One of the largest and most powerful steam locomotives ever built is now available in HO scale equipped with a top-of-the-line Digital Command Control sound decoder. Just like the prototype, Rivarossi’s HO scale Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy” is well equipped to pull long freight drags up and over the mountain ranges.

This isn’t a new model; Rivarossi has used versions of this tooling for close to 50 years now. Dana Kawala reviewed a version of this locomotive in our July 2009 issue. What’s new in this release is the upgraded ESU LokSound Digital Command Control sound decoder.

A born mountain climber. The Union Pacific designed the Big Boys with builder Alco for one purpose: to conquer the 1.14 percent ruling grade of UP’s line through the Wasatch Mountains east of Ogden, Utah, without need for helper locomotives. Furthermore, to obviate power changes, the new engine had to be able to pull its freight trains at high speed once past the mountains. In fact, the 4-8-8-4 design was originally supposed to be named the “Wasatch.” But during construction, an Alco worker chalked the words “Big Boy” on the smokebox of one of the first engines, and the moniker stuck.

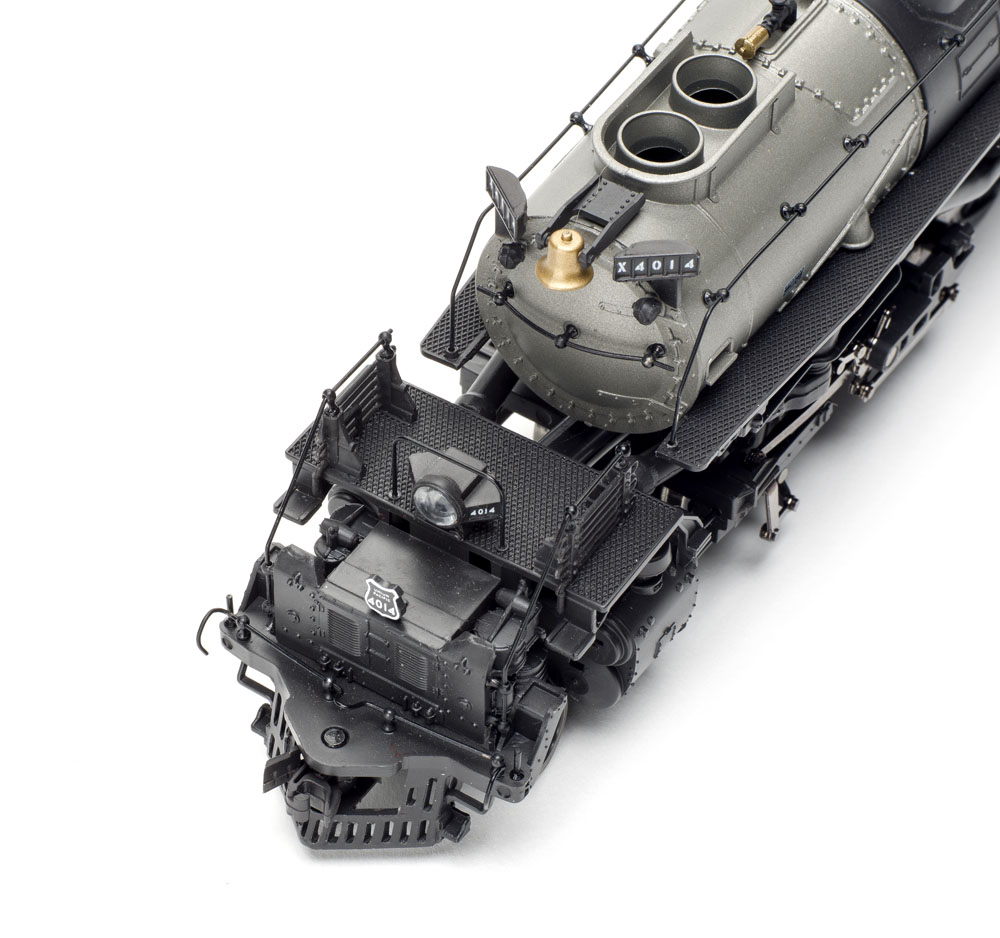

Union Pacific bought 25 of the Big Boys – two batches of 10 in 1941 and another group of five in 1944. They were numbered from 4000 to 4024. Rivarossi’s models are numbered 4014 and 4018, both from the second 1941 order. Both are among the nine Big Boys that still exist today. 4018 is on display at the Museum of the American Railroad in Frisco, Texas, and 4014 is undergoing restoration to running condition at the Union Pacific’s shops in Cheyenne, Wyo.

The models have vertically mounted air-cooling pipes on either side of the pilot deck, a hallmark of early Big Boys.

The model. Like UP’s earlier 4-6-6-4 Challenger, the Big Boy was articulated to help it negotiate curves and turnouts. On the prototype, the front engine pivoted under the smokebox. On the model, both engines pivot, which is necessary to handle 18″ radius curves, but it creates unrealistic cab overhang. The leading and trailing trucks “float” on springs to further improve the locomotive’s handling on curves. The tender’s lead truck and rear axle do the same.

All 16 drivers are powered, and all have flanges; the wheels rely on side play to let them take sharp curves and turnouts. Electrical pickup is via seven of the eight drive axles, as the third wheelset is equipped with traction tires. There’s no electrical pickup on the tender.

The locomotive is painted a smooth satin black, with graphite smokebox and firebox. The white lettering is opaque and matches prototype photos. The tiny lettering under the cab number is legible under magnification, as are the builder’s plates on the smokebox.

The major dimensions of the locomotive matched drawings in Model Railroader Cyclopedia: Vol. 1, Steam Locomotives (Kalmbach Publishing, 1960). The drive train is slightly different, though, to allow the locomotive to handle 18″ radius curves. The wheelbase is stretched by about a scale foot to allow more swing room between the two sets of drivers. Also, the prototype Big Boy has 68″ drivers; in order to maintain prototypical axle spacing while accommodating the model’s deeper flanges, the model’s drivers are 64 scale inches.

For the most part, the tender matches the dimensions in the Cyclopedia, as well. The exception is the width; while the prototype is 10′-10″ at its widest point, the model is 4 scale inches wider. This difference isn’t apparent to the eye.

The tender is equipped with a magnetic knuckle coupler on the back. According to our gauge, it drooped about .040″ low, which could easily be solved with a shim in the draft gear box. Like the prototype, the model was equipped with a swing-out coupler on the pilot. This was a dummy on our model, but since the Big Boy wasn’t intended for double-heading, it’s preferable to a working but oversized coupler.

Testing. The locomotive performed admirably under direct current. When the voltage reached 7V, the headlight came to life, along with the whine of its dynamo. Air pumps and water injectors sounded randomly as the engine sat idle.

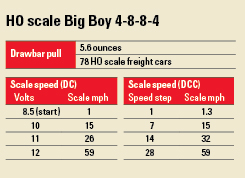

As I increased the voltage to 8.5V, the engine started to creep forward at 1 scale mph, neither stuttering nor hesitating. The locomotive performed smoothly through its voltage range, reaching a top speed of 59 scale mph at peak voltage.

Though you can’t trigger the bell or whistle in direct-current operation, the ambient sound effects are well done. The exhaust sound features the correct four chuffs per wheel revolution and the sounds of the two engines realistically go in and out of sync while the locomotive is moving. Reversing the direction switch on the power pack triggers the clank of a Johnson bar. Rapidly slowing the locomotive elicits the squeal of brake shoes on steel wheels.

Under Digital Command Control, the user has more control of the sound effects. Function key F1 triggers the bell, F2 and F5 play long and short horn sounds respectively, and F3 plays a coupler clank. Other function keys trigger other sounds; a full list is in the manual, downloadable from www.esu.eu/en/.

The locomotive’s speed range in DCC operation is similar to that under DC. Speed step 1 set the engine rolling at 1.3 scale mph, and at speed step 28, it topped out at 59 scale mph. Setting the throttle to 128 speed steps resulted in much finer speed control.

The model is designed to transit 18″ curves. The drawbar has three holes to let the user choose how close to couple the engine to the tender. The closest spacing gives the most prototypical appearance, but requires the widest curves. I used the end hole, giving the widest gap, when testing the engine on the 19″ curves of our Eagle Mountain project railroad. Though the large overhang of the smokebox and cab on curves caused problems with adjacent structures and scenery on our layout, the locomotive had no trouble staying on track on the curves or turnouts.

The Big Boy sure looked better on the broader curves of our Milwaukee, Racine & Troy layout, though. On that layout, the model easily pulled a 15-car train up a 3 percent grade. I was pleased to hear the chuffs fade as it topped the grade and started to drift downhill.

Our test bench force meter showed a pulling power almost as impressive as the prototype’s. The weight of the engine and the traction tires combined to give a drawbar pull of 5.6 ounces, enough to pull 78 standard 40-foot free-rolling boxcars on straight and level track.

Impressive. Rivarossi’s 4-8-8-4 Big Boy has been around a long time, but with its fine wire details, smooth performance, and updated sound decoder, this is definitely a modern scale locomotive. Hobbyists modeling the Union Pacific’s steam era shouldn’t need a reason to want one (or more) of these brawny beauties in their roundhouses.

Price: $459.99 (with DCC and sound), $389.99 (direct-current, no sound)

Manufacturer

Hornby Hobbies

3900-C2 Industry Drive E

Fife, WA 98424

www.hornby.com

Era: 1941 to 1959

Road numbers: 4014 and 4018

Features

▪▪Blackened metal wheels, in gauge

▪▪Can motor with dual flywheels

▪▪Directional light-emitting-diode (LED) lighting

▪▪Eight drive axles

▪▪Electrical pickup on seven driver axles (traction tires on both drivers of third drive axle)

▪▪ESU LokSound Select sound decoder (DCC version)

▪▪Magnetic knuckle coupler on tender; swing-out dummy coupler on pilot

▪▪Weight: 1 lb., 10.6 ounces (engine alone: 1 lb., 2.6 ounces)