My wife and I had just returned from a trip to Norway to see the homeland of my ancestors and renew the acquaintance of a couple of Norwegian model railroading friends. After 28 years of work at Kalmbach Publishing Co. as – at various times – Model Railroader’s copy editor and managing editor, editor of Classic Toy Trains, and editor-in-chief of Kalmbach Books, the Norway trip was a post-retirement treat Diana and I had planned for several years. But now we were back home and had both slipped into retirement pretty comfortably. Then the phone rang.

Model Railroader’s managing editor, David Popp, and editor, Neil Besougloff, made a proposal. They wondered if I’d be interested in building an N scale project railroad for the magazine. The parameters were broad, the deadlines reasonable, and the compensation was within the guidelines of what one on Social Security can receive. So after consulting with Diana, I agreed.

Here was the guidance I got from MR: The N scale layout needed to feature modern-era Western railroading, preferably feature Digital Command Control (DCC), and use Kato’s new Unitrack with superelevated curves. It also had to be portable, roughly 4 x 8 feet, and be aimed at those in the beginner-to-intermediate skill level.

Most of these criteria left me little wiggle room: N scale (standard gauge), DCC (brand left up to me), Kato’s superelevated curved track (thus mainline railroading), portable (lightweight materials), and skill level (I consider my skills intermediate, at best). There were two elements that would require more thought and decision-making.

Modern era in the West

I suppose I could have chosen one of the smaller regional lines, but wanting to stick with mostly ready-to-run equipment, that meant BNSF Ry. or Union Pacific. Burlington Northern took over the Santa Fe (one of my favorite railroads, and I bear a bit of a grudge), so I zeroed in on the UP.

But where along the UP? Wyoming, though a beautiful state, really doesn’t offer a lot of dramatic scenery. Northern Utah and northern California? Maybe, though the Feather River Canyon has certainly been modeled many times before. Southern California? Mojave Desert, Sullivan’s Curve, Cajon Pass – also pretty well represented by layouts in all scales.

In the back of my mind, I recalled John Signor’s book, The Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad Company: Union Pacific’s Historic Salt Lake Route. Originally published in 1977, by 2008 it no longer covered the modern era (and most, if not all, of the photos were black and white).

During a conversation with Matt VanHattem, senior editor at Trains magazine, he asked if I’d seen Mark Hemphill’s well illustrated and comprehensive book, Union Pacific Salt Lake Route (Boston Mills Press, 1995).

It was exactly what I needed. Beautiful color photographs taken along the entire line from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City; a well-written and detailed description of the line; and maps that include elevations, grades, and mileposts. The text describes in detail the history of the line from its inception in 1900 as the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake RR (soon dropping the San Pedro and becoming the LA&SL) to its publication-date status as the South Central District of the UP (the “Salt Lake Route”).

Rugged mountain desert scenery

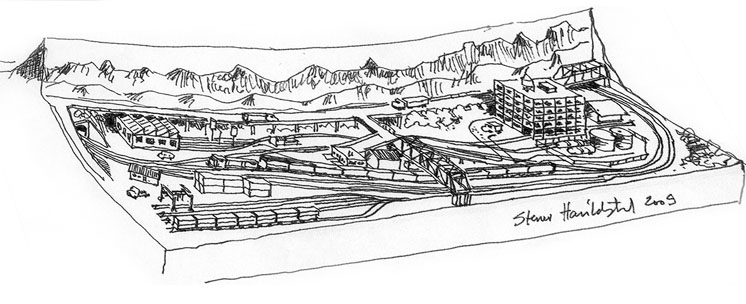

Salt Lake City is 784 miles (via the UP) from Los Angeles, and the layout MR wanted was to be roughly 4 x 8 feet. So, which scale half-mile should I build? For several hours I paged through the book, front to back and back to front. There was plenty to choose from. I envisioned the layout would in some way be divided into parts, probably by a backdrop down the middle, so that meant two scenes. One should probably represent either desert or mountain scenery (maybe both); the other should be somewhat more urban, including an industry or two for switching and a yard of some sort – an intermodal yard would be interesting and appropriate.

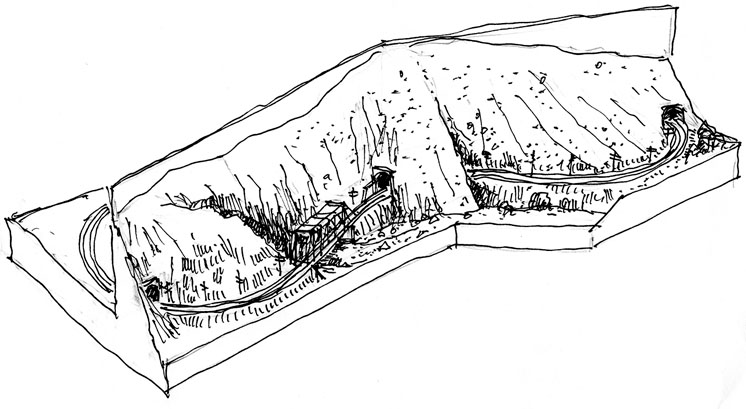

At this point two photos on facing pages of the Salt Lake book caught my attention. The first (top), by Keith Ardinger, shows a UP extra struggling up the 1.5-percent grade west of Stine, Nev. The other photo (bottom), by Jamie Schmid, features a pair of big UP locomotives hauling a long string of auto racks through tunnels 7 and 8 east of Stine. The scenery is quite different even though the two photos were taken only a few miles apart. Keith’s picture includes a small stream, known as Meadow Valley Wash, in the foreground. The stream leads your eye into the photo where the train crosses silver steel truss bridges over the stream. To the left the track disappears between sheer, rocky canyon walls. Very dramatic. Perfect for an N scale layout.

Jamie’s photo also includes the wash, running parallel to the main line, which cuts through the base of two smallish hills. The tunnel portals aren’t far apart, allowing a long train to be in two tunnels at one time. And the scenery appeared to be easy to model: sand, some rock outcroppings, tunnel portals, and small shrubs – millions of small shrubs!

While poring over the photos, I realized that if I carefully rolled the two facing pages together, the two photos became one. Amazingly, I’d found the subject of one side of the layout on facing pages in a book.

Caliente industrial area

I hoped that I could find similar inspiration in other photos for the Caliente, Nev., side of the layout. No such luck. Elements of several photos provided inspiration, but nothing like the mountain photos. That being the case, I let available structure kits determine what would appear on the other side. One key element would be the intermodal yard; for that, I’d need a Walthers Mi-Jack Translift intermodal crane kit (933-3222) and some sort of office for the yard.

Engine servicing ought to be available also. The Walthers car shop (933-3228) is good-sized, has an interesting roofline, and looked like it would be easy and fun to build. Most of us have more locomotives than we have main line, so this would also be a good spot to store a couple extra engines. A sanding tower would add interest and be appropriate for mountain railroading.

At the other end on the layout, I needed an industry or two. The Walthers Hardwood Furniture Factory kit (933-3232) has covered loading docks – an interesting feature. Another possible industry to include would be the Walthers Interstate Fuel & Oil (933-3200).

Finally, a small, modern yard office along the main line wouldn’t look out of place. With that somewhere near the middle of the layout, the space would be pretty well filled.

As far as track goes, the mountain side would make use of the Kato Unitrack with superelevated curves in an S configuration, with a couple straight sections here and there. On the real line through the narrow canyons, most of the right-of-way is single-track (though many of the tunnels had at one point been modified to accommodate two tracks). I suspended disbelief on the basis of modeler’s license. Besides, a double-track main line would allow the MR staff to run trains in circles in opposite directions for display at train shows and other events.

Track configuration on the Caliente side was more problematic, but I’ll get into that later in this series. Essentially, though, I needed at least part of an intermodal yard, an engine-servicing area, passing sidings, and a few industries served by rail.

I was given the option of using flextrack on the yard side to join the ends of the Kato section from the mountain side. However, I liked the ease of using the Kato Unitrack with its attached roadbed, so I worked with it throughout. Determining which sections to use proved to be a challenge, but in the end all of the track snapped together perfectly, and the trains run reliably. I believe I chose wisely.

Perfect railroad for the hobby

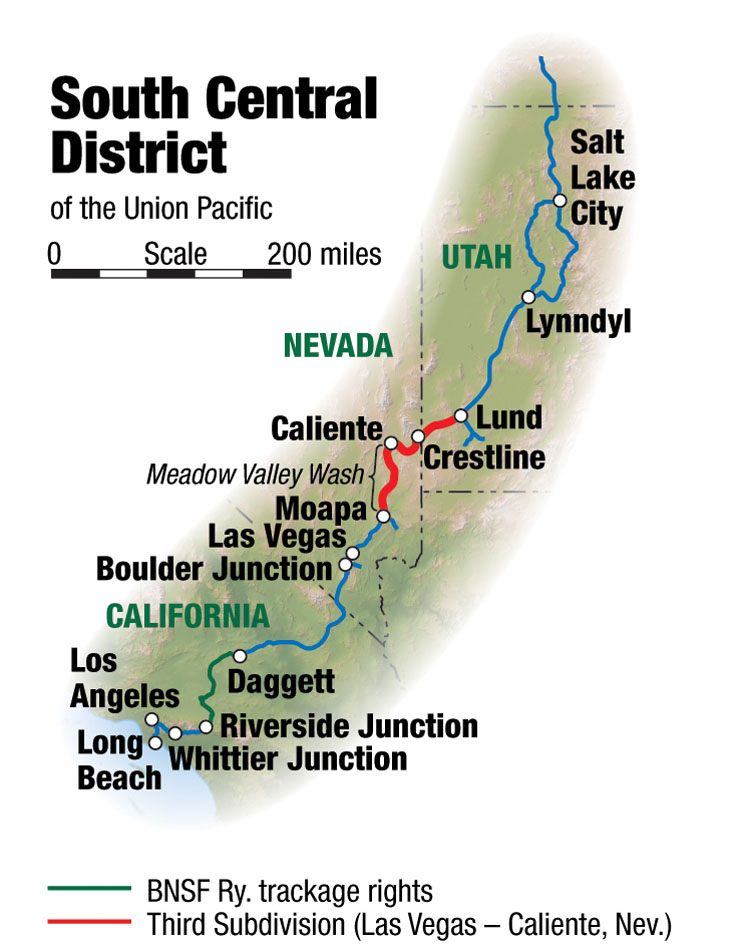

The Third Subdivision of the South Central District runs from Moapa, Nev., at milepost 383.1 and an elevation of 1,663 feet above sea level, to Crestline, Nev., at milepost 495.7 and 5,902 feet [See map. – Ed.] So, in 110 miles the line climbs 4,239 feet. The grade between those two points varies between 1.00 and 2.06 percent. Over that same stretch the line passes through 15 tunnels and weaves back and forth across Meadow Valley Creek on a couple dozen steel bridges. The curves are many, and they’re tight. It’s a railroad built for modeling!

From Moapa to Caliente, the railroad climbs eastbound through the area known as Meadow Valley Wash. The rest of the trip to the summit at Crestline follows Clover Creek Canyon.Stine, near the locations represented on the mountain side of the layout, is at 4,049 feet.

Meadow Valley Wash is generally dry, though occasional heavy rains can catch the unsuspecting railfan midstream. The line today is several feet higher in most places than it was in 1910 when a flood wiped out much of the railroad, carrying ties into the Colorado River and burying rails under as much as nine feet of silt. At considerable expense, the Los Angeles & Salt Lake realigned track, bored new tunnels, and raised the line along the sides of canyon walls to where it is today. In some places the location of the old roadbed is still visible – obviously much too close to the level of the creek!

Rail traffic through the Wash

Over the years, rail traffic has been what you’d typically expect: produce and livestock from California headed east, strings of tank cars from the California oil fields, auto racks from the Midwest bound for the West Coast for sale or export, and piggyback trains in both directions. Some of Union Pacific’s signature name trains, including City of St. Louis, Challenger, City of Los Angeles, and Pacific Limited, also plied these rails.

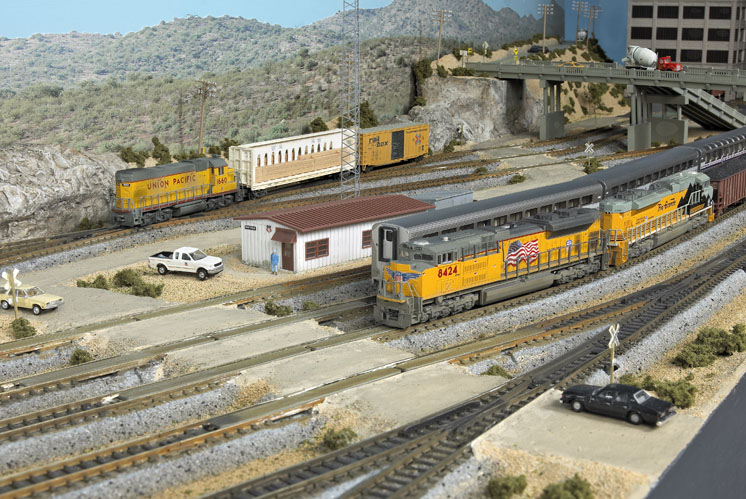

Today, no passenger trains growl through the canyons, though you could certainly make up a story that would permit Amtrak to run to Los Angeles via Salt Lake City and Las Vegas and vice versa. In terms of freight traffic, though, the first thing you’ll notice is that it takes a lot of locomotives to manage these grades. The UP runs long trains over the mountains, and it takes an enormous amount of horsepower to get the freight out of the desert and onto the gentle grades of the Great Plains.

Rolling along behind those six-axle Armour Yellow locomotives today are loads typical of big-time mainline rail- roading: coil steel cars; a variety of covered hoppers filled with grain, fertilizer, soda ash, and cement; loads of coking coal; and lumber from the Pacific Northwest. Unit coal trains for export to Asia and container trains from the Port of Los Angeles heading east are by far the most common types of traffic seen on the Salt Lake Route.

Layout preview

This isn’t an especially difficult layout to build. It’s small enough that it won’t take you forever to finish it; the Caliente side of the track plan could be simplified, though as it is, it’s not too complex; wiring for Digital Command Control is about as easy as it gets; and the scenery is simple – sand, some rockwork, and bushes (did I mention that there are lots of bushes?). That’s about it.

Over the years, traffic has varied enough that almost any cars or locomotives would be appropriate. And if you don’t care for the Union Pacific, freelance it and make it your own favorite railroad.

As for operation, the main line is simply two loops with a crossover at one end of the yard. You could run trains east and west in continuous loops while you switch a container train. You could also have a locomotive make up a cut of cars leaving the furniture factory (or bringing in raw materials). If you wanted to, you could run a helper operation out of the engine-servicing tracks, pushing a train up the canyon at one end and then cutting off and returning to the engine tracks when the train comes back around from the other end.

On the mountain side, because of the steep grades, trains headed eastbound work hard and grind along at minimum speeds. Though the model railroad as shown here is level, you can suggest that eastbound trains are working hard by running them slowly. Trains headed in the opposite direction (westbound and downgrade) could run somewhat faster, suggesting an easier trip, but they’d still be using dynamic brakes on the downgrade. Because of the tight curves, you’d hear flanges squealing – fun to simulate if your modern diesel locomotive is sound-equipped with that feature.

The railroad step by step

Part of my agreement with Model Railroader was that I would photograph construction of the layout. In fact, I shot more than 600 photos. The subsequent articles won’t include all of them, but there will be plenty of photos so you can get a clear idea of the process. If the modern Union Pacific Salt Lake Route doesn’t inspire you, the layout could easily be backdated to the steam-to-diesel transition era. You could turn the intermodal yard into a set of team tracks or add a freight house. Hopefully you’ll follow along and apply some of what you learn to a model railroad of your own choice.