Famous as Alleghenies on the Chesapeake & Ohio, Lima-built 2-6-6-6 simple articulated steam locomotives also ran on the Virginian Ry. Rivarossi added a newly tooled tender to its HO scale 2-6-6-6 to more accurately reflect the Virginian Blue Ridge prototype. We reviewed a sample equipped with a dual-mode ESU LokSound V.4 decoder that features chuffing exhaust, whistle, and other sound effects.

The prototype. The Chesapeake &Ohio Ry. received its first class H-8 Allegheny 2-6-6-6 simple-articulated steam locomotives from the Lima Locomotive Works in 1941. The Virginian Ry. received its eight class AG Blue Ridge engines, which were virtual duplicates of the C&O Alleghenies, in 1945. The biggest difference was that the VGN locomotives had larger tenders.

The culmination of Lima’s “Super Power” approach to steam locomotive design, the 2-6-6-6 locomotives were among the heaviest and most powerful ever built. At 45 mph, a 2-6-6-6 produced between 6,700 and 6,900 hp.

On the Virginian, the Blue Ridge engines worked the relatively flat (.20 percent grade) route from Roanoke to Sewall’s Point, Va. A single locomotive could haul 4,500 tons, or about 165 cars, over this route. With dieselization inevitable by the 1950s, the AG class, along with most of the Virginian’s steam power, was retired by 1955. All the Blue Ridge locomotives were scrapped by 1960.

The model. Most of the model’s tooling is based on the C&O Allegheny that was reviewed in the February 2002 Model Railroader. The Rivarossi model measures within scale inches of drawings published in Locomotive Cyclopedia, Vol. 1 (Hundman Publishing).

The plastic boiler features well-defined boiler bands and other molded detail. Factory-installed detail parts include the safety valves, whistle, bell, and locomotive handrails. Other user-installed parts are included, such as the cab and tender handrails, tender to locomotive water connections, and tender truck safety chains.

The Virginian 2-6-6-6 locomotives had smaller two-hatch sand domes than their C&O counterparts. Incorrect for a Blue Ridge, the Rivarossi model has the C&O prototype’s larger sand domes with four hatches.

The newly tooled plastic tender is a highlight for Virginian Blue Ridge fans. The rivet patterns match prototype photos and the dimensions match official Virginian Ry. diagrams.

The color, font, and placement of the lettering match prototype photos. The running board edges and locomotive tires are painted white. The diamond-shaped Lima builder’s plate is legible under magnification and has the correct built date and construction number for no. 900.

The cab interior is painted, including gauges and valves on the backhead. The factory-installed cab has a roof overhang that’s a scale foot shorter than the prototype, which allows the model to round tight-radius curves. A user-installed cab with a scale roof overhang is included, but requires at least 22″ radius curves.

Pulling power and electronics. The mechanism is also the same as recent releases of the Rivarossi Allegheny. A five-pole skew-wound motor with a brass flywheel rests in the center of a die-cast metal frame. Universal shafts connect the motor to gear towers on the front and rear engine.

The blackened metal side rods transferpower to the other drivers. The Baker valve gear is also blackened metal. One prototype discrepancy involves the eccentric cranks, which should lean forward when the crank pin is at bottom dead center. On the model, these parts lean backward at that position.

Both the front and rear engines pivot, which allow the locomotive to negotiate tight 18″ radius curves. However, on the prototype only the front engine pivoted; the rear engine was fixed.

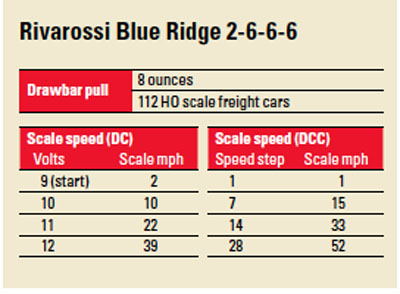

Both the locomotive and tender pick up track power. There are plastic traction tires on one of the rear drivers of each engine. This, and the locomotive’s heft, add up to tractive effort equal to 112 HO scale free-rolling freight cars on straight and level track. Our sample also pulled 20 cars up a 3 percent grade.

The locomotive has a six-wire harness that plugs into a socket on the front of the tender. The socket is wired to the main printed- circuit (PC) board, which is mounted on a die-cast metal weight inside the tender. Our DCC-equipped sample included an ESU LokSound V.4 decoder plugged into the board’s 21-pin socket. A downward-facing speaker is under the weight.

DCC performance. I put the locomotive on our test track and heard the air pump. When I turned on the headlight, the generator came on loudly. Thankfully, it’s easy to adjust the individual volume levels of each sound effect using configuration variables (CVs). A list of commonly used CVs is included with the model. A more extensive guide can be downloaded for free at www.esu.eu/en/downloads/.

As the locomotive moved, I heard the exhaust chuffs, including quick double chuffs that simulated the independently operating engines of the prototype simple articulated going in and out of step with each other.

Out of the box, the chuffs were out of synch with the drivers. I used CVs 57 and 58 to adjust the synchronization so that when the engines were in step, the chuffs were the correct four chuffs per wheel revolution. Like other models that don’t use a mechanical cam to synch the chuffs, the synchronization wasn’t perfect at all speeds.

The whistle has the deep steamboat quality of the prototype. Other user-triggered functions include the bell, coupler, and safety valves. Function 9 triggers radio communication, which is anachronistic. All of the function buttons can be remapped, so it’s easy enough to disable this effect.

The ESU decoder provided smooth motor control right out of the box. At 28 speed steps, the locomotive crept along at 1 scale mile per hour. At speed step 28 the locomotive attained 52 scale mph, which is close to the prototype’s 60 mph top speed. After setting the steps to 128 and adding acceleration and deceleration momentum, the locomotive looked and sounded even more realistic as it hauled a coal train on our layout.

DC performance. Like most sound-decoder- equipped locomotives, the ESU-equipped Blue Ridge required a lot of voltage to get started. The model moved at 9 volts, holding a steady 2 scale mph, and accelerated to a prototypical service speed of 39 scale mph at 12 volts.

The sound effects are limited when using a DC power pack. As I advanced the throttle the exhaust chuffs increased, but they weren’t in synch with the drivers. With a quick reduction of the throttle, I heard squealing brakes. I also heard other random sounds, such as the air pump. A DC sound controller, such as an MRC Tech 6, would allow access to most of the sound effects on a DC layout.

Rivarossi’s 2-6-6-6 was an impressive model back in 2002, and is even more so with the addition of an ESU LokSound decoder. The accurate tender should please Virginian fans looking for a Blue Ridge to haul hoppers to tidewater on an HO layout.

Manufacturer

Rivarossi

Distributed by Hornby America

3900-C2 Industry Drive East

Fife, WA 98424

Era: 1945 to 1955

Road numbers: 900 (DCC), 907 (DC)

Features

▪▪ESU LokSound V4.0 dual-mode sound decoder (DCC version)▪▪Five-pole skew-wound motor

▪▪Light-emitting diode (LED) headlight and backup light

▪▪Plastic knuckle coupler on rear oftender, at the correct height

▪▪RP-25 contour metal wheels, in gauge

▪▪User-installed pilot knuckle coupler

▪▪Weight: 1 pound, 13.3 ounces (engine and tender); 1 pound 6.7 ounces (engine alone)