Prior to World War I, steam locomotives were built in small lots by numerous builders working to individual roads’ specifications. There was no such thing as a standard design.

But when America entered World War I in 1917, the railroads weren’t up to the task of moving all the men and

materiel needed for the war. In response, President Woodrow Wilson formed the United States Railroad Administration (USRA) and nationalized the railroads.

One of the railroads’ biggest problems was a shortage of locomotives. The USRA proposed to have a large number of new steam engines built to a set of standard designs. These designs were huge successes. Railroads continued to buy USRA engines long after the war ended and the railroads returned to

private control.

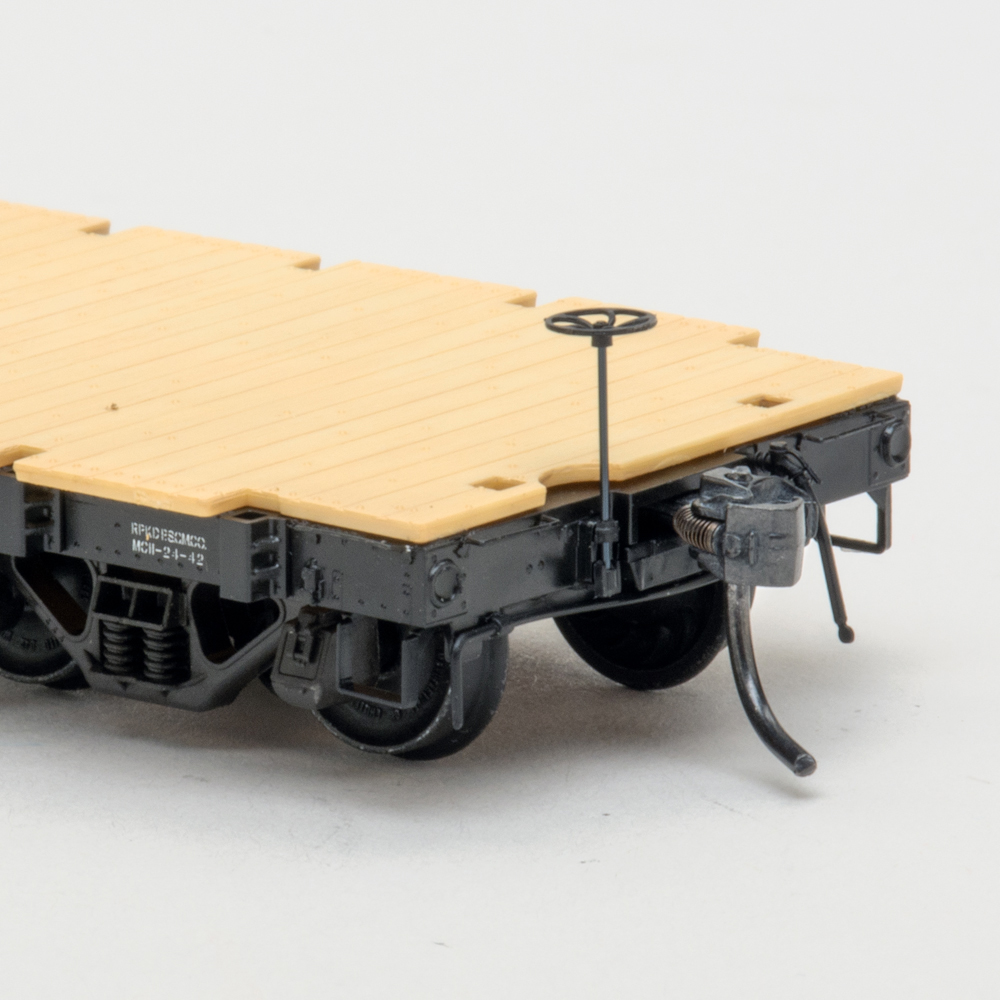

The boiler bristles with accurate details. Grab irons and uncoupling levers are wire, and the abundant pipes, sand lines, and other fittings are flexible engineering plastic. The pilot and tender are fitted with metal knuckle couplers, mounted at the correct height.

The cab is detailed with wire grab irons at the corners and an optional removable cab curtain. The cab windows slide open. A cab apron extends backward to the tender’s deck. Crew figures aren’t included.

The engine’s plastic body is smoothly painted black, with a graphite smokebox. The white printing on the cab and tender was sharp, straight, and opaque, and matched the New York Central’s post-1936 lettering. The smallest print in the builder’s plates on the smokebox were legible under magnification.

Under the engine’s plastic shell, a can motor with dual brass flywheels is housed within a hefty cast-metal frame. A worm gear transmits power to the rear drivers, which are equipped with a set of traction tires. The side rods transfer motion to the other three axles.

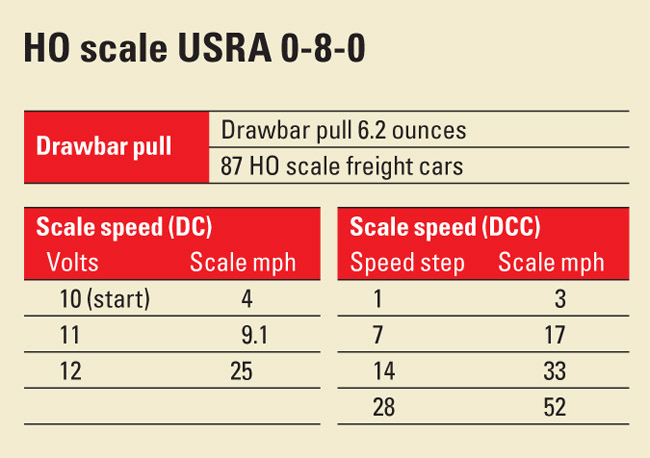

As is typical for sound-decoder- equipped locomotives, it takes a lot of voltage to get things going. Ambient sounds, such as the air pumps, started at 6V. As I advanced the throttle, the locomotive started moving smoothly at 10V.

The engine is geared for low-speed operations, perfect for a switcher. It started out at 4.2 scale mph at 10V, and reached a top speed of almost 25 scale mph at 12V. (If you have access to a DCC system, lowering the value programmed into Configuration Variable (CV) 63 – Analog Starting Voltage – will start the engine at a lower voltage under DC.)

When it starts moving under DC, the locomotive whistle toots twice as the engine starts forward and three times as it moves backward. To be prototypical, whistle signals should happen before the locomotive starts moving. The exhaust is correctly timed to four chuffs per driver revolution. The Johnson bar clanks when the direction is reversed.

Under DC, the user can trigger an grade-crossing whistle sequence by rapidly turning up the throttle and a brake squeal by quickly turning it down. The light-emitting-diode headlight and backup light are directional.

The user has more control over the sound effects in DCC mode. For example, function 4 plays a steam release sound, and F11 triggers a brake squeal. You can hear the dynamo whine when the lights are turned on.

I tested the locomotive with an NCE Power Cab. The engine responded smoothly to speed step 1, rolling at 3 scale mph. At speed step 28, it topped out at 52 mph.

Changing the decoder’s address was a simple task. I also tested all possible values of configuration variable (CV) 115, which selects the steam whistle sound. Sixteen whistles are available.

Drawbar testing. A six-pin plug under the locomotive cab apron fits into a socket on the front of the tender. In addition to connecting the electronics, this part also functions as a drawbar between the locomotive and tender. During our drawbar testing with a stationary force meter, the engine would pull loose from the tender. However, this wasn’t an issue during real-world testing.

On our club layout, the Milwaukee, Racine & Troy, I tested the locomotive’s pulling power with an extreme hill climb. The 0-8-0 hauled 20 cars up a 3 percent grade without slipping, stalling, or unfastening from the tender. Needless to say this yard goat has plenty of power for its normal flat switching duties.

A ubiquitous switcher. The 0-8-0 switcher was the most numerous USRA-designed locomotive. North American railroads rostered 1,375 USRA 0-8-0s and copies. These doughty yard goats stayed on duty switching and making transfer runs for Class 1 railroads until the last days of steam. The new model from WalthersProto would look right at home working any HO scale classification yard set in the last decades of steam.

Manufacturer

Wm. K. Walthers Inc.

P.O. Box 3039

Milwaukee, Wi 53201

www.walthers.com

Era: September 1918 to early 1960s (1936 to early 1950s as detailed and decorated)

Road names: New York Central; Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; Erie; Nickel Plate; Northern Pacific; and Southern (two road numbers each).

Features

- Blackened metal National Model Railroad Association RP-25 contour wheelsets, in gauge

- Dimmable, reversing light-

- emitting-diode (LED) lights

- Electrical pickup on four drivers and all tender wheels

- Proto MAX metal knuckle couplers at correct height

- Plastic body and tender shell

- Sliding cab windows

- SoundTraxx Tsunami DCC sound decoder (optional)

- Three-axle electrical pickup

- Traction tires on rear drivers

- Weight: 9.5 ounces (engine alone), 13.5 ounces (engine and tender)

- Wire grab irons and uncoupling levers