CHICAGO — J.D. Danton’s shift at Metra’s 16th Street Tower on Friday night and Saturday morning (April 11-12, 2025) was certainly nothing new. And yet, the dilapidated structure had never seen anything like it — and never will again.

Danton was the operator on duty when the interlocking tower dating to 1901 relinquished its control over the diamond crossing of Metra’s Rock Island District and Canadian National’s St. Charles Air Line. The interlocking is now operated from Metra’s Consolidated Control Facility, little more than 3,000 feet away on the opposite side of the Chicago River at 15th and Canal streets.

The latest deletion from the ever-dwindling number of operating U.S. towers leaves Metra with just three:

— A2, at the complex, busy junction of tracks from Metra’s North and West districts and Union Pacific’s main line (for Metra, the UP West route) to reach Union Station and the Ogilvie Transportation Center;

— B17 in Bensenville, Ill., where the Milwaukee West route meets the connection from a UP line that brings CPKC traffic into Bensenville Yard.

— Lake Street Tower, which controls access to the Ogilvie Transportation Center, the terminal for Metra’s UP (ex-Chicago & North Western) lines. That tower also remotely operates what used to be operated from Clinton Street Tower.

The cutover to remote operation was slated to continue through Monday — and some work will go on for months as temporary measures are replaced by permanent changes. Operators were scheduled to remain on duty for at least another day as a backup.

But essentially, the handover from the tower to the CCF about 3 a.m. Saturday marks the end of operation of a structure that has been in service for more than half of the history of American railroading, noted Tom Hunter, chief signal engineer for contractor Modern Railway Systems.

Danton understood the significance of the moment.

“Clerks have worked in this tower seven days a week, 24 hours a day, for 123 years,” he said. “Even if the trains weren’t running … we were still here, because this is our home. So it’s a little melancholy.”

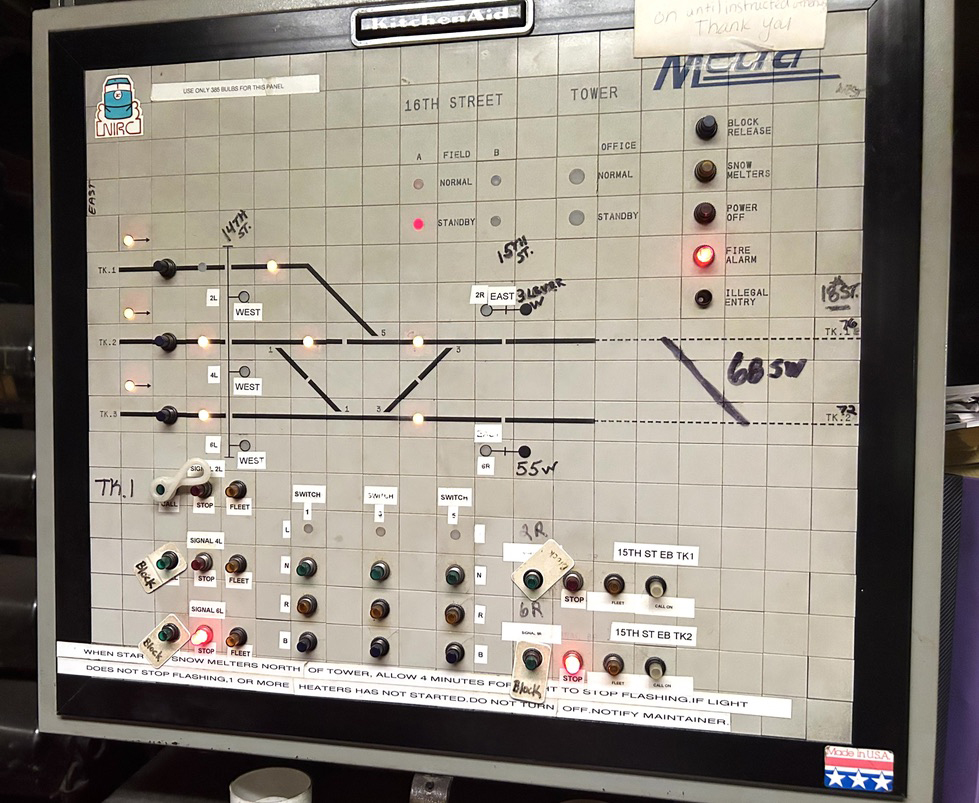

Earlier in the evening,operator Wanda Rivera had been the last to line signals for a train — Metra Rock Island train No. 511 to Joliet, which left LaSalle Street station at 8:25 p.m. and passed by the tower at 8:30 p.m. Within five minutes, wiring to the signals had been cut to be rewired for the remote operation — “There go my track circuits,” Rivera said, looking at the lights on the tower’s model board. From then until the handoff to the CCF, Rivera and Danton spent the night talking trains past the inoperable signals — which mostly still glowed red but occasionally were dark altogether.

The video below shows what it was like as Danton, who took over from Rivera a little after 10:30 p.m., talked the next-to-last outbound Metra train of the night, a scheduled 10:45 p.m. departure from LaSalle Street, past one set of the out-of-service signals about 10:54 p.m.

Rivera — who, like Danton, had come to Metra from CN and had been working at the tower for five years — called the night “bittersweet.

“People are afraid of changes,” she said. “And I’m one of those people. I could do this in my sleep. … But on to new things.” Rivera plans to train to become a dispatcher.

While the tower at its closure handled a relatively simple junction, as shown by the model board at right, that was certainly not the case in its early days, as attested to by the more than 100 levers that operators once had to manipulate, and the maze of wires and relays on the tower’s first floor.

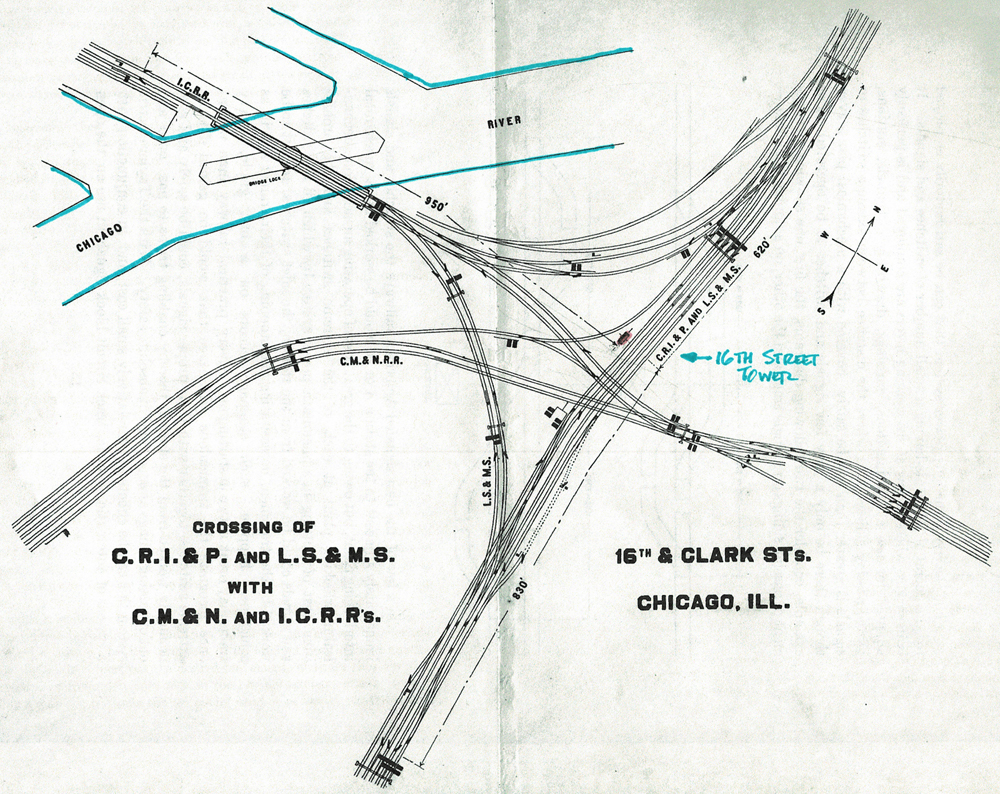

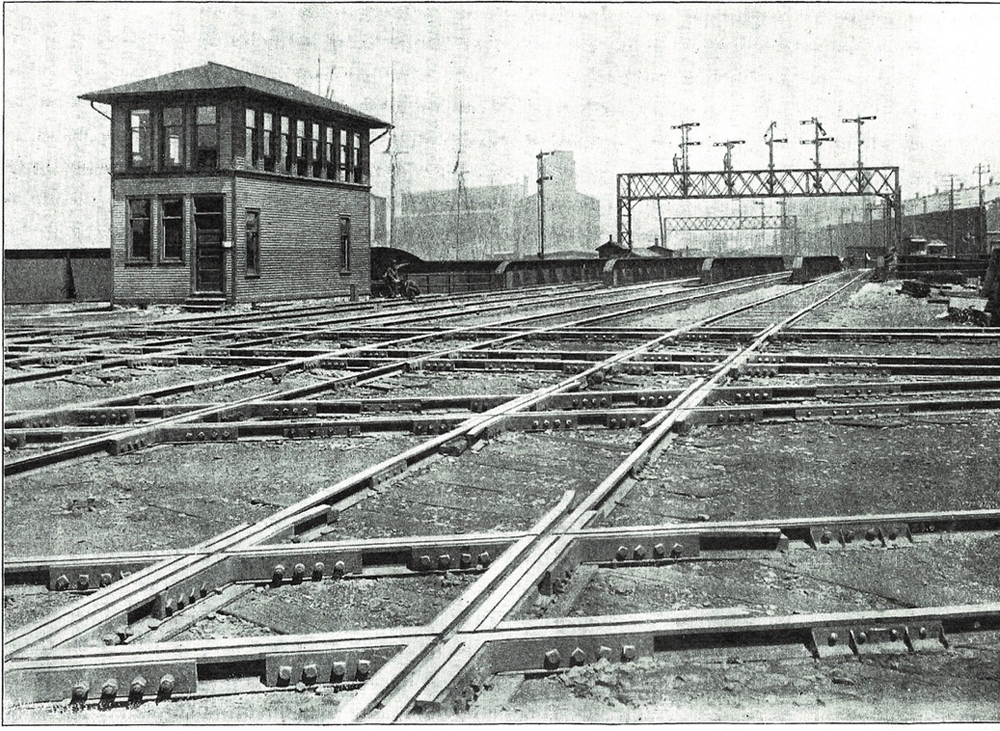

The then-new tower is featured in a 1902 catalog of the Taylor Signal Co. (“Manufacturer of the Electric Interlocking System,” the catalog’s over proclaims). That catalog includes this diagram of the site (the tower location is highlighted). Not only has the track plan become dramatically simpler, but the Chicago River (also highlighted) was rerouted by the city of Chicago and now runs more parallel to the Rock Island tracks.

The tower today looks little like the image from that catalog (below). Virtually all of the windows visible here on the upper floor have been covered over; that door and windows on the first floor are also gone. Visibility is now so restricted that when Rivera was talking trains through on Friday night, she had to leave her desk, go down the outside stairway on the side away from the tracks, and walk to the end of the building to make sure the previous train had physically cleared the diamond.

The building today looks fairly rickety, and to some extent, that’s true. Rivera said that on particularly windy days, “you’re actually rocking back and forth. I’m like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ You actually get nauseous. It’s crazy.”

But there are some enormous wooden beams on the first floor that help keep it together, and it stands on a foundation far newer than the rest of the structure. The Chicago Transit Authority’s subway Red Line passes immediately beneath the building, and Red Line work led to the tower being jacked up and placed on a new, sturdier concrete base. You can, however, clearly hear every Red Line train that passes below.

But there are some enormous wooden beams on the first floor that help keep it together, and it stands on a foundation far newer than the rest of the structure. The Chicago Transit Authority’s subway Red Line passes immediately beneath the building, and Red Line work led to the tower being jacked up and placed on a new, sturdier concrete base. You can, however, clearly hear every Red Line train that passes below.

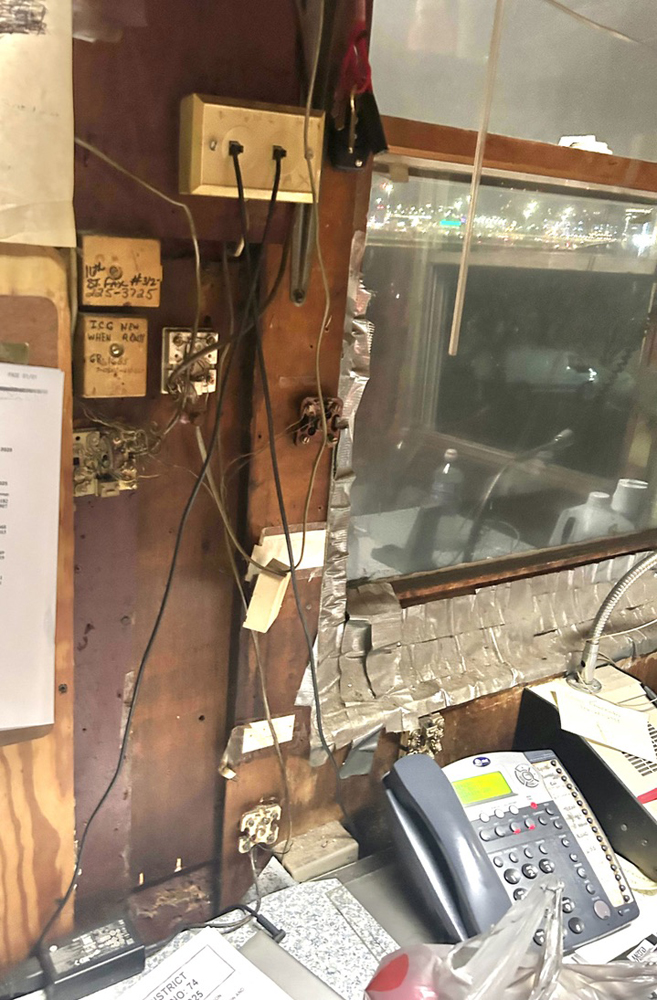

From a technical standpoint, it was, at the end, a virtual museum of technology as much as a working railroad facility. Danton pointed out a spot next to the desk that is a collection of phone jacks and other wiring that bears testimony to, as he put it, 60 years of communication technology. (There were also traces of the former telegraph lines if you knew where to look, he said, but they were not readily apparent).

And the first floor is a maze of relays and wiring. Most date to the era of the more complicated layout and are completely superfluous. But as Tim Pitzen, Metra senior roadway engineer, pointed out, why risk taking anything out and disturbing the ancient equipment that still does its job?

To squeeze through the stacks of relays and wiring is also to get a sense of the human history of the structure. Various signal maintainers have quite literally left their mark on the building, carving messages into the wood that supports the relays and other electrical gear.

Metra has designs on donating the interlocking machinery to a museum. While the entire structure deserves to be preserved, it would be physically impossible to relocate it — not only because of its condition, but because it is too tall to be transported under the bridges it would encounter in any relocation effort.

So, at some point, it will come down. For the time being, though, it will continue to stand guard over the tracks it has protected for more than a century.

For the first time, though, it will do so without human occupants. The rodents that have coexisted with them will, for the time being, have the run of the place.

— Updated April 14 at 8:41 a.m. to correct number of active Metra towers, adding Lake Street Tower.

I would hope that IRM can get ahold of those relay boxes and telegraph breadboards. They can build a duplicate of the tower building as it was in 19xx.

And as for the cable holding the building together, they are probably right. That is why the building sways in the wind, its taking up slack in the cables.

Remember that before its final closure, the historic wooden tower accommodated an average of 120 Metra moves per day, along with 10 CN trains.

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

We want the railroad to live… that’s why it must evolve because evolution is life!

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

I don’t believe we’ve recently heard from Mark Shapp (did I get his name right?) the retired METRA tower operator who moved to Pittsfield Massachusetts.

For dispatching my favorite is A2 on the Milwaukee. All that traffic (and the extreme skew) yet I’ve never been delayed either on Amtrak or Metra Milwaukee North or Metra Milwaukee West or UP Metra West.

A2 was (no longer, the grain mill has been demolished) where you’d be most surprised to see a Norfolk Southern switcher. This grain traffic was a holdover from when PRR served both the north and the south tracks at Union Station.

My favorite for the physical scene is West Detroit (if it still exists — it’s been many years). Coming in from Ann Arbor at night, the light in the tower’s windows, it just looks so much like a big-time railroad scene you want to see.

The Junction does, and was upgraded many years ago by Amtrak and CSAO for faster speeds onto the Michigan Line.

BRADEN — Is the big tower at West Detroit still there?

Towers I have been in back in the day when the doors were unlocked:

Delray (Detroit, Michigan) c. 1976

Livernois Hump (Detroit, Michigan) c. 1975

Dolton (Illinois) c. 1990 but was politely asked to leave

No it was demolished years ago.

Speaking of Delray. CSX owns the tower. It was closed in 2020. I imagine it’s days are numbered.

This tower could be physically preserved. Example: VN tower in Nova, Ohio, was relocated to Heber Valley RR in Utah. The structure was disassembled and its pieces numbered for future reassembly.