to better railroading. When Budd’s Rail Diesel Cars came out, they were just what the railroads needed to make branchline passenger and commuter routes profitable again. Since so many hobbyists model transition-era branch lines, with compressed main lines and station platforms, Rapido’s RDCs likewise fill a vital niche.

Trains & Travel justified its unabashed RDC boosterism thusly: “We believe [Budd’s Rail Diesel Car] is one of the brightest, most practical avenues to better railroading. … It is an instance in which we feel objectivity and enthusiasm are not incompatible.” I feel the same about Rapido’s version.

Manufacturer

Rapido Trains

500 Alden Road, Unit 21

Markham, ON L3R 5H5

rapidotrains.com

Era: 1949 to present

Road names: (see website for RDC-1, -2, -3 versions) Canadian National; Alaska RR; Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe; Baltimore & Ohio; Boston & Maine (Minuteman or McGinnis schemes); BC Rail (blue band); Chesapeake & Ohio; Chicago & North Western; Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific; Great Northern; Lehigh Valley; Long Island Rail Road; New York, New Haven & Hartford (script herald or McGinnis scheme); New York Central (early scheme); Northern Pacific; Reading Co.; VIA Rail (original blue-and-yellow stripes and with Rapido decals); and Western Pacific (Zephyrette). Also available painted silver but unlettered.

Features

• 33″ blackened metal wheels, in gauge

• All-wheel drive and electrical pickup

• Detailed and lighted interior

• Dual five-pole, skew-wound motors

• Etched-metal roof grills and fan covers

• Kadee metal knuckle couplers (A end mounted .01″ too low)

• Illuminated number boxes

• Minimum radius: 18″

• Optional user-applied details and decals

• Prototype-specific details

• Separately applied grab irons, door chains, windshield wipers, horns, and underbody details

• Simulated stainless-steel finish

• Weight: 10.8 ounces

• Working nose door Gyralite, where appropriate